Pakistani paramilitary soldiers march during the 18th passing out parade for the Rangers basic recruits training course at the Sindh Rangers Training Centre in Karachi, November 11, 2014. Some 1,122 rangers were inducted following completion of their training. AFP PHOTO/Rizwan TABASSUM (Photo credit should read RIZWAN TABASSUM/AFP/Getty Images)

Pakistan military retakes pivotal control, and the public does not seem to mind.

Pakistan military is back in the driving seat. This time, not through a conventional coup detat, but through an amended constitution that enables military tribunals to try civilians accused of terrorism.

On Jan. 6, in a joint session, the Parliament amended the country constitution to establish military courts. The Islamist parties, opposed to the inclusion of the term religious terrorism, backed out at the last minute. But the major secular political parties, ostensibly committed to democratic rule, passed on the judicial powers to special military courts for a period of two years. This is a significant blow to the democratic transition that occurred after Gen. Musharraf ouster in 2008, when the country returned to civilian rule.

The unenviable history of democratic evolution in Pakistan is well known. The military directly governed for more than three decades, and in the periods of so-called civilian rule (such as the present one), the military retains control over security and foreign policy. Pakistan military is also synonymous with the nationalist identity and therefore shapes the political discourse as well.

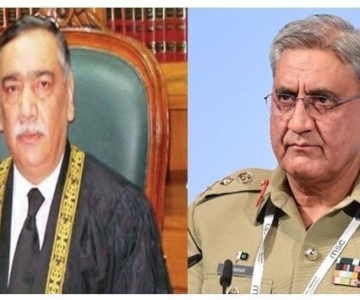

The current prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, assumed office in June 2013. In November, he appointed a new Army Chief, Gen. Raheel Sharif, thinking that he was consolidating civilian power. Sharif also pushed for the trial of former President Musharraf (who ousted Sharif in 1999) for violating the constitution by imposing emergency rule in November 2007.

In April 2014, Gen. Musharraf was indicted for high treason under the constitution, but the trial did not progress very far and now seems to be stagnant. This was where the tension between Sharif and the military first manifested.

Last year, Pakistan powerful Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) effectively tamed the country noisy broadcast media. In May, Hamid Mir, a leading host at the country largest private TV channel, GEO, was attacked by unknown gunmen, leaving him seriously wounded. Mir family accused the ISI of being involved in the attack and his employer, GEO network, gave excessive coverage to the allegation.

Not surprisingly, the military was furious. Soon, almost all media barons came out in full support of the ISI, and maligned GEO, which was suspended from broadcasting as a punishment for bringing national security institutions into disrepute.

This was an ideal environment for the televised agitation against Sharif government. From August to November, the government in Islamabad was virtually brought to its knees by street protests led by opposition leader Imran Khan. The former head of Khan party even confirmed the involvement of retired military personnel in orchestrating the protests. Khan and sections of the media openly called for the intervention of the ostensibly neutral umpire a euphemism for the Army Chief.

The Army did not launch a coup, as it would have been counterproductive given its battle against insurgents in Pakistan northwestern tribal areas and the southwestern province of Balochistan. However, a weakened civilian government ensured that changes in foreign policy could be easily averted.

For instance, Sharif wants to open up trade with Pakistan arch-rival, India, and also pursue a policy of noninterference in neighboring Afghanistan. Both of these policy objectives conflict with the strategic worldview of the military that considers India as a perennial threat and an instigator of the insurgency in Balochistan.

Not that India has helped matters. To appease his domestic hardline Hindu-nationalist constituency, its new leader, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has ramped up his rhetoric against Pakistan.

The deadly attack on the Army-run school in Peshawar on Dec. 16 led to an unprecedented national unity against terrorism. The Army seized the moment to intensify the battle against Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Sharif announced a national action plan against terrorism, endorsed by all political parties. Most of these civilian initiatives were clearly pushed by the military.

The underlying failure of democracy has to do with an outdated and contested electoral system, political parties run as family empires, and little or no move toward any type of reform. This creates a situation where the Army is seen as the neutral and credible institution that can rescue the country. In effect the Army de facto political role is embedded in the national politics and governance.

Sharif tried to gain control of Pakistan foreign policy and wanted to hold the former dictator accountable, but was soon faced with the reality. To survive in office, he would have to share power with the khakis.

Pakistanis outraged at the Peshawar incident are content with the civilian surrender in the form of the constitutional amendment. The Army chief has expressly stated that military courts are not the desire of the army, but need of extraordinary times. Many in Pakistan believe that civilians had no choice but to go along with the new military-dictated policy.

Over the last two weeks, the Army chief has been chairing meetings of provincial apex committees, comprised of civilian provincial officials and military representatives. While such coordination can overcome the intelligence gaps and failures, the symbolism of the Army chief leading such meetings is not lost.

Military courts and provincial committees led by military commanders denote a more sophisticated, postmodern coup by which the Army oversees civilian governance, without an outright takeover. This arrangement is reminiscent of the Turkish National Security Council (NSC), a constitutional body, where the military has become legally a part of the civilian decision-making process. Despite Erdogan efforts to reverse the military active role in Turkey political sphere, it still guides and advises the politics of the NSC.

Large segments of Pakistani public opinion shaped by the conservative, urban middle classes backs the military, since it views elected leaders as incapable of delivering either stability or change. The media, which recognizes where the power lies in Pakistan, reinforces such a worldview. This is a worrying sign for the future of democracy in the country.

The new emphasis on hanging terrorists and viewing terrorism as judicial failure are myopic solutions to a more complex problem that emanates from the security policy Pakistan has had in operation for decades, which has historically considered private militias as arms of state policy. The constitution bars the existence of private militias, yet they exist in the dozens making a mockery of constitutionalism.

The usual advice of the West telling Pakistan to do this or that is likely to be counter-productive. The leverage of the international community, including the United States, is limited. Only Pakistan civilian leaders can engage with the military to reshape the country foreign and security policy and undo the jihad infrastructure that was put into place since the 1980s. For now, this undertaking seems difficult.

Citizen groups have been protesting across the country often using social media for a crackdown on symbols of jihadism. They will have to extend their advocacy and pressure the political parties to implement more reforms, introduce local governments, and shun opportunism. Pakistan Parliament and provincial administrations will have to initiate urgent reforms to fix the collapsed criminal justice system that makes military courts look promising to an average Pakistani, which will take time.

This is why Pakistani public which ousted Musharraf through a popular movement in 2008 is looking once more to the generals. This may appear to be a paradox, but it summarizes the story of Pakistan.

Original Article here