Book Review by Sumaira Samad

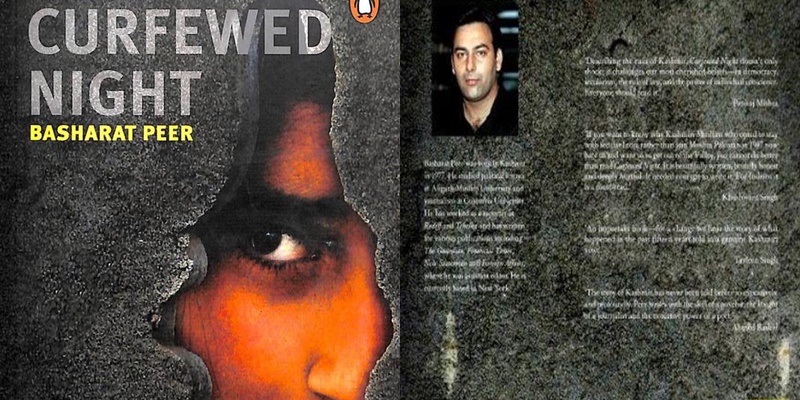

Curfewed Night is the memoir of young Kashmiri journalist Basharat Peer, recounting his youth in the troubled valley during the ’80s and ’90s. A harrowing look at the political strife and armed conflict that has torn Kashmir apart over the last 30 years, Curfewed Night is nothing if not personal. The people, places and events Peer describes are ones he encountered and experienced first hand. They are his parents and neighbours and friends. Yet, despite this intimacy, essential to any good memoir, Peer’s narrative is refreshingly honest, frank and unbiased. His is no polemic, and sentimentality, self-pity and melodrama take a back seat.

Beginning in the years before the struggle, Curfewed Night invites the reader into a beautiful, peaceful mountain paradise where the regular, slow rhythms of village life make up one’s existence. Peer lives a happy, uneventful childhood, surrounded by a loving family and tight knit community. But this apparent serenity, as it turns out, is merely the glassy surface, hiding a quagmire beneath. The shadow of Kashmir’s turbulent history and unresolved conflicts never quite goes away, and even in Peer’s happy childhood, he knows that his home is one struggling for an identity. Kashmir, he tells us, is defined negatively, in terms of what its residents do not want it to be. That is, Kashmiris are certain that they do not want their home to be swallowed up by a larger India that has failed to give them the autonomy, rights and the self-respect that they expected at the time of independence. Kashmir has become the purgatory of the ghosts of Partition.

Curfewed Night takes readers on a journey exploring the hopes, aspirations and frustrations of the Muslims of Kashmir, focusing especially on the youth and the path of armed struggle that these youth took to throw the yoke of Indian hegemony. Peer shows us through the deeply touching stories of others, through mothers, sons, poets and militants, the complexities that are inevitably involved, refraining from presenting a Manichean picture of Muslims versus Hindus, or Islamic fundamentalists versus secularists. No, he insists, the Kashmiri Muslims were never orthodox, and they lived under the influence of such Sufi saints as Nuruddin Rishi, the valley’s patron. The initial movement for independence, led by JKLF, began as a struggle for an independent, secular Kashmir, neither part of India nor Pakistan. It was also partly a class struggle; the majority of its members came from the lower middle and peasant classes. It was the struggle of a people who had over the years felt alienated from mainstream India, neglected and taken for granted. The problem, Peer argues, really began after the Indian government brutally sought to crush the independence movement, when it was taken over by fundamentalists.

Curfewed Night is neither purely political analysis nor journalistic vignettes. It tells the stories of ordinary people caught in politics. But, importantly, these stories are not journalistic “facts” they are lived experiences.

Indeed, Peer tells the story of all Kashmiris, whether Muslim or Hindu. He tells us about the misery and grief caused to human beings, regardless of their religion and class. He bluntly presents the brutalities of the Indian army and paramilitary, but also does not fail to show the brutality of the militants. The complacency of the bureaucracy, whether of the Indian state or the Kashmir state; the discrepancy between the leadership of the militants and political leaders; and the rending of ordinary lives due to military and militants alike are all touched upon in Curfewed Night. And the change in the mental landscape of a people now ruled by uncertainty and fear is reflected in the besieged landscape of this valley, once legendary for its beauty. As Peer writes, “The poet lied about its being paradise.”

This is the story of an agonised people whose lives have been torn asunder by factors beyond their control. These are a people who have been fighting for their legitimate rights and have been crushed by an iron hand, indiscriminating and unrelenting. For Pakistanis, battling strife within their borders due to various armed struggles, terrorist attacks and state aggression, the story told by Peer surely will provide insight into our own troubles. It takes us beyond media reportage to the people – to their homes, schools, colleges and universities, inside their daily lives, their festivals and funerals – to an existence that is not very different from yours or mine. Curfewed Night reveals the connections between what is happening in Kashmir and what is happening in Waziristan and Swat, and what is happening beyond Pakistan in Afghanistan. The terrain changes but the story can be stretched into countless homes.

Peer ends the book with a note of hope, closing with the introduction of a new bridge across the Line of Control. Kashmiris, from both sides of the divide, cross this physical and metaphorical bridge, greeting each other with rousing welcomes.

First published in The Friday Times