In celebrating his pluralistic literary roots, Intizar Husain was a truly contemporary writer.

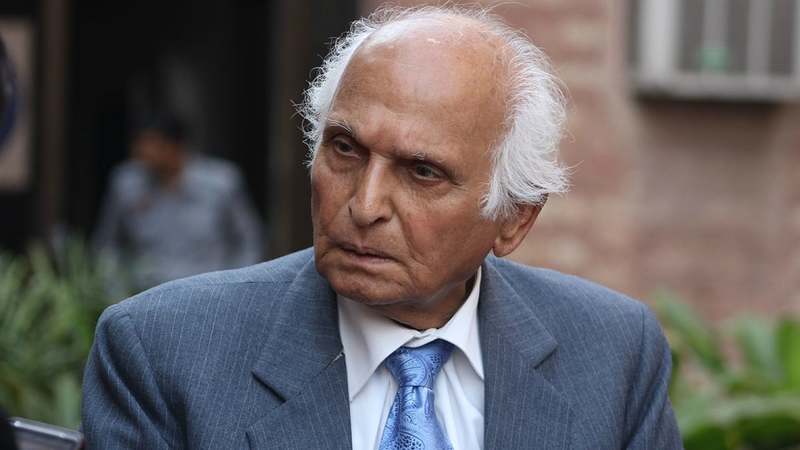

Intizar Husain, the last of great Urdu writers, passed away yesterday at the age of 92.

He’d been hospitalized for some time in Lahore. His ardent followers had been worried that the worst was likely to happen. But the truth is that writers of Husain’s stature never die. They live in their words and the corpus of ideas that they bequeath to future generations.

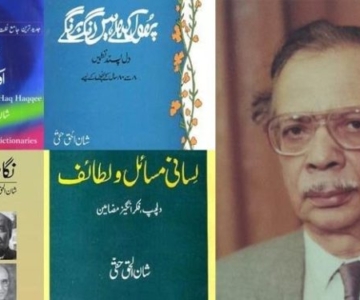

Husain was definitely one such figure. He leaves behind some of the finest specimens of fiction, journalism, travel writing and critical essays. The sheer volume of Husain’s literary output is mind boggling as it indicates a life that was lived in a deep love of letters; engaged in an eternal search for meaning.

Intizar Sahib spent his early years at his birthplace Dibai in the Bulandshahr district of Uttar Pradesh (UP), India. In one of his interviews, he said that the partition of India in 1947 made him a fiction writer. Nothing could be truer as the shadow of his migration to a new country became perennial. For much of his life, this event and the sense of displacement informed his creative musings.

Husain did not renounce the enemy and continued to celebrate his pluralistic literary ancestors. This fact alone places him in a distinctive category of a contemporary Pakistani writer.

As the new country searched for an identity, the early years of Pakistan witnessed intense ideological struggles within the intelligentsia.

Lahore-based writers were factionalized in two camps: the left-leaning progressive writers and the more nationalistic ones who comprised the Halqa-e-Arbab-e-Zauq. Husain did not choose a side and was castigated by the progressives for not taking an overt position and more importantly, for Husain’s affinity with Mohammad Hasan Askari who was at the center of defining Pakistani literature no less informed by religious sensibilities.

The irony is that in contemporary Pakistan, Husain became the voice of toleration and inclusiveness.

His columns expressed clear positions on several issues including the rise of bigotry and extremism in Pakistan. That said, Husain was not a polemicist and therefore his writings retained their literary mellowness and an aversion to making art subservient to politics. Husain was also familiar with Western traditions and through translations had internalized many a tenet of literary craft. However, it was the composite culture of the Indian subcontinent, ruptured by 1947, that remained the greatest of inspirations.

In fiction, Husain’s style was deeply influenced by the myriad streams of mythologies and fables from the Indian subcontinent and outside. In dozens of short stories that he wrote, symbols from past lives were invoked. His writings referred to Alif-Laila, dastaans and ancient tales such as Panchtantra, Jataka Katha, Mahabharata and the Vedas. This literary divide irked some of the more hyper-nationalistic writers and critics, as Husain did not renounce the enemy and continued to celebrate his pluralistic literary ancestors.

This fact alone places him in a distinctive category of a contemporary Pakistani writer.

But it was his migrant’s experience, and a sense of exile within home that was a recurrent theme in fiction. Even though he was deeply invested in Pakistan, the memory of his birthplace and the trauma of hijrat also linked to the Islamic traditions was discernible. Husain had a huge following in both Pakistan and India; and not unlike Qurratulain Hyder, his work bypassed hardline allegiances.

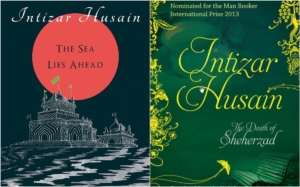

Among the five novels he wrote – Chaand Gahan (1952), Din Aur Daastaan (1959), Basti (1980), Tazkira (1987), Aage Samandar Hai (1995) – Basti received global acclaim. Its English translation was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2013. Husain was conferred the ‘Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters’ by France in 2014. Pakistani state recognized his stature and conferred several accolades including the Sitara-e-Imtiaz and Kamal-e-Fun award.

Even though Husain was deeply invested in Pakistan, the memory of his birthplace and the trauma of hijrat also linked to the Islamic traditions was discernible.

Basti, a vaguely autobiographical novel, recounts the adjustment of its alienated central character after Partition. The (anti) hero Zakir’s experience is not too different from many others across the globe who are displaced or live in a state of uprootedness. Aage Samandar Hai, recently translated into English by Rakshanda Jalil, is set in Karachi. The novel not unlike Basti takes the issue of a Muhajir identity in the context of present-day urban violence of Karachi. While set in the region, both these novels explore the larger tragedies of human travails.

My personal favourite is Husain’s memoir Chiraghon Ka Dhuvan that was published in 1999. This book recreates Lahore of early years, its teahouses, vibrancy, decay while documenting many characters that we would have otherwise forgotten. Husain’s autobiography Justujoo Kya Hai published in 2012 is also written in his unique UP-dialect and the author remains a self-effacing, penetrating observer of life.

It would take many years, if not decades, to adequately assess the legacy of Husain’s literary feats. But this is the time to remember a life where imagination reigned supreme. A vision so splendid that it unremittingly relived the vanished millennia, while attempting to make sense of the present.

Farewell Intizar Sahib. Your journey continues.

Featured photo by Hamza Cheema