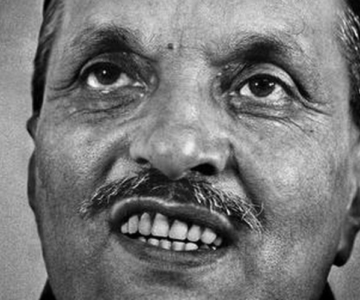

The anniversary of General Zia-ul-Haq’s 1977 coup is a particularly difficult time for the Pakistani democrat. The very name given to the coup sounds much like a sardonic smirk echoing through history from the dismal gentlemen in uniform who carried it out: Operation Fair Play. The remembrance of what came after that fateful 5th of July remains painful – for in many ways we are today as utterly helpless as we were all those decades ago in the face of that which General Zia unleashed upon Pakistan and its people.

What is it that made General Zia’s time in power so particularly harmful and traumatic for the country? It can be argued that he simply picked the worst strands already present in Pakistan’s history and institutionalized them to maintain his power. This was all done with ruthless disdain for the country’s destiny. The official version of Pakistan’s past, present and future became a dark and dreary dystopia.

Let us go over the three main wounds that were inflicted upon the Pakistani body politic by the General.

First, and most obvious, the coup cemented the idea that constitutional democracy came at the very end of a long list of other priorities in Pakistan. The parliament elected in 1970 was the very first elected on the basis of universal adult franchise. The controversial elections of 1977 and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s flawed policies were no excuse to end democratic rule in Pakistan – or what was left of it after 1971. That and the subsequent judicial murder of elected Prime Minister Bhutto meant that it would be difficult to establish viable civilian democratic institutions in the country for decades to come. And sure enough, the precedent set by General Zia allowed for what General Musharraf did only a decade after the former’s death. Moreover, the very potent threat of unconstitutional putsches and coups continues to haunt the democratic process in Pakistan today. It must not be forgotten that today, just as in 1977, there are political parties and leaders who openly call for yet more intervention in political disputes from unelected and unaccountable institutions of state.

Second, the coup enabled General Zia’s regime to tie Pakistani foreign policy so intimately with armed non-state actors that today’s civilian and military leaders, even with the best of intentions, cannot easily change course. Contemporary Pakistan stands in a disastrous diplomatic position vis-a-vis at least three of its neighbours in both its east and west. The contours of General Zia’s strategic thinking can still be clearly seen in our predicament today.

Third, perhaps most unfortunate, was the wholesale mutilation by the Zia regime of Pakistan’s social fabric and religious discourse. The policy which the General called “Islamisation” led to anything but that outcome: it simply gave unprecedented and previously unimaginable power to cynical religious leaders who combined stubborn conservatism with virulent fundamentalism. This understanding of religion and its place in Pakistani society permeated every aspect of life, beyond the overt political sphere. The educational sector, spirituality, sciences, arts, culture, languages, clothing, tastes and consumption patterns of Pakistanis were refashioned during the Zia era to fit into a fundamentalist mould. Today, as Pakistani society struggles desperately in its search for a “counter-narrative” to the violent lunacy of the Taliban and the Islamic State group, it is inevitable to trace the difficulty back to the genies unleashed deliberately and methodically during the 1980s.

In short, General Zia-ul-Haq was far more than a mere dictator looking to perpetuate his power. What he unleashed was a wholesale project of right-wing social transformation. Each of the three wounds described above, far from having healed, remains raw, fresh and ready to burst open.

On this 5th of July, Pakistan’s state and society continues to slog through the desert of authoritarianism, militarism and fundamentalism where Zia-ul-Haq led it.

Published in Daily Times, July 4, 2017: The unhealed wounds of July 5, 1977