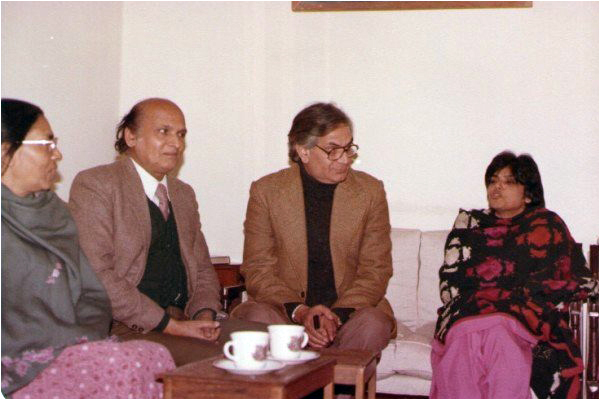

I remember the languid afternoon in Lahore when I met Intizar Husain surrounded by his friends and admirers. This formal introduction happened as poet-writer Fahmida Riaz was visiting Lahore and wanted to see Intizar Sahib as we all called him. This was nearly a decade ago and my memory of that meeting is a bit hazy. All I remember is that Intizar Sahib showed extraordinary enthusiasm when he heard my name.

Arrey I have been reading you in The Friday Times, he said. Bewildered, I thought that he was trying to humour a young novice with literary pretensions. Noticing my maladroit attempt to hide my expression, he added in chaste, homely Urdu: I had thought that this guy Rumi was some old man writing about the shared cultures of the subcontinent. Aap tau naujawan nikle (you turned out to be a youth).

In those days, I was regular feature writer at TFT and had penned many a rant on the civilisational ethos of the Indian Subcontinent that has fast eroded in the past few decades. Little did I know that it would be noted by of all the readers Urdu’s master fiction writer and columnist, essayist and a critic!

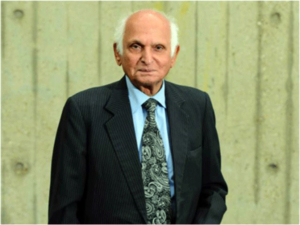

Intizar Sahib had resisted the temptations of turning into a cult figure, a pop star or a pir

This was a moment of reckoning for me. I was but a pygmy in front of this literary giant and man of all proverbial seasons. Hearing his acknowledgment was a kind of homecoming a process that continues, distracted by the necessities of garnering jobs and nurturing pretenses of a career. Among other reasons to change direction in my life, perhaps Intizar Sahib was a major reason. His encouragement to an utterly unimaginative person like me acted as an elixir.

This meeting was the first in which I managed to speak to Intizar Sahib. One had seen him for years at various events in Lahore. Unlike the other senior writers, Intizar Sahib had resisted the temptations of turning into a cult figure, a pop star or a pir. We have had many a celebrated writer turning into feudal patriarchs and patrons. This is not an exaggeration. Former bureaucrat-turned-writer and also the architect of censorship under Ayub regime (1958-1968) Qudratullah Shahab was declared as a mystic pir by his groupies; and for some time his formal urs (commemoration) celebrations were also held. Perhaps these still continue. I have lost track.

For the next few years, I met him as regularly as possible. Every Sunday, Intizar Sahib was found with Eruj Mubarak, Khaled Ahmed, Zahid Dar, Gulnaz and Zaman Khan among others. I would join them occasionally as I shuttled between Lahore and Islamabad for work. These were soirees that shall never be equaled. Intizar Sahib listened quietly, interjecting here and there. Seldom did he attempt to assert his seniority or the wealth of knowledge.

On many occasions, I witnessed a most rare, civilised discourse on language between Khaled Ahmed and Intizar Sahib. Khaled Ahmed’s thesis that Urdu had been appropriated by the extremists and therefore become a vehicle of retrogressive ideas was politely challenged by Intizar Sahib, who always maintained that Urdu was a vibrant language in both Pakistan and India. Such discussions in the age of TV talk shows and abusive social media interactions appeared as a leaf from a fading world of ideational exchange.

When I was working on my book Delhi by Heart, it was Intizar Sahib’s world that had inspired me. In his travelogue Zamin Aur Falak Aur (A Different Land, A Different Sky), he writes:

Dear traveler, do not waste your journey because of your mental reservations. Keep your heart open when you go travelling and leave unfastened the windows of your mind. Every habitation has its own atmosphere and its special fragrance. No town is devoid of evil men, nor empty of good ones. And every journey has its own sufferings and its own delights. For all this, it is meant that the traveler keeps himself open. Out of this very all this comes the special fragrance of his journey. (translation by Safdar Mir)

I did not consciously follow this advice but having read this while I was still in high school, these lines stayed with me. It was only in recent years when I picked up the book after two decades, I realised that Intizar Sahib’s fascination for the peacock near Nizamuddin Dargah and its voice representing the spirit of Delhi that had lost its way in the bushes around was calling out to the lost ones. For Intizar Sahib this had to do with physical separation from the soil but for my generation it was the delinking and a conclusive one at that from a civilisation. It was about a thousand years past rubbed into dust of jingoism.

When I told him about my book and its obsessions, Intizar Sahib was delighted. He was also the first one to read it and review it for Dawn. He sensed that I had unwittingly treaded his path: Rumi feels that he is moving in a vast world which carries a touch of the divine, where the past and the present merge into each other and the Hindu-Muslim divide loses its edge. For a beginner, this was nothing less than a windfall, a memory I cannot cherish enough.

From 2010 to 2014, I attended the Karachi Literature Festival (KLF) and in the initial years, I had the privilege of interviewing him as well as participating in several panels where Intizar Sahib held forth. I travelled with him to India for a Manto conference and another event during these years as well. In a session with him, he spoke of his early memories and the writing process. He also made the famous statement that he had seen two [paradoxical] forces rise in Pakistan: the power of the mullah and that of women.

Averse to being didactic or patronising, Intizar Sahib was always eager to listen. Curious about what I did other than my work for TFT, he had a list of questions. It was a little difficult to speak to him on the telephone as he had become hard of hearing, so our conversations would almost always take place in person. When I took translator and noted author Rakhshanda Jalil to his house, Intizar Sahib was more than hospitable. Our meeting was extended by hours and as we sat in his bedroom that had books everywhere, I realised how his writing was his life. So whenever I would ask Intezar Sahib about his writing schedule and techniques, he would laugh and say it was a perennial part of his existence.

Intizar Sahib was different from most of the luminaries of Lahore’s literati for a host of reasons, foremost being his status as an outsider. He moved from the United Provinces (UP) of undivided India to Pakistan and landed in Lahore. The city, its physical and cultural environs became his new home. As the certainty of Partition became clear and an iron curtain between India and Pakistan was erected after the 1965 war, the new home could only be imagined with the memory of what was left behind. This is why hijrat or migration became a perennial theme of his fiction.

When India carried out nuclear tests in 1998, a key concern for Intizar Sahib was the fate of peacocks in Rajasthan

As time flew in the new Muslim homeland, the theme became sharper and more pronounced. It was not only that Husain left a world behind but a civilisational ethos that was multi-religious, multicultural and composite. It was ironic that Intizar Sahib invoked the Hindu, Buddhist and other mythologies in a country that he like thousands of others had seen as the new haven for a migratory populace.

In the initial years, Intizar Sahib was part of the intellectuals club that viewed art as being separate from politics. On the other hand, the Anjuman e Tarakki-pasand Musannifeen (Progressive Writers Movement) viewed literature as a vehicle for social change and engaged with the politics of the time. Intizar Husain and his mentor-friend Mohammad Hasan Askari , a towering literary critic and commentator, challenged the progressives worldview and held that the craft of fiction must not be subordinated to the political concerns of the day. This division continued for decades and became even more intense as the state cracked down on the Communist Party, setting a new ideological framework for Pakistani identity using Islam and everything that was not Indian in nature.

But Intizar Sahib was no rabble-rouser nor an ideologue. He straddled this world and by the time he wrote Basti in late 1970s, he had seen the dismemberment of Pakistan in 1971 and the decline of Pakistan’s imagined ethos (one has to still figure out what exactly that was given the contested imaginations of Pakistan that bedevil the national narratives). The novel refers to 1971 crisis but the characters refuse to take overt sides in the political conflict. The protagonist Zakir remains a participant in the larger flow of history but is trapped in the memory of a lost abode.

I remember reading an interview by Intizar Husain in which he had admitted that he had been writing one story all his life. To be precise, this was the story of lost identity, roots and the dilemma of finding new anchorage in a different soil. In an earlier story, Sheher i Afsos there is a line which sums up this anxiety: Have you seen that those people who get estranged from their own land are not accepted by any other land? (translation by Safdar Mir)

In 1983, a special number of the Journal of South Asian Literature was devoted to the works of Intizar Sahib. Herein, a key interview reveals the writer whose earlier engagement with Pakistani and Islamic identity is clearly under transformation: The Muslims came to India and formed ties with its soil. This attempt to understand the Islamic revelation in terms of our land, this endeavor to merge that revelation with our soil which yielded a unity that later was shaped into what we know as Indian Muslim culture. But we did not permit this unity to continue for long, as its progress has been constantly obstructed and halted.

This rupture of a unity and its later manifestations in Hindu-Muslim discord, the colonial experience and the Partition is what influenced the exploration of the hijrat mystique by Intizar Sahib through much of his large corpus of fiction.

Intizar Sahib’s contemporary Enver Sajjad, who was one of the pioneers of nai-kahani (or the postmodernist style in Urdu) questioned in one of his essays (published in a volume entitled Talash e Wajood): What would have happened had there been no Partition and if Intizar had never to migrate, what sort of fiction would he then have written? Would he have become a patwari of his soil due to the immense love for it? Indeed this was a tongue-in-cheek remark by a contemporary and a progressive author but it does raise an important question.

It is therefore appropriate to say that Partition and the experience of exploring a new identity made Intizar Sahib a unique creative voice. And his layered craft of using mythologies, colloquial references, folk expression and time traveling added to the richness of his storytelling.

Basti was published in 1978 and Intizar Sahib’s other major novel Agay Samandar Hay (The Sea Lies Ahead) was written in 1990s. I received the news of his illness and death while reading Rakhshanda Jalil’s excellent translation of the novel. The novel continues the stylistic features of Intizar Sahib’s fiction but there is even greater disillusionment with the Pakistan project here. Once again, the 1947 hijrat is compared to Prophet Mohammad (pbuh)’s shift from Mecca to Medina in the seventh century. Even in the Middle Ages, legends of migration took place when Muslims were evicted from parts of Spain. The protagonist Jawad Hassan faces forces larger than his agency. He is continuously haunted by memories of his birthplace, his childhood love and all that he left behind.

The dilemma of Jawad has autobiographical shades as the Pakistan dream has turned sour. Living in the backdrop of Karachi’s anarchic violence, Jawad is bitter about the corruption, a distorted society and the increasing religious-supremacist discourses.

Jawad’s existentialist crisis is deepened as he sees the new elites of Karachi, amid intense violence and curfews, indulging in kabab-paratha parties, and mushairas. Intizar Sahib also weaves a jihadist character in the form of Ghazi Sahib in the novel a figure whose later real-life manifestations have greatly harmed Pakistan in recent decades.

This was the transition of Intizar Sahib who had distanced himself from literature of a political variety. His column translated by Basharat Peer for the Granta magazine’s 2010 issue remains a fine critique of Zia’s Pakistan that we know all too well: What an era General Zia had brought to Pakistan! The echoes of prayer and the roar of public hangings.

Perhaps the most incisive line in this historic writing is: Along with religion, an unthinking nationalism had become the other god of Pakistan. Describing the culture initiated by Zia, Intizar Sahib writes:

General Zia aggressively nourished the Islamism that Bhutto had midwifed. Overnight, bureaucrats began showing up in mosques and rows of the faithful became a feature of the offices. At my newspaper, Mashriq (the East), there were a few devout men. The moment the call for afternoon prayer sounded, their pens would stop and they would leave for the nearby mosque. And now, the moment the editor appointed by the General stepped out of his cubicle, every reporter and editor would rise from his seat and head for the mosque. The madman stood with a razor on our necks. Rumour had it that two lists were being made: those who prayed regularly would be considered for promotion; those who didn’t . . .

There cannot be a wittier, sadder testament to this era. In his thousands of columns and essays, as he wrote consistently, the tone was never abrasive or self-promotional. This defies the Urdu column format which is largely ideological or political propaganda laced with self-praise and VIP attention-seeking. In Intizar Sahib’s columns was a pronounced focus on the environment particularly the trees, birds and references to nature. In fact when India carried out the nuclear tests in 1998, a key concern for Intizar Sahib was the fate of peacocks in Rajasthan. Such was the heart that remained pure, and a vision unalloyed despite all the disillusionments he faced and lived with.

I have been away from Lahore for more than twenty months. It is difficult to imagine a place without Intizar Sahib. I waited for Intizar Husain to return from the hospital. There was much that I wanted to tell him especially about my own hijrat experience and the way it has impacted me. Leaving Pakistan, even for some time, was not an easy decision. And not having visited the watan (homeland) for so long is even more traumatic. All of Intizar Sahib’s literary preoccupations make so much more sense to me. But I have also learnt from him that the sum total of human experience entails movements, explorations and the ultimate search to make sense of a chaotic world.

It would be a cliche to say that an era has ended with the passing away of such a colossal figure. For me, an old jamun tree was suddenly removed from the landscape of my life. I think Intizar Sahib would approve of my sentiment as the ancient Buddhist and Hindu cosmologies place a gigantic jamun tree at the centre of the universe. Of the seven continents of cosmos, the central happens to be Jambudvipa (the isle of Jamun).

Losing that is tantamount to a sorrow untold.

Raza Rumi is consulting editor at the Friday Times. He is also a scholar in residence at Ithaca College, USA where he teaches journalism and South Asia studies

– See more at: http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/remembering-intizar-husain/#sthash.0G3AbxhP.dpuf