I met the wife of slain Minister Shahbaz Bhatti and discovered tales of woe, marginalisation and hope

It has been over three years that Pakistan lost a brave Christian citizen Shahbaz Bhatti for his relentless advocacy of human rights and in particular for wanting to correct discriminatory and anti-people laws that afflicts all Pakistanis Muslim or non-Muslim. Shahbaz Bhatti’s case has been treated in the same manner as most cases of this kind are. There are high-sounding condemnations; initial activity by the Police, arrest of a few suspects and then the dysfunctional, collapsed system of justice takes over.

Shahbaz Bhatti was a serving Minister at the time of his murder. This was the second loss for the PPP an ostensibly liberal and secular party in power. Earlier it was Punjab’s Governor Salmaan Taseer who was assassinated by his own guard in 2011, and in the same year a federal minister was gunned down in broad daylight. Yet, the response of the government was not what it ought to have been. By caving in to the extremists pressure and keeping survival in power as the top priority it lost the chance of changing the direction of the country. True, PPP was beholden by powerful corporate interests of the military and a formidable armed right wing but the impact of it all has been grievous for the country.

Taseer’s son is in the custody of militants since 2011. The former Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani’s son was also abducted by militants and remains a hostage. The public opinion in Pakistan is not concerned, as the middle class narrative holds the corrupt politicians responsible and militancy is now viewed as a heroic resistance to the evil West. This is why Shahbaz Bhatti’s killers are free and the case most likely will lead to another unjust outcome.

I am sometimes an object of scorn for not being ready to face more bullets for a radicalized society

Leaving Pakistan was not easy and I still suffer from the slings and arrows of loss. Howsoever temporary a sojourn is, forced exit from your work and life is traumatic. Luckily I am alive. But I am in a strange category now. A survivor. Banished. An object of sympathy, pity and sometimes scorn for not being ready to face more bullets for a radicalized society. Having said that I am now in touch with many characters of the grand tragic story of Pakistan. Among others, a most notable acquaintance I have made is the wife of slain Shahbaz Bhatti who lives in the United States as well.

We corresponded some time back and later met in person. Salma attended my book reading (of Delhi by Heart published last year) that was organized by a South Asian arts group called Saaz Inc. in Philadelphia. It was an eerie feeling and the connection we made was instant and heart-warming.

I am now in touch with many characters of the grand tragic story of Pakistan

With her large, sad eyes Salma told me bits about her time in the US and all that she had gone through in recent years. She was raised by her uncle who was also related to Shahbaz Bhatti. Her marriage with Shahbaz Bhatti whom she lovingly calls Cammy was solemnized against the conventions as the two families were not too keen for it to happen. But Salma was not just a wife. She became Cammy’s partner in his politics, activism and public life. Whatever he wrote and did, Salma was a part of it. She has tonnes of emails, text messages and documents with her that indicate how deeply she was involved in his political work to improve the status of Pakistani minorities.

When Shahbaz Bhatti was assassinated in 2011, this was the end of Salma’s life too. But her tragedy was manifold as the in-laws turned strangers and disowned her. Because Cammy’s family had not approved of their marriage this was the time to settle a perverse score and also not let her appear as the legatee of his work.

Wailing and devastated she was meted out the typical treatment that fallen daughters-in-law are given. Someone from the larger family administered tranquilizers so that she could remain out of the scene. For the Bhatti family, according to Salma, this was a matter of honour. Shahbaz had not only taken on the world, he had also married against the will of the clan.

Her physical state prevented her from attending the funeral. When I heard this story I felt as if a page from Marquez’s novel had fallen off and landed before me. On the other hand this is commonplace. While the Bhatti family found a way to move out of Pakistan and migrated to Canada along with the house maid, Salma was dumped in Pakistan to face threats.

Through sheer will power and her ability to gather the pieces of her life, Salma managed to migrate to the US and find a new life. But this was not easy. She faced depression, isolation, abandonment and of course the daunting task of becoming financially independent in a new country. That she is alive is also remarkable for I was told she tried to commit suicide at least three times.

We stood there on a crisp autumn day and faced each other. Two apparitions of ourselves. Two lost and meandering spirits. I would not have fathomed this connection had I not been through my recent travails. She told me all about her efforts to enroll in a degree program, looking forward and her attempts to move on. But each time she uttered the name Cammy a shadow would touch her face and a moment of sadness would descend.

I learnt about her efforts on advising Bhatti on legal reforms, picking up issues, reaching out to various international networks and organisations. In particular the work that Cammy undertook for the Christian community and other minorities was also mentioned. This was a full, robust life of standing up against the odds and dealing with all the constraints that Pakistan has erected in the realization of human rights.

There is a video https://vimeo.com/87746794 that a Philadelphia based educationist and activist Victor Gill has prepared to mark the third anniversary of Bhatti’s murder. Gill has been a major support for Salma and has literally taken her out of the folds of her death-wish. The video shows the memorial service held for Bhatti on April 15, 2011 with all of his relatives excluding the love of his life Salma. In that clip, Salma appears on the screen as an invisible woman and the sound of her footsteps is heard. Almost as a ghost she walks up to Cammy’s brother and a sister who are standing next to Bhatti’s large portrait, but remains aloof. Her key focus is on Cammy’s eyes and remembers all the moments of happiness and camaraderie she spent with him. The invisible woman then goes to the church service where the famous hymn Amazing grace is being sung. Salma, the ghost spots her mother-in-law in the front row, and Bhatti’s brothers Girard and Peter among others, and asks a question,Why is it so dark? For sure Salma has seen too much darkness.

The video finally moves to Salma’s interview with Hamid Mir in August, 2013. This is when she speaks out and ends her silence. I had been with Cammy for 15 years, she says but the marriage was kept a secret in deference to Cammy’s father who did not approve it due to cultural and conventional reasons. The video is in effect a public message for Salma’s in-laws and members of the political party All Pakistan Minority Alliance (APMA), reminding them that abandoning Salma is a travesty of Bhatti’s memory and legacy.

She said to me, Cammy was me and I was Cammy. If anyone claims to know Cammy more than me, he is a liar, hypocrite and an opportunist but that is what happens with how the survivors play politics of power and exclusion and Salma has been an obvious victim of that.

Salma has a plethora of documentation including two emails showing how her in-laws communicated to Cammy through her; and how she had begged Cammy to stay in the USA in 2011 as he faced multiple threats. But poor Cammy, the brave man, was determined to return and do his work. Within weeks of his return to Pakistan, Bhatti was assassinated.

Salma is vulnerable and precious. But such is the tragedy of our society and cultural mores that she has been forsaken by all and sundry. The PPP should acknowledge her and the unfinished tasks that the two were undertaking. Similarly, Christian associations and groups need to advise their community not to replicate mainstream-style marginalization within their folds. It serves no purpose.

I am happy that I found Salma and other fellow-exiles who give me the strength to move on and rebuild a derailed life.

The third hand

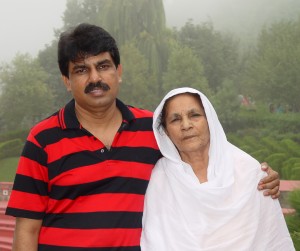

Salma with Shahbaz Bhatit’s sister, Jacqueline Bhatti. She was once the center of attention for the Bhatti family

There is something not quite right in the minister’s assassination, writes Victor V Gill

The speedy bails of slain Shahbaz Bhatti’s confessed killers had raised many eyebrows regarding the possible involvement of a third hand in connection with this high-profile murder case. Bhatti’s brutal assassination in broad daylight in front of his residence on March 2, 2011 received worldwide attention, as he was the only federal minister belonging to the Christian minority in Pakistan. After much public and international pressure, the Pakistani government in a face-saving attempt, arrested Umer Abdullah and his two accomplices in September 2013, but only to grant them bails in July 2014, less than a year later.

On the day of Bhatti’s murder, several flyers bearing the name of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh), were dropped at the site of the murder; supposedly by the Taliban. According to those flyers, Bhatti was alleged to have blasphemed when he ventured to initiate amendments in Pakistan’s controversial blasphemy laws. But Taliban are religiously devoted people and it would be beyond anyone’s imagination that they would throw a flyer on the ground bearing the name of Muhammad (pbuh) who they greatly revere, says human rights activist Joseph Francis of the Centre for Legal Assistance and Settlement. Advocate Raja Nathaniel Gill, who had also been a member of the Government’s Joint Investigation Team agrees with such a notion.

Two months prior to Bhatti’s murder, another high profile murder took place in Islamabad when Salmaan Taseer, the Governor of Punjab, was gunned down by his own bodyguard. Taseer and his bereaved family did not receive even half the protocol which was noticeably received in Shahbaz Bhatti’s royal state funeral. In addition, Shahbaz’s brother Dr. Paul Bhatti, out of the ordinary and immediately, was compensated with a newly created position of advisor to the Pakistani Prime Minister. Such a position alone pocketed him over 2.5 million rupees besides other governmental perks. However, he only met the Prime Minister just a few times during his tenure, so what advice was he actually good for?

Sources have revealed that Shahbaz Bhatti was married to a woman, known as Salma Peter John, who admitted to being his wife in front of the Joint Investigation Team during the interrogation. In a clear and determined voice, Ms. John explained how intelligence agencies had constantly been following Bhatti, who was also known as Cammy to her, a nickname which was derived from his first name, Clement.

In November 2003, Shahbaz Bhatti was briefly placed on Pakistan’s Exit Control List to ban his overseas travels. The restriction was lifted after Bhatti was able to raise international hue and cry. Ms. John reports that later, someone by the name of Mr. Shah would regularly call Cammy to find out who he met on his overseas trips. I could recall a time, when he was summoned to the office of one of the governmental intelligence agencies. He wrote a will before leaving our house at I-8/3. I read his will myself in which he advised his workers to continue his struggle in case he did not come back alive after such interrogations. When he returned, he was very sad and totally wiped out emotionally. Just before his death, he would talk to me for an unusually long time late at night, expressing his deep fear that he would die before me, a reference to their marriage vow in which the two of them had vowed to live and die together.

Bhatti was sworn in as federal minister of minority affairs in November 2008. In December 2010, however, his ministry was devolved from the federal level to the provincial level, a down-sizing insult which Bhatti was not willing to accept. Vocal as he was, he registered his complaint along with five other sympathizing parliamentarians to the then Prime Minister of Pakistan, Yousaf Raza Gilani. At that time, he also activated international support once again for himself, emphasizing the need of a federal ministry for minority affairs.

On February 3, 2011 on his last overseas trip, he attended the Presidential Breakfast in Washington, DC, subsequently meeting Hillary Clinton, the then Secretary of State. He continued his trip onwards to Canada and was able to make inroads with the Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper. Pervez Masih, the then president of the International Christian Voice, who was accompanying Bhatti, recalls his meeting in Ottawa and the visible perturbation and wrath of the two Pakistani officials who followed Bhatti.

When Shahbaz Bhatti returned to Pakistan in mid-February, 2011, he was readily sworn back into his office as federal minister of minority affairs, but the writing on the wall had already been written. Daily Jang had published the news that Shahbaz Bhatti is on the top of the hit list of the Taliban. Surely enough, on March 2, 2011, Bhatti was gunned down in an assassination purportedly carried out by non-state actors.

Three years after Shahbaz Bhatti’s death, though admittedly his brothers have tried hard to pursue justice, they have started getting death threats themselves, as if a hidden third hand were telling them, You have received the blood money for your brother’s murder. Now hush up.