July 15, 2018: Nawaz Sharif’s Dilemma: On the Edge

PAKISTAN’S thrice-elected prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, has entered a decisive and somewhat unexpected phase of his career. As a protégé of the Pakistani state, especially its powerful military establishment, Sharif enjoyed patronage and support for decades that enabled him to rule the country’s largest province as chief minister and later as PM.

On July 5, Sharif was sentenced to 10 years in prison with a fine of eight million pounds. The verdict was not entirely unexpected. It was widely anticipated that he would be sentenced for corruption.

Sharif ’s daughter and likely successor, Maryam, along with her husband, Muhammad Safdar, were also sentenced. The anti-corruption court has also ordered the confiscation of the Sharif family’s four apartments at Avenfield House, London.

For Maryam, this verdict was a major blow as it ends her immediate chance of holding office. She was due to contest elections from a safe seat in Lahore, the capital of Punjab province and Sharif ’s stronghold. Maryam, in the past one year, has emerged as a fiery leader in defending her father’s quest for civilian supremacy.

The verdict came 20 days before Pakistan’s forthcoming elections. So, it is in essence, a political verdict where court decrees are being used as instruments to keep Sharif and his party, the Pakistan Muslim League—Nawaz (PML-N), out of power. The PML-N had been leading the opinion polls until recently. With its key leaders sentenced and disqualified from the race, the voters may just give up.

As accidents of history take place, Sharif got into a confrontation with his erstwhile masters when he discovered that as a civilian head of the Executive he couldn’t exercise his due powers. Not that Sharif was an exemplary PM, but he had a raw vision of Pakistan that should focus on economic growth, trade, connectivity and peace with the country’s arch-rival, India. It was the latter plank of his policy vision that brought him into direct conflict with the military establishment and the rest is history.

In 1999, Sharif was ousted in a coup and sent into exile for eight years. He returned in 2007 after the military dictator, General Pervez Musharraf, was facing public protests.

Sharif emerged as the national leader after Benazir Bhutto’s assassination and in 2013 he won a landslide victory that returned him to power. He had vowed before the election that he would bring Gen Musharraf to book and right after taking over the reins of power, his government initiated a treason trial against him. This decision sparked a series of events that ended in his ouster in 2017.

Ostensibly, Sharif was tried for corruption after the release of the Panama Papers which revealed that his family had offshore holdings and held vast amounts of wealth overseas, some of which allegedly may have been laundered. His opponents took this opportunity to pursue the case in the courts and finally, the Supreme Court disqualified him from holding public office. The judgment of the Court stated that the case needed to be tried in an accountability court but due to a technicality (of not declaring a receivable income that was not received though), Sharif was no longer sadiq(truthful) or ameen (righteous) under the constitution. Later, the Supreme Court also barred Sharif from holding a party office and decreed that he had been disqualified for life. Sharif and his party have been criticizing the courts openly and the duel has turned personal between a hyperactive, populist chief justice and the House of Sharifs. In criminal law, the burden of proof is on the prosecution, and if it discharges such a burden, the accused is required to satisfy the court as to why he should not be punished. The prosecution was required to prove that the Avenfield properties in London were, in fact, owned by the Sharif family and their sources of income. Once this was done, the prosecution ought to have shown that the known sources of income were not sufficient to acquire the Avenfield properties.

But this settled legal principle was not adhered to. The judge admitted that proving ownership was complicated, especially when offshore companies were involved. Yet, he decreed that such a burden had indeed been discharged.

The judge highlighted links between the Avenfield properties and Sharif ’s children, whilst finally concluding that at least one of the children was in possession of the flats in question. The judge proceeded on three counts to conclude that ownership had been proven – third party documentation from Mossack Fonseca stating that Maryam Nawaz appeared to be the beneficial owner of an offshore company which owned a part of the Avenfield properties; the UK High Court proceedings in which these properties were attached and interviews of Hussain Nawaz, Sharif ’s son.

This trial had been conducted under the orders of the Supreme Court. It should be noted that the Supreme Court does not have any direct jurisdiction over such a court, but in the extraordinary Panama judgment, this provision was kept for speedy justice.

Action shifts to Adiala Jail

Days after they were sentenced to serve jail terms of 10 and seven years, respectively, for their alleged role in the Avenfield properties reference, former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and his daughter, Maryam, flew into Lahore from London after a layover in Abu Dhabi aboard an Etihad Airways flight at around 8.45 pm. The father-daughter duo were arrested by National Accountability Bureau (NAB) officials upon arrival and whisked away to Islamabad on a chartered flight.

At Islamabad airport, Nawaz and Maryam were separated and taken in two convoys to the Central Jail in Adiala, Rawalpindi, for a medical examination. An NAB prosecution team approached the accountability court seeking an exemption for the duo’s appearance before it citing security risks – a requested readily granted by the court. The move checkmated the former premier’s plan of playing the victim in an open courtroom and galvanising his party workers ahead of the July 25 general elections in Pakistan. The trial of two remaining NAB references against the Sharif family will now take place in Adiala Jail.

The court said that in the absence of relevant documents to disprove ownership, the presumption was that Nawaz Sharif was the true owner of the properties. As a Pakistani lawyer, Basil Nabi Malik, noted: “The haphazard, hasty and rushed manner in which the judgment was given, its timing and the constant interventions from the Supreme Court give an overall impression of justice being hurried, and ultimately, buried.”

Pakistani jurisprudence requires that a convict who is “fugitive from law is not entitled to invoke the provisions of S.32 of NAB Ordinance to challenge conviction”. This is why Nawaz Sharif and his daughter have decided to return to Pakistan and file an appeal. Many legal experts have said that this judgment is a weak one and, therefore, could be set aside. This is what makes the Sharifs a bit hopeful, at least, on the legal front.

But given that law and politics here are intertwined and inseparable, a key purpose of Sharif ’s return is also to energise his party support base before the July 25 elections. With him and his successor, Maryam, in jail, there is likely to be a sympathy wave as well as some measure of anger (that can be witnessed on social media postings) among their supporters.

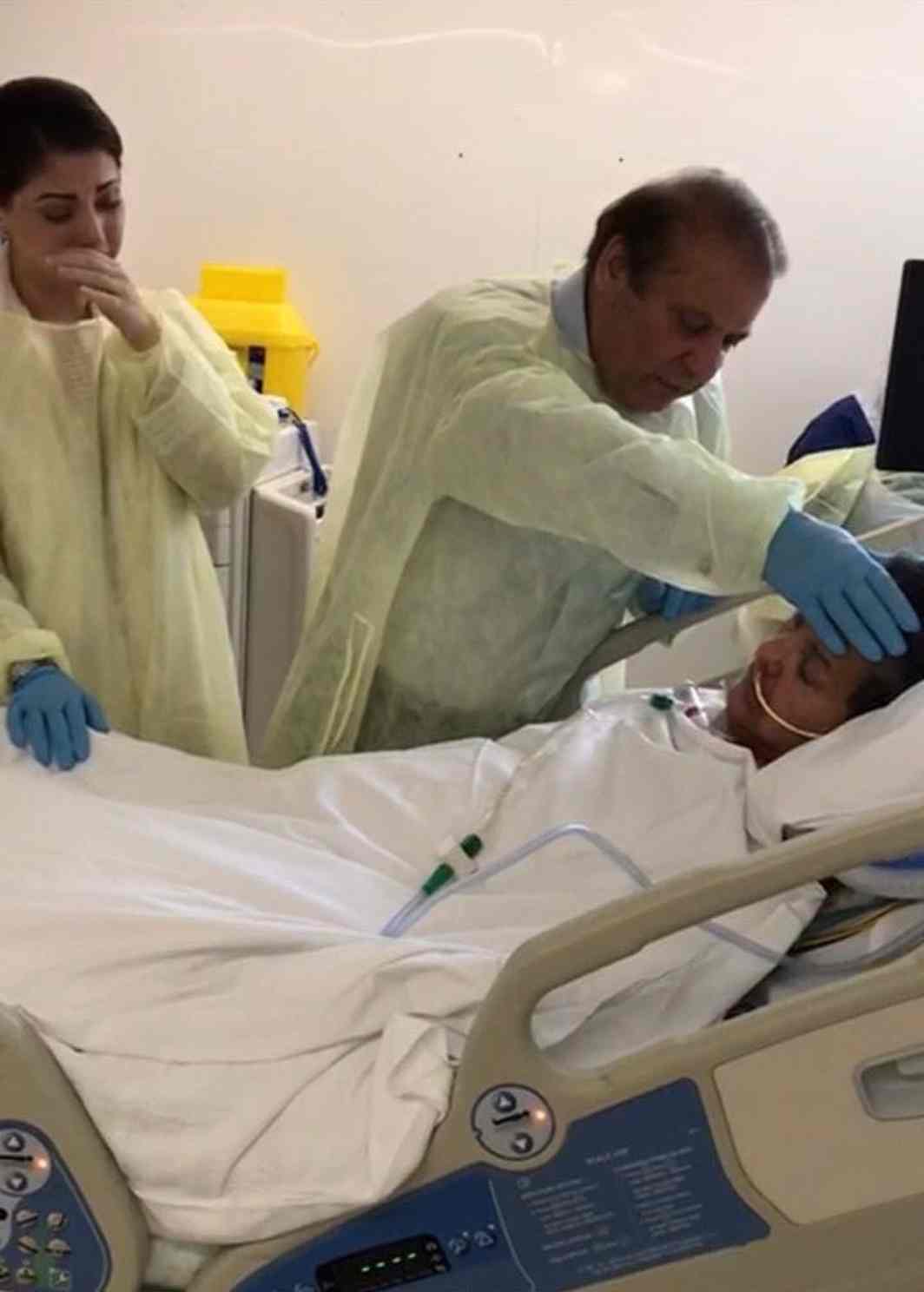

Nawaz and Maryam bid adieu to a comatose Kulsoom at a London hospital; Kulsoom reportedly came out of coma two days after they left for Lahore/Photo: Twitter

It is not going to be an easy ride. Sharif ’s main rival, Imran Khan, is already making gains in the electoral arena. Khan enjoys the patronage of sections of the establishment and Pakistan’s media, and also has considerable following in urban centers. He has also accepted turncoats from Sharif ’s party and the other large political force, the Pakistan People’s Party.

Khan’s supporters view the corruption sentence as a victory and a validation of their struggle against corruption. This is the complication with Sharif ’s politics. On the one hand, he represents all that is wrong with Pakistani politics, and on the other, he is also the defiant anti-establishment figure now. Pakis – tan’s elites including political party heads have amassed enormous amounts of wealth that have partly been possible due to their access to state levers and the ability to influence policy.

Given the severity of sentences for the Sharif father-daughter duo, immediate bail is also not on the cards. The two will have to be in jail, at least until the appellate court, in this case the Islamabad High Court, admits the appeal. This protracted legal battle will continue.

Sharif is not the only political leader that has faced corruption cases. Late Benazir Bhutto (also PM twice) and her husband faced corruption charges through much of her career. From 1990- 2017, her husband Asif Ali Zardari faced dozens of cases and spent more than 11 years in prison. Most of the charges could not be proved. Zardari served as president from 2008 to 2013.

Last week, a major money laundering scandal broke out that implicated Zardari. Subsequently, the federal investigation agency and the Supreme Court also summoned him. The message was clear. If he and his party were not going to adhere to the establishment’s playbook, they could face the accountability music.

The use of corruption charges is not a new instrument. It has been in vogue since the 1950s when Pakistan’s first military dictator Gen Ayub Khan framed laws to “disqualify” elected officials. A large clean-up process was undertaken through the decades to ensure that the civil-military bureaucracy could continue their dominance over the political landscape.

Ironically, Sharif too had employed a witch-hunt against Benazir Bhutto’s party during the 1990s. The accountability commission that he set up was brazenly used to squeeze his political opponents. One is not sure if he regrets doing all of that, but he certainly is aware of how accountability and anticorruption slogans are used to kick foes out of the political arena.

Decades later, Sharif faces the same predicament. This is how the wheel of history has moved full circle. But this time, it is different because Sharif is the first popular politician from Pakistan’s largest and most powerful province, Punjab, who is at the receiving end of the civil-military establishment.

This summer will be dramatic and may reset Pakistan’s direction. Even if Sharif ’s party does not rise to power, its presence in the political system will be a reminder of a changing Pakistan—one that values civilian supremacy and exorcising the ghosts of the past.