by Vidya Rao

I was fortunate to be one of the women invited to the first meeting of the Grandmothers’ University at Bija Vidyapeeth early this year. The Grandmothers’ University hopes to save the endangered traditional wisdom of women, and make possible a space where this wisdom can be shared with others. I was invited to speak about the wisdom of the traditional women singers of north India.

I am a singer of the traditional north Indian classical musical style called thumri. Like many women of my generation, as a student, I was encouraged to learn the more ‘respectable’ form of khayal for thumri had traditionally been sung by courtesans, and as such, both performers and form were then viewed with some suspicion. (Much of this has, thankfully, changed.) My taleem of, and research into this song-style led me to several traditional performers retired and elderly courtesans– apart from my own teachers who were all pioneers in bringing thumri out of the shadows. Speaking with them, learning from them, watching them perform, I learnt much about music, but also about life.

Thumri is different from the more mainstream form khayal in its emphasis on the poetic text of the song (other forms of classical music tend to be more abstract), and its focus on the emotional universe contained within the poetic text. The style of singing requires the singer to identify totally with the protagonist of the song ( invariably, a woman the nayika) The courtesan’s performative style directs the song to her (male, elite) audience, inviting these, her patrons, to become the one addressed in the song. It is a form therefore that is at once musical, conversational, dramatic and even dancerly (the traditional performers would dance as they sang’a style that one rarely sees now). This also makes the form intensely emotional, but also very light and playful. The technique of singing requires the singer to take each phrase of the poetry and sing it in different ways ( bol banao), with different emphasis (kaku) and even to slide in and out of ragas ( avirbhav-tirobhav); this heightens the sense of the dramatic and of the emotion experienced by the nayika of the song. While the lyrics are invariably romantic, thumri’s singing style encourages inflecting the song and pulling it towards the devotional, even the philosophical, making it also thus highly layered, multivalent.

For the meeting of the Grandmothers’ University, I decided to focus on how the songs of the courtesans and their singing style led me to a quite extraordinary sense of self, of body, and gave me a different perspective on youth and beauty. My concern was more specifically with how thumri’s romantic songs, that invariably speak of the young, beautiful nayika, when sung by elderly women well past their prime, actually give us new and powerful insights into our selves and our bodies, beauty and ugliness, life and death.

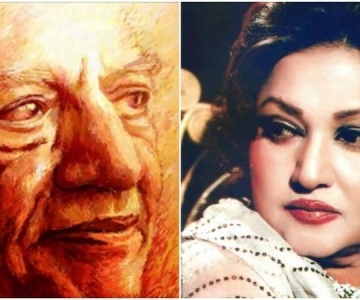

I remember here, a moment in my life with my first teacher of thumri the legendary Naina Devi , a woman, who, born into an elite Bengali family, nevertheless defied convention to become one of India’s leading singers. In sharing this moment now, I hope to communicate some of the magic and wonder of that insight and understanding.

In the last years of her life, Naina ji seemed to go back to her childhood in Kolkata, speaking Bengali rather than Hindi, eating Bengali food and often singing Bengali songs. I remember one Shyama Sangeet songs in praise of the goddess Kali, who is also known as Shyama (the Dark One):

Shiva’s matted locks

Ram’s neatly coiled hair

Shyam’s crown adorned with a peacock feather

But my Shyama’s hair is wild and free.

In Ram’s hand, a bow and arrow

In Shiva’s his trident

Shyam holds his winsome flute

In my Shyama’s hands, a hideous skull.

Ram, resplendent in a king’s robes

Shyam, radiant in his yellow pitambar

Shiva wears a tiger’s skin

But my Shyama is clothed in nakedness.

Naina ji teaches me this song, and she tells me how, as a child, she first heard this song in Banaras from a beggar-woman named Khendi.

Khendi was ragged, sickly and quite hideous. Her skin was rough and scaly, covered with sores. Her pockmarked face had caved in she had no teeth and her nose had been devoured by disease. Khendi claimed she had been a courtesan-singer once. And you could believe that when you heard her sing.

She would come to the house to beg for food, clothes, moneyand the occasional cigarette. ‘Just one cigarette,’she would whine or else, smacking her lips, remembering perhaps, sumptuous past meals, she would wheedle ‘An omlette, please, for hungry Khendi!’

Then she would sing this song in response to Naina ji’s request.

When she sang she was not Khendi the beggar-woman. You forgot her strange, broken face, her rags and tatters. There was only her voice, only the music, only the presence of Kali.

As Naina ji speaks, as she sings, I seem to hear Khendi rich, sweet voice singing this song set in the raga Khamaj. Khendi sings as if she has traversed the pathways of that lovely raga many, many times; she knows Khamaj as a mother knows the body of her baby. And she travels Khamaj’s landscape without map or compass, without accompanists or instruments, fine clothes, jewellery or listeners. As Naina ji speaks, Khendi is here I hear her sing, I see her. And as Khendi sings, the great Goddess stands before me in all her terrible beauty. Is this the Goddess or Khendi?

And then I understand that Kali’s terrible image must be sung into being with tenderness and love. Kali’s form, her bloody tongue, her staring eyes, the skull in her hands, her home in the cremation ground — these are her shringar, her adornment, her beauty.

Listening to Naina ji’s story, singing those songs sometimes celebrating the young and beautiful nayika, sometimes honouring the terrible Dark One– I realize, with a burst of wondering joy, that beauty and ugliness are but mirror images of each other, as are passion and renunciation, life and death, shringara (love) and bibhatsa(disgust) and bhayanaka (fear). And I realize too that it is music, the flowing river of raga, that enables me to travel from one apparent extreme to the other and to know them to be one in essence.