Pakistan’s decade-old democratic transition is going nowhere. Ten years after the military president Gen Musharraf removed his uniform and paved the way for national elections, we are back to square one. Worse, the defective democracy today resembles the decade of the 1990s where political elites were scrambling for power in cahoots with the military establishment with disastrous consequences.

The future trajectory of this transition remains an open question.

In 2007, the lawyers’ movement and the decision by the junta led to a historic return of democratic rule. The key political players — the Pakistan People’s Party and the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) — had agreed on the (now defunct) Charter of Democracy with the express vow that they would not allow the establishment to derail the democratic process. Both parties successively sabotaged it and the third major player Imran Khan was never a signatory to the Cod and by 2013 this compact was all but dead.

The political elites did restructure the governance arrangements through the 2010 eighteenth amendment to the Constitution but they fell short of undertaking four major reforms. First, the required legal and institutional changes to streamline how the deep-state works. Second, no major party was serious about judicial reform. The restoration of Justice Iftikhar Chahudry to the Supreme Court was seen as an end and not just a means to restructure how the judiciary worked. Thirdly, no major headway was made in terms of electoral and political party reform. Instead, political parties were turned into leader driven entities with no internal democracy. Finally, parliamentary input into governance, especially foreign and security policies, remained weak or non-existent thereby leaving these two areas with the military and its intelligence agencies.

Consequently, we have two Prime Ministers fired by the Supreme Court on tenuous grounds and even today a shift in foreign policy goals with respect to India, Afghanistan and the United States constitute ‘treason.’ Two decades ago, Benazir Bhutto was the security risk and now Nawaz Sharif is painted as a ‘sellout.’ Even more alarming is that 27 years of the Benazir-Zardari accountability merry-go-round is now giving way to another farce: holding the Sharifs ‘accountable’ for their unexplained wealth. If the earlier experiment is any guide, the fate of the Sharifs’ accountability drive is not going to be too different.

Political instability will continue to prevent formulation of long-term policies that Pakistan urgently needs to face impending water scarcity, effects of climate change, finding jobs for young people and sending millions of kids to school

The manoeuvring of the military establishment notwithstanding, the key political players cannot escape responsibility. Nawaz Sharif treated the Parliament as a rubber stamp and invested little in strengthening the civilian institutions. The PPP co-Chairperson Zardari has been in perennial bargaining mode since his party was voted out in the 2013 elections. And Imran Khan has clearly been playing the game, the rules of which are set by the establishment. Like many others, Khan understands that the road to power passes through the barracks. Just the way Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif ascended to the Islamabad throne.

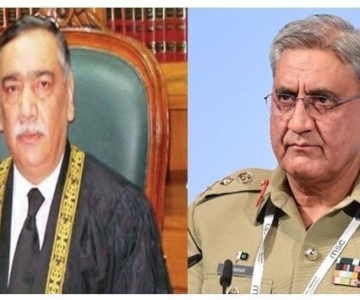

A decade after Gen Kayani decided to return to the barracks and exercise authority from the backseat, the junta, aided as always by the judiciary, seems to be working on a new political engineering project. The immediate objective is to remove their nemesis Nawaz Sharif from the political scene. Herein lies the irony of our times. Nawaz Sharif appears to be the only anti-establishment figure and projecting a transitional posture as a future ‘deal’ may make him change his stance.

The rest of objectives of the engineering underway remain clear. The embarrassing saga of establishment-sponsored alliance of two factions of the erstwhile Mutthihada Qaumi Movement (MQM) hints at both cutting into the PPP’s hold over Sindh province. The revival of the Musharraf-era alliance of religious parties (some of whom will not pray together let alone share an ideology) points towards gaining more ‘favourable’ results in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan if and when the elections are held in 2018. Two extremist groups — Jamaat-ud-Dawa and Tehreek e La Yabak — have already entered the electoral fray and are preparing to expand the adhoc militants’ mainstreaming project. The next development on the cards is the fragmentation of PMLN that would ensure that it does not emerge as the single largest party in the next election. The recent activation of an old corruption case against the Sharif brothers and the detailed judgment of the Supreme Court indicate that the two pillars of the state mean business.

In case all of this does not deliver, the postponement of elections due to delimitation of constituencies based on the new census results is another option to exercise. The only silver lining here is that unlike 1958, 1969, 1977 and 1999 a direct military takeover seems to be the least preferred option.

Both Sharif and Zardari are old hands at politics. They can read the signs. Imran Khan has been around in politics for decades. But all three are at loggerheads. Zardari and Khan are keen to collaborate with the establishment for their share of the power pie. We are officially back to the politics of the 1990s. And we mustn’t forget how that decade-long experiment in quasi-civilian rule ended.

It is clear that neither the establishment nor the political elites have learned any lessons from the past. Political instability will continue to prevent formulation of long-term policies that Pakistan urgently needs to face impending water scarcity, effects of climate change, finding jobs for young people and sending millions of kids to school.

Published in Daily Times, November 12, 2017: Pakistan’s democratic transition is derailed. Does anyone care?