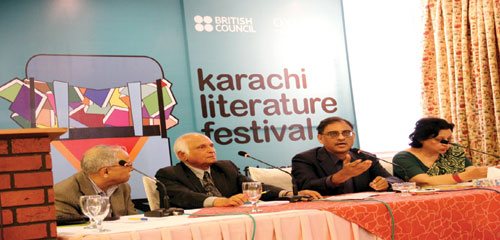

Huma Imitiaz has summed up the session I moderated at the KLF. Huma has been kind to me but I am just a humble student of literature and facing Intizar Saheb in this session would remain a milestone in my imagined literary journeys, yet to start…

There are two forces that have risen in Pakistan: women and mullahs, said writer and journalist extraordinaire Intizar Husain, at the Karachi Literature Festival. The crowd roared in approval, and Husain smiled. At his session, held on the second day, the room was nowhere near full capacity, but those in attendance were hanging on to his every word. In a one on one discussion with writer Raza Rumi, Husain talked about a variety of subjects, from writing techniques to the Lahore that once was.

Instantly putting his interviewee at ease, Rumi skilfully steered the conversation: on technique, Husain talked about his influences and how he came across various narrative styles in historical texts, including Buddhist writings and the Mahabharata. The conversation flowed to Husain’s journalistic career and his first job interview: as a fresh graduate in Urdu, Faiz Ahmed Faiz had interviewed Hussain for the post. Faiz sahib asked me, “You’ve done your masters degree in Urdu?” I replied, “Yes”. There was a long silence. Then he asked, “You’re from Meerut.” I said, “Yes.” There was another long silence. Then Faiz sahib said, “Well, there’s a delay with the paper, but you will receive word.” I thought, Faiz sahib is just making excuses, but lo and behold, word did come, and I was hired. This was Husain’s first job as a journalist at Pakistan Times after which he joined the Urdu daily Imroze.

Husain recalled his experiences at Imroze and how the editors envisioned changing the face of Urdu dailies and setting new standards. He touched upon the demise of the cafe culture in Lahore, mentioned in his book on Lahore, Chiragon Ka Dhuwan, and painted for the audience a picture of Mall Road in its heyday, when it was full of a plethora of restaurants and cafes patronised by writers, intellectuals and poets. The demise began when Ayub Khan allowed rikshaws to come on that road, remarked Husain.

Civilisations can be traced to their mode of transportation, said Husain, citing how the second major moment was when the motorcar arrived, ending the pedestrian culture in the city.

Husain’s tete-a-tete with Raza Rumi also highlighted the importance of having a good moderator at an event, one who is familiar with the interviewee’s work and life. Rumi was well-prepared, and asked articulate questions that brought various aspects of Hussain’s life and work to light.

Another session that stood out at the Karachi Literature Festival was Mohammed Hanif’s conversation with five Pakistanis well-versed in regional languages: translator Bilal Tanweer, who translated three of Ibne Safi’s stories from the Imran series, Hassan Dars, a Sindhi poet; Ali Akbar Natiq, a Punjabi poet and writer; Mudassir Bashir, a Punjabi poet and writer and Attiya Dawood, a Sindhi and Urdu poet and writer.

The panellists read out evocative poetry and writing from their repertoire of work, followed by wah wahs from the audience. Natiq, who hails from Okara, the same district of Punjab that Hanif belongs to, recited a beautiful poem describing his village. Following the recital, Hanif wryly remarked, “I don’t know what village he lived in, but that’s not how my area looked like.”

The panellists talked about the importance of writing in their own language, and what came naturally to them. Hanif, while talking about learning regional languages and the state language, said that when one learns, for instance, Punjabi as a child, by the time he is five years old and goes to school, the language becomes redundant, as he has to now learn everything afresh in Urdu.

As the session came to a close, one left with the hope that the limelight would soon fall on the poets and writers writing in regional languages.