The year 2012 will be remembered for a fragile democracy that continued to consolidate itself amid regional instability and belligerence of unelected institutions trying to assert their waning powers.

The year began with the brewing tensions on the memo affair whereby the military-intelligence complex had accused Pakistan’s former ambassador to the United States, Husain Haqqani, of seeking US intervention should there be a coup in Pakistan.

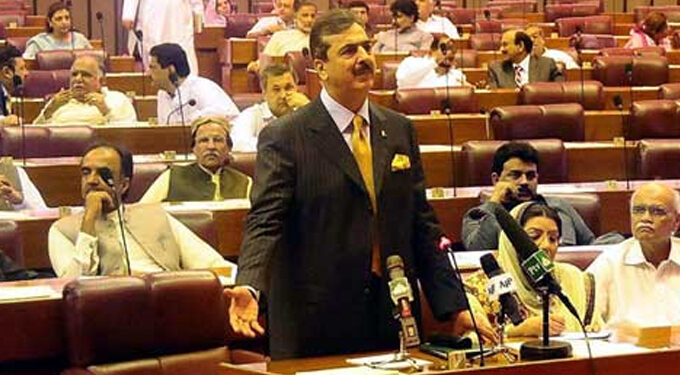

During late 2011, the Supreme Court was moved by the opposition leaders to take cognisance of this drummed up ‘national security’ issue. In the wake of the mounting pressure the former Prime Minister, Yousaf Raza Gilani, delivered his famous remarks where he complained of a ‘state within the state’ operating in Pakistan.

This tension set the course of events to follow. Unelected institutions – the military, intelligence agencies, judiciary and the media – dominated the national scene and constructed how democracy was viewed and the performance of the civilian governments at centre and provinces was assessed. The memo affair took a new turn when media reports emerged that the then-chief of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) had undertaken a tour of Muslim countries allegedly to build support for a coup d’ètat in Pakistan.

Such unverified reports exerted pressure on the military and it decided to backtrack and settle for the dismissal of the ambassador. A commission formed by the Supreme Court released its report which sadly regurgitated the petitioners’ point of view as well as the notion of ‘national security’ popularised by the state since the inception of Pakistan.

Matters became heated with the judiciary once again when charges were made against the sitting prime minister and, after a dramatic hearing, the Supreme Court disqualified PM Gilani. Subsequently, Gilani had to leave office paving the way for another PPP loyalist from the Punjab, Raja Pervaiz Ashraf, taking oath of the PM. The cost of this instability was great.

The federal government remained engaged in defending its president, PM and appointing the new PM instead of focusing on the long-term energy crisis, the economy and other policy issues which require coherent action. The media, instead of highlighting the constructed instability, focused more on the lack of performance of the ruling coalition. The term governance remained in the news but without the contextual understanding, especially that of unaccountable status of the civil-military bureaucracy and the judiciary.

How could governance be responsive when key pillars of the state and those who deliver vital services are beyond the accountability net?

The next half of 2012 was relatively more stable as the government and judges came to an understanding and avoided another conflict over sending a letter to Swiss authorities for reopening old corruption cases against the president. In the process, a letter was sent and the court implicitly accepted the constitutional immunity available to the president under the Constitution.

Once this was over, the petitions against the dual offices – as Pakistan Peoples Party chairperson and president – of Asif Zardari came into the courts and there was a renewed focus on this matter despite the fact that there is nothing in the Constitution that expressly bars the president from holding a party office.

Judicial activism continued as the Supreme Court decreed on the volatile law and order situation in Karachi, and the Balochistan situation. In the latter case, it made extraordinary remarks during the proceedings and also adjudicated that the provincial government had failed to deliver according to the constitutional mandates. Political and legal circles criticised this judgment, citing it as another case of judicial overreach. However, the court surprised everyone as it widened the scope of its accountability of the executive.

The military and the intelligence agencies also came under severe criticism in the Balochistan case. Earlier, on the missing persons, the court had asked the paramilitary forces stationed in the troubled province to explain their acts of commission and omission.

The climax of judicial scrutiny of the powerful military was the decision on the Asghar Khan case where the court held that the former Army chief, Gen Mirza Aslam Beg and his colleague, then-ISI chief Lt. Gen Asad Durrani, had rigged the 1990 election. This is a major victory for civilian ascendancy as the well known truths in the unofficial domain are now legalised by a formal court order.

Sadly, not much has happened on the implementation, as the sitting government neither wants to annoy the military nor its chief opponent Nawaz Sharif who was a beneficiary of the army largesse in the early 1990s.

The court did not remain free of scrutiny itself either. A major scandal involving the son of Chief Justice Iftekhar Muhammad Chaudhry came into public domain through charges leveled by a business tycoon, Malik Riaz. Briefly, he accused the chief justice’s son, Arsalan Iftikhar, of taking favours in lieu of influencing judicial verdicts.

Unnerved, the chief justice held court and presented explanations citing Islamic figures such as Second Caliph Omar (RAA) and swearing on the Holy Quran that he does not know anything about his son’s misdoing. Soon, he transferred the matter to another bench and to date not much has happened in this case. The media wizards broke this story on the social media and later backtracked.

Things came to a collision path when the chief justice and the Army chief, Gen Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, spoke indirectly about their respective institutions, and blamed each other of overreach. The situation calmed a bit but it was clear by the end of the year that the media, army and the judges driven by their institutional interests of power and profits (in the case of media) were no longer united as they were for a good number of years under the PPP government. This has given more space to the maverick President Zardari, who seems firmly in charge.

In December, two events in quick succession have charged the political atmosphere. As Pakistan heads towards general elections, Dr Tahirul Qadri, a moderate cleric, held a mammoth rally in Lahore calling for military and judicial involvement in the selection of caretakers. Qadri also beat the old drums of accountability and electoral reform used by the military to derail the democratic process. Thus far, the major parties – PPP and the opposition Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz – have shown a tacit understanding as major stakeholders of democracy. This makes it tough for the military-intelligence complex to steer the electoral outcomes. It is most likely that given the state of tension between various power centres, there will be no consensus or support that the military has enjoyed throughout our history.

The second key event was the formal [re]launch of PPP’s young Chairperson Bilawal Bhutto Zardari in mainstream politics. His passionate speech on December 27 reinvoked the memories of Benazir Bhutto and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, and energised the sagging spirits of the PPP workers. Bilawal delivered a speech in Urdu that covered all the usual themes and played on the PPP versus the establishment theme. But it was unique for its clarity on extremism and this was both reassuring and worrying.

Reassuring since PPP’s office holders in power have been appeasing the extremists and Bilawal made a departure; worrying, because it also makes him more vulnerable to the militants.

The year 2012 was also the year of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) which continued the acts of terror against Pakistan and its civilians. Its allies, the Sunni extremist groups, added to the mayhem by targeting Shias, including the members of the Hazara community. Hundreds of deaths occurred and the most tragic incident was the murder of Bashir Ahmad Bilour in Peshawar.

Bilour is not the first one to die from the Awami National Party (ANP). The party has lost nearly 800 workers and leaders in the recent years. This political assassination has, if anything, shown the nature of the violent election campaign that we will be entering into. The TTP wants to unravel Pakistani state and its constitution and it does not even spare young children like Malala, who was shot for resisting their diktat on banning girls’ education. While Malala survived the attack, her exit from Pakistan along with her family was the nadir of our collective existence as we cave into the extremists’ logic.

Sadly, many media commentators, political parties such as Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf and Pakistan’s burgeoning youth are confused about the harrowing challenge of extremism. Despite their atrocities, many want the state to talk to TTP and compromise, thereby accepting their power, which in the first place was infused by the Pakistani state itself.

The year ahead will throw more of political instability as none of the parties is likely to emerge as a clear victor in the next elections and there will be a weak coalition sworn in by the end of the year. Despite the efforts made by the civilians, the Afghanistan policy and that of appeasing the ‘good’ Taliban is firmly in the hands of the military and Pakistanis will continue to pay a heavy price.

The hallmark of year 2012 was the speech made by Gen Kayani on August 14, in which he identified extremism and internal enemy as the real security threat. Sadly, in the four months that followed, we saw little or no tangible action towards the realisation of this policy shift within the military. This is why 2013 will be no different with lots of proxies and non-state actors doing their numbers. But the key difference is that Pakistan’s political parties and civilian institutions have come a long way in asserting themselves step by step. The completion of the current legislatures is but a small testament to the shifting nature of Pakistani politics.

Raza Rumi is Director Jinnah Institute and consulting editor The Friday Times. His writings are archived at www.razarumi.com.

Published in The Express Tribune, January 1st, 2013.