Pakistan’s permacrisis has only deepened through 2022. Raza Rumi on what 2023 holds for the nuclear armed crisis state.

As the year 2022 ends, Pakistan’s deepening crisis of governance appears to be intractable. For all practical purposes Pakistan has defaulted without a formal announcement. The foreign exchange reserves have fallen to a historic low of $6 billion, with no sign of an immediate tranche release from the International Monetary Fund. The situation might get even worse. With complete elite capture of the economy, shoddy management over the years and static exports, things are not going to change in the short to medium term. This is a perennial crisis fueled by manufactured political instability largely due to the desperate attempt by the military establishment to retain control over national affairs.

While a murky era that ran from 2016 to 2022 seems to be ending, the unbridled ambitions of senior military bureaucrats were laid bare during the year. As if these crises were not enough, the year 2022 also witnessed a return of terrorism – a direct offshoot of a failed Afghanistan policy that requires urgent recalibration. The colossal cost of political engineering is such that 2023 will be spent rectifying flawed ‘interventions.’

The colossal cost of political engineering is such that 2023 will be spent rectifying flawed ‘interventions.’

2022 started off with the widely recognized split between former prime minister Imran Khan and the military junta (save a few generals who had different plans for Mr. Khan). The opposition, sensing this fallout, jumped at the opportunity of dislodging Khan and his party Pakistan Tehreek-E-Insaaf (PTI) from power. The intense political bickering and machinations led to Khan’s final ouster on April 10. However, in the process the Constitution was trampled, parliamentary norms were thrown to the wind and Khan, in a Trumpian manner, resisted his exit from PM house till the very last.

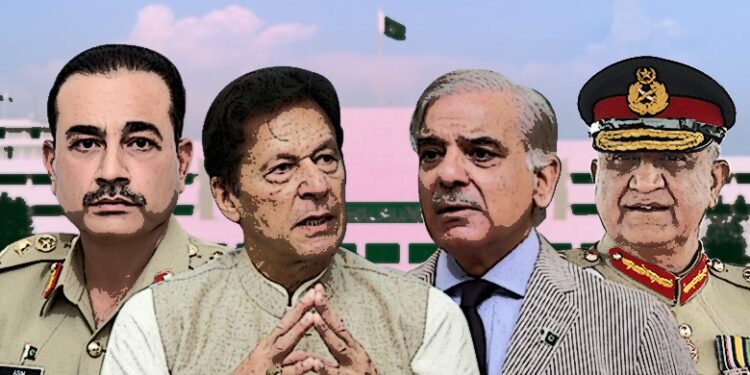

Pundits had assumed that due to his disastrous record in office for nearly four years, this regime change would be a smooth, typical affair. They were in for a great surprise as Imran Khan, aided by sections of the deep state, private media, a handful of business tycoons and a large urban middle class pushed back against the new government – a coalition of 16 parties – led by Shehbaz Sharif. More significantly, this new constellation of social forces challenged the former military chief General Bajwa and his associates like never before. For months, the army chief was labeled by PTI social media troll farms as a ‘traitor’ and a disingenuous foreign conspiracy narrative was repeated ad nauseum that it acquired a reality of its own. This massive propaganda onslaught entailed relentless political messaging by Imran Khan through more than a hundred speeches and more than 60 rallies across the country. In the absence of Nawaz Sharif or such like popular figure, Imran Khan was, and is, the only game in town.

For months, the army chief was labeled by PTI social media troll farms as a ‘traitor’ and a disingenuous foreign conspiracy narrative was repeated ad nauseum that it acquired a reality of its own. This massive propaganda onslaught entailed relentless political messaging by Imran Khan through more than a hundred speeches and more than 60 rallies across the country.

The high pitched, agitational persona of Imran Khan received covert support from senior figures within the military establishment as well as within the judiciary, and much of the media industry. Observers were quick to note that in the 34 years post-Zia, ‘ousted’ prime ministers were never given a free pass as Khan received. By the middle of the year, it was clear that this political battle was neither about an early election nor was it a cry for ‘real independence’ from the West. It was a populist expression for intra establishment contest over the appointment of a new army chief due by the end of November 2022. By September, Khan spilled the beans and demanded that the appointment of Army Chief was his prerogative. There is no law that allows the opposition leader to have a say in this decision-making process, but Khan and his charged middle-class supporters thought otherwise.

The fledgling PDM government did not budge. It patiently waited for November to arrive when they could play their trump card through the appointment of new army chief. On November 27, PM Shehbaz successfully managed to appoint a chief who was not a candidate of Imran Khan and his benefactors within the system. A fresh beginning was heralded with the installation of a relatively apolitical army chief calling the shots, who, in recent days is reportedly taking steps to put his own house in order.

Given Pakistan’s chaotic history, no one is willing to believe that the army has withdrawn from political affairs but the institution surely has learnt its lesson: betting on an erratic horse is not the wisest of strategies. The tactical retreat from the political arena is likely to continue during 2023. However, this phase is going to be short-lived given the intense polarization and the inability of the civilian sphere as a coherent power centre governed by some basic rules of the game.

Speculation is rife about the appointment of the long-term caretaker government comprised of the technocrats to steer the country out of the economic crisis. This is not likely to work.

The greatest hit through this fiasco was taken by the military establishment, as it lost some of its prestige and insular status in the society. Imran Khan was successful in creating a wedge between historic bedfellows – the middle class and the establishment by playing up divisions, both real and imagined. Rumors of factionalism gained currency with intense social media [dis]information and the resignation of two generals after the appointment of new chief gave traction to such speculation. The brutal murder of TV anchor Arshad Sharif in Kenya, the attack on Imran Khan and cases against PTI leaning journalists and activists wrought further anti-establishment sentiment. This is a challenge that the new army chief will have to contend with.

Speculation is rife about the appointment of the long-term caretaker government comprised of the technocrats to steer the country out of the economic crisis. This is not likely to work. Technocrats will lack legitimacy and could potentially face the combined wrath of all political forces. Such an experiment will also tilt the scales completely in the favor of military which would ultimately become untenable for both Nawaz Sharif and Imran Khan.

During 2022, the country finally woke up to the specter of the climate crisis with the worst natural disaster to hit the country in over two decades, displacing more than 33 million people and causing over $30 billion in damage. Perhaps the best news of the year was Pakistan’s valiant and effective advocacy, led by Minister Sherry Rehman, for the setting up a global ‘Loss and Damage fund’ – a concrete step towards the attainment of the climate justice. The monsoon season of 2022 revealed the sheer lack of disaster preparedness and lack of priority given to climate adaptation. The callousness of Pakistan’s ruling classes towards its poor came through as a rude reminder that a country with a substantive nuclear arsenal was straddling broken systems of planning, no local governments or safety nets for the poor. It is a surprise that the brewing public anger has not turned yet into a mass uprising. The political elites couldn’t care less about the disaster. As the country drowned, Imran Khan kept on rallying across the country for an army chief of his choice.

Pakistan in 2023 is going to need visionary leadership, a functional parliament, structural policy reforms and sacrifice by its elites to tackle the interrelated political, economic and security imbroglio.

The prospects for 2023 are even bleaker. With the Pakistani Taliban and their affiliates, and the Baloch separatists mounting attacks, the state is left embroiled in a quagmire. State power, legitimacy and resources are going to be under immense duress in the coming year. Pakistan in 2023 is going to need visionary leadership, a functional parliament, structural policy reforms and some degree of sacrifice by its elites to tackle the interrelated political, economic and security imbroglio.

Sadly, none of these requirements for stability are on the horizon. This is the ultimate dilemma and tragedy that Pakistanis will have to contend with in 2023.