This policy note was prepared for a report published by The Islamabad Policy Institute (IPI) after the general elections of 2018.

As the previous government completed its tenure, its relationship with the military establishment had considerably deteriorated. It would require a fresh effort on the part of both the incoming civilian government and the military leadership to rebuild a relationship of mutual workability, trust and cooperation. This is perhaps the most vital condition for the continuation of democratic transition, as well as informed and accountable policymaking in the country.

The new civilian government that assumes power in 2018 will face a plethora of challenges, on both the external and the internal fronts. India’s hostile approach towards Pakistan will not abate anytime soon, and the country’s new foreign minister will have the unenviable task of balancing Pakistan’s fraternity with China, with improving relations with New Delhi and its new strategic ally United States of America.

Relations with Afghanistan, meanwhile, continue to remain dogged by a lack of trust and by issues such as the presence of Pakistani Taliban on Afghan soil, fencing the Durand line, among others. These problems will unfortunately persist in the new government’s tenure as well. The new government must aim to achieve cordial relations with Afghanistan, without compromising on Pakistan’s internal security, and on its desire for a peaceful settlement in Kabul.

Pakistan’s internal landscape too is beleaguered by multiple challenges. Quetta’s precarious security situation will continue to pose a major challenge to the government that comes to power in 2018, with the low grade insurgency continuing in Balochistan risking the timely completion of projects under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Although Pakistan has substantially overcome the menace of terrorism, the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) has highlighted the need to re-build and develop the country’s war-torn regions.

Violent sectarianism is another obstacle the new government will have to overcome. The recent rise of a militant strand of the Barelvi movement has exacerbated sectarianism, and further polarized the Pakistani society. Many radical outfits have made inroads into Pakistan’s democratic structures – especially the political parties –and if this is not checked, a radical and myopic narrative will come to dominate public discourse in the country.

The list of security challenges is long and handling it would require a collaborative vision, effective coordination between the civil and military branches of the government. Most importantly, it would require that the ruling party and its cabinet views the military not as an intrusive entity but a vital arm of policymaking and government operations. Similarly, it would also require a fresh start on part of the military commanders recognizing that the constitutional scheme of governance has an inherent logic, disruption of which is not in national interest. This will not happen anytime soon but if the two sides are willing to engage and place the country’s welfare above the narrow confines of institutional interests, Pakistan could move towards an equilibrium of sorts.

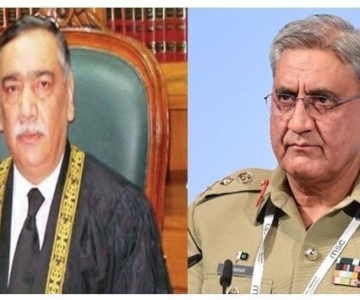

In this context, the new civilian government will have the uphill task of dealing with the aftermath of former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s conflict with the Army.

Moving beyond Sharif-military duel

In May 2018, former Prime Minister (PM) Nawaz Sharif leveled serious allegations on the military and intelligence agencies. He alleged that he was ousted due to his decision to push Gen Musharraf’s treason trial. The succession of events since then, according to Sharif, were steered by the military to destabilize his government to the extent that he was ostensibly sent a message by an intelligence agency head to resign during the 2014 protests. In May, Sharif’s interview with Dawn created another rupture wherein he told the newspaper, “Militant organizations are active. Call them non-state actors, should we allow them to cross the border and kill 150 people in Mumbai? Explain it to me. Why can’t we complete the trial?”

This was a reference to the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks. New Delhi has always accused Pakistan’s military and intelligence agencies of having a hand in the incident, something that both the military and the civilian government have always denied. Nawaz pushed the military establishment in the international spotlight in his attempt to fight back against the ‘Khalai Makhlooq’ or the hidden hands he believes were behind his ouster from the PM’s office.

As expected, the Indian media voraciously jumped on this juicy new story. A three-time PM of Pakistan had accused the Pakistani military of indirect involvement in an act of international terrorism. It is easy to understand the infuriated reaction of the country’s military leadership. Also, in May 2018, a National Security Council (NSC) meeting, called to address this issue, declared Nawaz’s statement as ‘incorrect and misleading’. Sharif did not budge, embarrassing his own colleagues and continued with his narrative.

History of Civil Military relations

It is well-known that Pakistan’s political history is tainted by a civil-military paradigm heavily skewed in favor of the military. The reasons behind this imbalance go all the way back to 1947 and to the unique environment in which the Pakistani state was born. Emerging from a Muslim nationalism that gripped the subcontinent in the late nineteenth century, Pakistan came into being with its two wings separated by a thousand miles of ‘enemy’ Indian territory. Existential fears, therefore, played on the minds of Pakistan’s founders since its inception and necessitated the diversion of most of the country’s resources towards the military.

The army thus benefitted from state patronage that was unavailable to the country’s underdeveloped civilian structure. Moreover, the American largesse that the military enjoyed because of Pakistan’s decision to side with the US in the Cold War facilitated the growth of the army that then developed at a pace that far outstripped Pakistan’s struggling democratic landscape.

The inability of political parties, especially the Muslim League, to develop a strong grassroots following in Pakistan coupled with the incessant squabbling that came to define Pakistan’s democracy in its first decade, led to popular support shifting towards the ‘only professional and competent’ institution in Pakistan—the military. This imbalance eventually culminated in Pakistan’s first-ever military coup of 7thOctober, 1958, when Pakistan’s then President Iskander Mirza abrogated Pakistan’s constitution and declared martial law in the country.

Periods of military rules spread over decades led Pakistan’s Army to view itself as the final arbiter of “national interest.” The military gave itself a preponderant role in state affairs, while it continues to exercise veto power over the nation’s security, foreign, and economic policies.

1971 marked a historic moment in Pakistan’s history, not only because East Pakistan had seceded and formed the independent country of Bangladesh, but also because Pakistan’s military was at a historic nadir in terms of public support and influence. Pakistan’s new Chief Martial Law Administrator (CMLA) and the kingpin of the party that had received the most votes in West Pakistan in the 1970 elections, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, thus had the perfect chance to cement democratic control in the new and truncated country.

Although Bhutto did give Pakistan its constitution in 1973, he resorted to authoritarian rule that once again damaged democracy and led to the army regaining its lost prestige. The straw that broke the camel’s back, however, was Bhutto’s decision to rig the 1977 elections, which again enabled the military to intervene once again in Pakistan’s politics. Thus, Zia-ul-Haq launched ‘Operation Fairplay’ on 5thJuly, 1977 that overthrew the Bhutto regime and installed yet another military ruler at the helm.

Pakistan’s military establishment has played a dominant role in Pakistan since the 1977 coup. In addition to the eleven years of direct, draconian rule under the Zia regime, the establishment continued to indirectly influence the political process, especially elections during the tumultuous 1990s. This included the ‘Mehran Bank’ scandal of the early 1990s, as well as the political maneuvering that led to Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s resignation in 1993.

The country once again faced the specter of direct military rule when Pervez Musharraf overthrew the democratically elected government on 12th October 1999. He reigned until 2008, a period that coincided with Pakistan’s involvement in the War on Terror and one that was marked by rapid economic growth.

Since 2008 democracy has returned to Pakistan but the military’s direct and indirect role in governance and policymaking continues to dominate Pakistan’s political landscape. Through the past decade, the military has dominated conversation on important topics such as foreign policy and the overseeing of military operations against radical outfits. At present, the military has left the formal seat of power, but its control over crucial policy domains continues to undermine the authority of civilian governments.

The military in short remains an alternate and autonomous center of influence and power on issues related to state affairs such as national security, foreign policy, internal security and counterterrorism. This autonomy of the military influences the consolidation of democratic order in Pakistan.

Civil Military relations (2008-2018)

Pervez Musharraf’s downfall in 2008 paved the way for democratic transition in Pakistan, and following the outpour of support for the judiciary, it seemed democracy was once again back on track. The decade following Musharraf’s ouster is, thus, a good period to assess how Pakistan’s civil-military relationship developed and where this relationship now stands.

The PPP’s tenure from 2008-2013 was marked by a turbulent civil-military relationship. While the Asif Ali Zardari-led government achieved some remarkable democratic achievements, such as becoming the first democratically elected government to complete its tenure, passing the eighteenth amendment, and issuing the National Finance Commission (NFC) award, its relationship with the military was thorny at best.

Several factors contributed to this turbulent relationship. The military continued to assert its dominance first by ensuring then Army Chief Ashfaq Kayani gained an extension to his tenure, and then by undertaking military operations against militants on its own terms. These operations did not forage into North Waziristan, which subsequently led to the global community, and especially Washington accusing Pakistan of not taking on the Haqqani network, and thus being disingenuous in its attempt to quash militancy.

Tensions, however, reached their acme in 2011 when the ‘Memogate Scandal’ rocked Pakistan’s political landscape. Following the American raid in Abbottabad that killed Osama bin Laden (OBL) on the 2nd of May 2011, Pakistani businessman Mansoor Ijaz revealed that then Pakistan’s Ambassador to the US, Hussain Haqqani had allegedly approached him with a memo that asked the American government to intervene and protect Pakistan’s democratic regime given the risk of a coup.

The memo highlighted the rift between the civilian government and the military in the fallout of the American raid and asserted that a military coup was imminent in Pakistan. Ambassador Haqqani subsequently resigned, and the Supreme Court is still to conclude the matter.

The scandal in fact highlighted that Pakistan’s civilian government was still unable to assert itself on the military. Differences in the response to the raid against OBL, moreover, showed the government and the military’s inability to see eye to eye on security and foreign policies. This tension would spillover to Nawaz Sharif’s government that took the helm in 2013, with civilian and military institutions clashing over relations with India and over the military operations taking place in the country.

The PMLN years (2013-2018)

Civil-military tensions started to plummet when the PMLN government under Nawaz Sharif initiated a special court to try former President Pervez Musharraf for treason. A three-judge bench indicted the former army chief in March of 2014 for abrogating Pakistan’s constitution and for declaring an emergency in 2007.Fundamentally, it reflected a desire by the civilians to hold the military accountable and this trial was very symbolic, because Musharraf had violated the constitution not once but twice. Army leadership reportedly resented the Musharraf case because the military could not see its chief be tried for treason and be punished particularly, as it was going to affect the morale of the armed forces. Nawaz Sharif understood this and despite warnings pursued the case to keep the military in check. There was a personal score to settle as well since Musharraf had ousted and exiled Sharif.

The fall-out from the trial, and the behind-the-scenes maneuvering to extricate Musharraf from facing charges highlighted that the civilian government and the establishment were heading towards a confrontation. This inability to be on the same page spilled over onto other policy domains as well, especially with respect to relations with India and Afghanistan, and in the military operation against the Taliban the country launched in June 2014. Musharraf, meanwhile, managed to avoid charges against him, and ended up leaving the country reportedly for health treatment abroad.

PML-N was well aware of the animosity that existed between Nawaz Sharif and the military. Sharif was pressured to abandon his office in 1993by the armed forces. In 1999, he tried to remove General Pervez Musharraf as Chief of Army Staff for the Kargil debacle. This attempt backfired and resulted in a coup d’état and Sharif was jailed and later exiled. His last stint in office was marred by civil-military tensions throughout. Pakistan People’s Party (PPP)that assumed power three times was no stranger to this phenomenon.

Sharif’s government was destablized with three rounds of ‘dharna’ (sit-in) led by Imran Khan who reportedly enjoys the support of sections within the security establishment. Sharif as archrival of Benazir Bhutto in the 1980s and 1990s played a similar role and therefore the historic trend has continued.

Delaying action against militants for political/strategic gains: Another strain in the civil-military relations during Nawaz Sharif’s tenure was that he delayed giving the go-ahead for a full-fledged military operation in Punjab after the launch of Zarb-e-Azb. Eventually, an operation had to be launched after the March 2016 terror attack in Gulshan-i-Iqbal park in Lahore.

Reportedly, the PML-N leadership had been delaying the launch of an operation because they feared the political backlash of such an endeavor, and they were also politically dependent on some of the groups being targeted. This led to tensions between the military and Nawaz because here he became an obstacle between the military and the consolidation of the gains they had made against terrorists in operations in other parts of the country.

Foreign & Security policies: Based on the experience of the past decade, the civilian government and the military have come to loggerheads over certain specific issues. These are foreign policy endeavors– particularly when it comes to India and Afghanistan – military operations within Pakistani territory and to deal with the non-state actors active in the region. In fact, the latter issue is what the infamous Dawn leaks – which initiated the degradation of the incumbent government’s relationship with armed forces – was all about. Apparently, Nawaz Sharif, who was still PM back then, had beseeched the military leadership to abandon its ‘good and bad terrorist’ policy because it was isolating Pakistan on the world stage. When the contents of the meeting were reported, civil-military relations took a nosedive.

Military’s permanent interests

A unique element of Pakistan’s military lies in the fact that it possesses extensive business and corporate interests throughout the country. In 2016, for instance, then Defence Minister Khawaja Asif revealed to Parliament that there were around 50 entities that were run by the military. These include the Fauji Foundation, the Shaheen and Bahria Foundations, the Army Welfare Trust (AWT) and the Defence Housing Authorities (DHA). The army also runs several insurance and welfare trust organizations that allow it to provide social security to its retired personnel.

Researchers have argued that the military requires direct access to Pakistan’s corridors of power primarily because it wishes to protect and enhance its business interests. The total (now dated) estimate of the military’s commercial holdings is around US$20 billion. The military’s ability to augment its corporate resources, moreover, stems from its ability to provide welfare to the millions who join the armed forces, and because of the army’s narrative that it is a better manager of organizations vis-à-vis civilian organizations and the public sector. Following the models of East Asian countries, this needs to be regulated and should become the basis for a civil-military dialogue.

The structural issues are not going to change but an environment of mutual mistrust and imbalance needs to be rectified.

Rebalancing power

With the general elections just around the corner, it is important for the winning party to be on the same page with military establishment while forming the government at the center. What makes the situation somewhat problematic is the de facto involvement of the military in state affairs. Armed forces, according to the Constitution, report to the elected executive. But this has never really been the case in Pakistan.

If continued unaltered, this pattern is harmful for Pakistan’s international standing as a sovereign country and its struggling democracy at the national level. Nawaz Sharif, despite all his faults, had a valid point in arguing that “you cannot run a country with two or three parallel governments”.

To fix the structural civil-military imbalance, the first and the foremost change must come from the country’s political elite itself. They must stop using the military against one another to improve their own chances of forming the central government. Throughout the 1990s the PML-N and PPP ruthlessly used the military establishment against one another. Eventually, the leadership of both parties was forced into exile. The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) and its chairman, Imran Khan, would do well to learn from history here, as they have used the same tactics since the 2013 general elections.

The political elite must also make more of an effort to make a meaningful connection with their constituents. It will be more difficult for the military to have a role outside constitutional/legal boundaries if the country’s citizens are politically astute and significantly consider the power of their votes. When the political elite fails to do this, it becomes easier for the military to steer its narrative of an insecure polity cursed by corrupt politicians necessitating a supra constitutional involvement in national affairs that ranges from de facto control of policy making to direct takeover.

The Way Forward

It is absolutely essential that both the civilian and the military establishment adopt a paradigm that brings harmony to Pakistan’s politics. For this to happen, however, both sides must take concrete measures that can uphold civilian supremacy, and through which they can respect each other’s mandates.

The first step in this regard should be to activate and strengthen the National Security Council (NSC) that has remained, on balance, moribund since 2009. The government must appoint a NSC adviser, and ensure that the forum serves as a platform where civilian and military leaders can engage in constructive and open debate. The NSC must also be the first avenue where both sides can make recourse when an issue arises, and both the civilian and the military sides must eschew talking to the media on critical questions without first discussing matters in the NSC.

Tensions, however, will not subside without civilian governments strengthening Parliament. It has become commonplace for elected governments to circumvent parliament on key issues, which has only eroded trust and faith in democratic institutions. This tendency must be jettisoned and instead, the government must activate committees in both houses that focus on, and deliberate important matters of national security. This will lead to more parliamentary oversight on security-related matters and will also lead to a more informed debate in parliament on issues that plague the civil-military relationship. This must then be followed by think tanks operating in the Senate and in the National Assembly that can help parliamentarians by releasing reports and publishing articles on problems in Pakistan’s economic and security paradigms.

Pakistan’s state institutions must also realize that it is only through working together that they can rid the country of the seemingly intractable problems it faces. Thus, it is absolutely essential that the civilian governme

nt, the judiciary and the armed forces sit together on the same platform and chalk-out ways that bring harmony in the trilateral relationship. Former Senate Chairman Raza Rabbani, in fact, suggested this very idea, and it is important that other leaders pick up this suggestion. A lot of problems in the turbulent civil-military relationship stem from poor communication and a lack of trust, which makes it all the more necessary that the three pillars of the state come together.

The Ministry of Defense and the armed forces must also develop better means of disseminating information. The present system of the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) and the Ministry giving separate press releases too often leads to contradicting statements and it highlights a lack of coordination between the civilian and military wings. This has also often exacerbated tensions with the ISPR claiming one thing, while the civilian side argued another.

The military on its part, must bring greater transparency in the military operations it is conducting. This is essential to build trust between civil and military institutions. While a civil-led and owned operation against militants will strengthen Pakistan’s global standing, and also bring credibility to its claims of eradicating terrorism. This will naturally involve a reduced role for paramilitary troops in guaranteeing security in urban areas such as Quetta and Karachi, and even in FATA.

For it remains a fact that the security challenges present in these areas are the result of poor political decisions, and it is only a healthy political process that can end the violence which plagues these places. Thus, civilian oversight is essential to ameliorate the security concerns that exist in Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the rest of the country.

Both the executive and the military need to abandon all ties with extremist groups, and the NAP needs to be fully implemented. It is high time to realize that militias pose a threat to Pakistani and foreign citizens, and the Pakistani military and civilian leaderships’ alliances with them in the past have only been damaging for the country. Not only will implementing NAP make Pakistan safer, it will also bring the executive and the military on the same page.

In short, the specific proposals are as follows:

- Activate NSC and don’t make it a hub of competition and conflict

- Activate parliamentary committees on national security

- Hire defence sector professionals in Ministry of Defence and empower it as the civilian voice on defence issues

- Enable Minister of Defence in management and policy affairs of three services

- Introduce a parliamentary committee on Intelligence. DG-ISI should regularly brief parliamentary committees

- Set up think tanks within Senate and NA that assist legislators with issue briefs and create informed debate

- Build capacity within political parties for tackling defence, security issues and foreign policy

- Military should value civilian input into security policy (on non-state actors, trade with India, etc.)