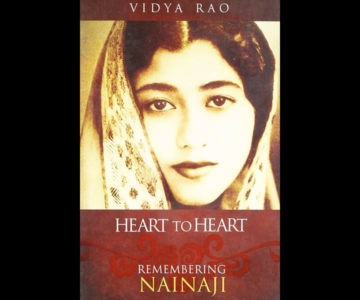

An essay contributed by the celebrated singer, writer and spiritualist Vidya Rao

I often ask myself the question why I choose, above all things, to sing, and then to sing a traditional gayaki like thumri. The images that are gleaned from its poetic texts are so often open to misunderstand: pining nayikas, heartless piyas, rakish Krishnas, divine Rams. I ask myself that question again today when tradition is in danger of being smothered by sectarianism, communal violence and a whole culture lies bleeding.

I turn to the music itself for my answer. It has never failed me before it does not fail me now.

I share with you then a few verses from lyrics that are part of this rich culture.

I share with you then a few verses from lyrics that are part of this rich culture.

There is a poem by Amir Khusrau, an especial favourite of mine. Khusrau says:

Ze haal-e-miskeen makun tagaful, dorae naina banae batiyaan

Ze kalb-e-hijran, nadaram ai jaan, na lehu kahe lagaye chhatiyaan.

As is customary, the lyrics express the anguish of unrequited love. As is customary too, these romantic lyrics are read as a metaphor for a divine love, this birha is our birha from the One.

But I move from both the explicit meaning of these lyrics and their easily read metaphorical meanings to the many implicit meanings, the dhvanis, hidden between the lines.

It is no accident, nor is it a gimmick that Khusrau chooses to compose this poem so that half of each line is in Farsi, half in Brajbhasha. Certainly, like several writers of the time, Khusrau was experimenting with the textures of the languages available to him, forging a new bhasha, new sounds. But what is also interesting is that language and the choice of language is not just an empty container that holds lexical meaning. Language itself is full of meaning. For us, reading or singing this poem today, other meanings, meanings embedded within the sound of language itself become available. And becoming available, tell us something about ourselves and our lives, our heritage, and our futures.

Because of the given conventions of poetry in Farsi and Brajbhasha, this simple text becomes incredibly rich and complex. Khusrau, speaking Farsi, is an anguished man addressing an indifferent beloved mashooq; speaking Brajbhasha, he becomes the nayika, a lovelorn woman yearning for her absent piya. Suddenly, Khusrau, born male, transcends the frontiers of his body, he is in turn, man, woman, aspires to an androgyny perhaps? Gendered identities collapse. I am forced to question this most basic sense of identity that I carry. I am now simply human. Neither man nor woman, and simultaneously both.

The world of men comes closer, merges with the cloistered world of women. In doing so, Khusrau collides spaces— the Farsi space of court, of politics, of written literary traditions, and the Brajbhasha space of field and home, of intimacy and nurture and everyday speech. I am coaxed out of my known spaces, into the vastness of Space, into the moment of simply Being.

The filigree of Farsi sounds flows into the earthy terracotta of Brajbhasha, delighting my ears. My tongue tastes these very different flavours and textures of sound. This is, I realize an extraordinary rasa!

The love that Khusrau speaks of is known to be his own devotion to his Pir. It is a divine love of which he speaks. But the words that he uses to speak of it are not so poor as to reject the truth of ordinary human loving– the love of women and men for each other romantic love, conjugal love. And, I hear it also as a love of one’s fellow beings – human and non-human.

This love of which he speaks– I see it in my own life as a love of and commitment to music, that most elusive Beloved. But for me it is also a love of the richness of the cultural traditions of this space I call my homeland-a culture which was then, as now, in the process of being made, and which, by his articulation, Khusrau has helped to make, just as you or I, living our ordinary daily lives, doing our ordinary everyday work, help to make. It is a making that has, moreover, to be done with love, with care and with humility.

This Khusrau, this fine soul who speaks to me across the centuries, my heart contracts with pain and fear to think that one day, some blind, misguided soul might declare him to be a foreigner, an invader. If Khusrau, beloved Khusrau, were to be banished, I know I would waste away like the birahini nayikas of one of my songs. I would be depleted.

At another time, in another part of India, a woman called Meera had sung:

Nahi aiso janam barambar

Ka janoon kachhu punya pragati,

Manusha avatar.

I think that what she tells me is this: There is an extraordinary good fortune that is mine, to be born here a woman, singer, Indian, to be heir to this shimmering tapestry that is my history and my culture. Where else but here, how else but being born who I am, could I claim as my birthright the songs of the Qawwals of the dargah of Hazrat Muinuddin Chishti and Hazrat Nizammudin Aulia, the chanting of hymns at Kashi Vishvanath, the silence of Sarnath. The heat of the rocks on Arunachala Hill, the icy cold of Himalayan snow. The blue of the western sea, the sentinel boulders of the Deccan. Were else could I claim the right to speak in a hundred languages, all mine, all deeply loved? Where else worship in a thousand different ways, where thrill to the touch of the charming Kanha, where lose myself in the complex metaphysics of Nalanda, where weep and mourn the martyrs of Karbala? Where else could I rejoice to see the flames of blooming tesu and semal, and the lace of kachnar blossoms, where fill my lungs with the scent of reborn rain-washed earth?

Poets, artist, singers, dancers, mystics, ordinary men and women have, over the centuries, filled in the stitches of this beautiful fabric of my culture. Like Kabir I take it in my hands and sing:

So chaadar sur nar muni odhe, odh ke maili keeni chadaria

Das Kabir jatan se odhe , jyun ki tyun dhar deeni chadaria.

First published in the journal, Equality.