Who will listen to the tale of my woeful heart?

Far and wide have I wandered on the face of this earth

And I have much to impart

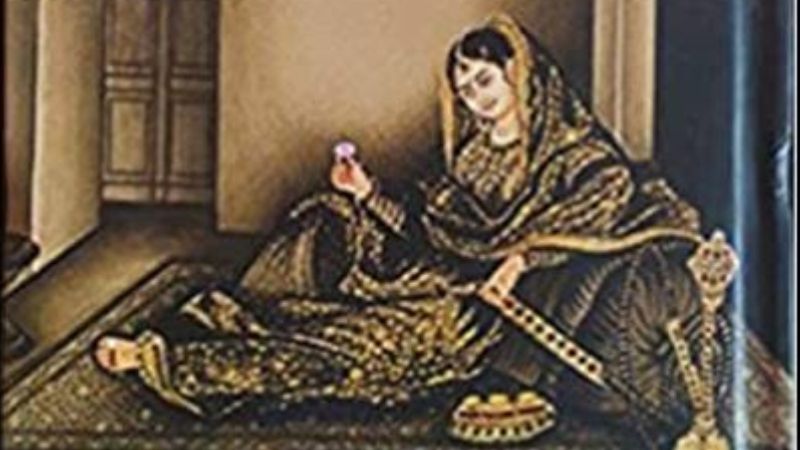

It is not a coincidence that the earliest novels of the Subcontinent dealt with the intense and memorable characters of ‘nautch girls’. Essentially a colonial construct, a nautch girl referred to the popular entertainer, a belle beau who would sing, dance and, when required, also provide the services of a sex worker. The accounts on the marginalised women from the ‘dishonourable’ profession are nuanced, concurrently representing the duality of exploitation and empowerment.

Long before feminist discourse explored and located the intricacies of sex workers’ lives and work, male novelists during the 18th and 19th centuries were portraying the strong characters of women in the oldest profession. Stereotypes of the hapless and suffering prostitute rarely find mention in texts from that time, but one early novel, written in Urdu, is Mirza Muhammad Hadi Ruswa’s Umrao Jan Ada. While the Lucknow-based poet Ruswa is said to have persuaded Umrao to reveal her life history, many critics have surmised that the narrative was authored by Umrao herself. The tone and candour of the story suggests that Umrao played a significant role in drafting this semi-documentary piece.

Umrao’s woes originated in a typical patriarchal mould. As a young girl, she was kidnapped by a hooligan and sold to a Lucknow kotha (a high-culture space also operating as a brothel) managed by Khanum Jan. This act was the hooligan’s way of seeking revenge against Umrao’s father, who had testified against him. At the kotha, an erudite, elderly maulvi transformed Umrao into a civilised poet-cum-entertainer, educating her in the arts and culture. Her seeking knowledge and acquiring confidence to handle a predominantly male world takes place within this space. Thus, the tale of exploitation turns into a narrative of self-discovery.

An archetypal courtesan steeped in Avadhi high culture and manners, Umrao Jan Ada comes across as a voice far ahead of her times. In her frank conversations with Ruswa, Umrao explains how a sex worker’s only friend is money. The realisation that a dancing girl would be a fool to jeopardise her livelihood by giving her love to a man was a clear expression of her empowerment. The plain rejection of wifehood in Umrao Jan’s worldview was directly rooted in the decision not to trade independence for an institutionalised relationship, despite the respectability that such an association might offer. The empowerment of Umrao is in many ways linked to her profession. In an age where women were completely dependent on men for financial and social sustenance, sex work emerged as a safety valve for her existence. And Umrao remains contemptuous of courtesans who leave their position of power and independence, and subject themselves to the whims of respectable men who may or may not reciprocate by according them social respect.

The novel also chronicles the disruptions caused by the deepening of colonial rule, and Umrao is quick to recognise that her survival is linked to the British. She witnesses the destruction of Lucknow, which was at the centre of the 1857 Mutiny and the subsequent crackdown by the British, recording how her kotha was destroyed. Resignation as well as proactive adjustment to political and social changes is a theme that runs across the book. Towards the end of the novel, Umrao is not only a thoughtful woman but also a stronger one – neither fatalistic nor depressed about her life. For its robust yet ambiguous portrayal of characters and vivid glimpses of mid-19th-century Uttar Pradesh courtesan culture, Umrao Jan Ada remains a great novel straddling the layers between the empowerment of a woman and her exploitation. The female characters in particular come alive on the page – Khanum Jan, the kotha madam; Bua Hussaini, a housekeeper in her old age; and Umrao’s contemporaries, Bismillah Jan and Khursheed.

Avadh novel

Prior to Umrao Jan Ada, another Persian text, Fasana-e-Rangeen (1790), translated into English as The Nautch Girl in 1992 by Qurratulain Hyder (and translated into Urdu as Nishtar in 1893), is arguably the first novel of the Subcontinent. This autobiographical novel by Hasan Shah narrates the story of an East India Company munshi (clerk) and his doomed love for a dancing girl, Khanum Jan. While in the service of the Englishman Ming Saheb, in Cawnpore (Kanpur), the young Shah spots a beautiful dancing girl in a visiting troupe under the patronage of the English saheb. Ming Saheb also lusts after Khanum Jan, the femme fatale, who rejects his advances. Ming then shifts his attention to another member of the troupe while the confident Khanum Jan falls in love with the lowly clerk. The story is likely an autobiographical one. Eventually, the starry-eyed lovers enter into a secret marriage. Jan, however, leaves Cawnpore with her troupe when the English officer is transferred and his patronage ends.

The hallmark of this novel is the portrayal of Khanum Jan, who appears as a confident, educated and strong-willed character. Her ability to say no to a gora saheb and her subsequent subversion of her place in the troupe by secretly marrying Shah are remarkable for 18th-century India. Even though Khanum vowed not to be a courtesan all her life, she does not leave the troupe. Though not as empowered as her successor, Umrao, Khanum Jan is cognisant of her social position and responsibility as an employee. While this remains a simple story of love in times of change in India, the nuances of human behaviour portrayed announce the arrival of the Indian novel. It is noteworthy that the heroine of the ‘first Indian novel’, to use Hyder’s phrase, happens to be a dancing girl.

Avadh (Oudh, later the United Province) state, formally annexed by the British in the mid-19th century, was a hub for the political and social transformation of India. Amid these changes, the voice of dancing girls is distinct, reasoned and powerful. To echo Hyder, the case of Oudh reminds us of the famous verse by Edna St Vincent Millay:

My candle burns at both ends

It will not last the night

But, Ah my friends and Oh my foes

It gives a lovely light

As Hyder puts it, Oudh was India’s Camelot, where Khanum Jan becomes the torchbearer of an emerging high culture; and Umrao Jan, like a burnt candle, narrates its denouement. Umrao, in the twilight of Oudh culture, reflects the realisation of empowerment within the patriarchal fold. It should be remembered that Hazrat Mahal, the wife of the last ruler of Oudh, was also a dancing girl, and issued a farman (edict) defying the British and declared that the state had nothing to do with religion. The blurred boundaries between warriors, sex workers, rulers, poets and entertainers was informing the public imagination thus leading to a repositioning of dancing girls in Victorian India.

Berating the shuraafa

A legendary Urdu writer, Hyder remained fascinated by the various permutations of the Indian nautch girl throughout her literary career. In her later novel Gardish-e-Rang-e-Chaman, a semi-documentary work, she blurs the boundaries between the respectable and the non-respectable. It is historically recorded that Mughal princesses orphaned after the anti-Mughal killings by the British caused a major upheaval in the comfortable zones of Muslim rule in India. The central character of the novel, Nawab Begum, is one such descendent, who later becomes a courtesan. After a long career, she revels in her status as a powerful woman. In the true tradition of courtesan lineage, Nawab Begum launches her daughter as a theatre performer in early-20th-century Calcutta. The textual tenor moves between the context set by Ruswa, between the pathos of exploitation and the energy of empowerment.

In this novel, published in 1987, Hyder’s Begum is a fictionalised portrayal of Gauhar Jan, also an early-20th-century singer from Calcutta. (An excellent book on Jan, My Name is Gauhar Jan, by Vikram Sampath hit bookstands earlier this year.) The mother-daughter duo became the best-known bais (singing women) of Calcutta. Based on this formidable reputation, Frederick William Gaisberg, the Gramophone company’s first India agent, selected Gauhar in 1902 as the first Indian artiste he would record. Popular culture’s interface with modernity in India came about through these empowered, singing women. With her cosmopolitan vision and command over several languages, Gauhar was a trendsetter, a flamboyant star long before Bollywood adopted glitz as a policy.

Another celebrated Urdu author to explore societal attitudes to sex workers with a surgeon’s precision is Saadat Hasan Manto. After the hypocrisies and mayhem of 1947, Manto started viewing sex workers as finer human beings than the religious shuraafa, the ‘honourable’ people usually from the upper middle classes. One such memorable character is that of a Jewish sex worker in Bombay called Mozail. Against the backdrop of the 1947 riots, Manto portrays the innate humanity of Mozail as she parades naked, getting killed in the process, to distract a rioting mob and rescue individuals.

Meanwhile, the new nation states formed following 1947 and 1971 have been unable to define clear approaches towards those engaged in sex-related professions. If anything, the Victorian colonial state inherited by the newly independent nations has defined public morality and ‘righteous’ conduct. Inevitably, the voice of the sex worker is lost in the regulatory framework imposed from above. In the morally charged post-colonial societies, courtesans of yore have found other avenues. For instance, due to General Zia ul-Haq’s Islamisation and the attempt to ‘clean up’ brothels across Southasia, sex workers have moved and integrated into the mainstream social fabric. In Pakistan, Lollywood, the Lahore film industry, has absorbed a large number. After the decline of the film industry in recent decades, commercial theatre has become the new playground for the exploited-empowered courtesan. One such theatre company in Pakistan’s cultural centre, Lahore, pays PKR 2 million per month to a theatre actor whose identity as a sex worker is now blurred with other labels. The rise of massage parlours and private services via the Internet and the advertisement chain has further compounded the notion of sex work and stripped it of conventional labels.

Ghulam Abbas’s Urdu short story Anandi (also made into a classic film Mandi by the filmmaker Shyam Benegal) remains a parable for times to come. The moralistic municipality of an imagined city expels sex workers and brothels to improve public morality. The sex workers’ abode soon turns into a new city – Anandi – and the land mafia, the trader-merchant class, dargahs and temples spring up in a short span of time. The story ends with another irony:

The meeting of Anandi’s Municipal Council is at full boil, the hall is packed nearly to bursting, and contrary to normal not a single member is absent … One eloquent scion of society is holding forth: “It is simply not known what the policy might have been on the basis of which this polluting class of people was given permission to live in the precise center of this ancient and historical city of ours…” This time, the area selected for the women to live in was twelve kos from the city. Anandi was written in 1939. In certain regards, precious little seems to have changed since then.

Published – HIMAL SOUTHASIAN