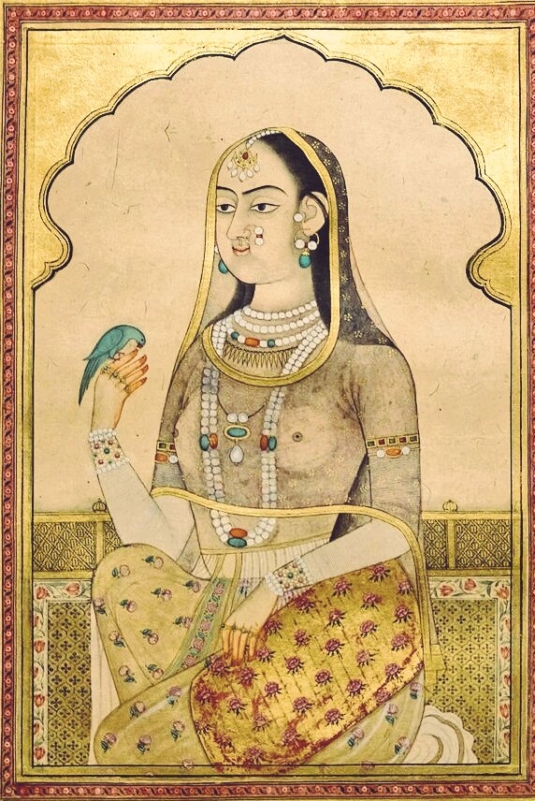

Mughal history ignores women of the empire, including Emperor Aurangzeb’s daughter Zeb-un-Nissa: patron of the arts, poet, and a keeper of several lovers – according to rumours. The eldest daughter, she was Aurangzeb’s close companion for several years. She was born in 1638 to Dilras Bano of the Persian Safavid dynasty. Loved by Aurangzeb, she was named carefully to reflect his station.

A favourite, she was exposed to the affairs of the Mughal court. With a sound education in the arts, languages, astronomy and sciences of the day, Zeb-un-Nissa turned into an aware and sensitive princess. She never married and kept herself occupied by poetry and a spiritual Sufi quest.

This is the irony – Aurangzeb’s daughter was an antithesis of her father’s persona and politics. Zeb-un-Nissa was both a Sufi and a gifted poet. The Divan-i-Makhfi – a major divan – is credited to her name. Given her father’s dislike for poetry, she could only be makhfi – the invisible.

There was subversion too – like all rebels she attended and participated in the literary and cultural events of her age, dressed in her veil.

Unlike her puritanical father, Zeb-un-Nissa did not share her father’s orthodox views on religion and society. Steeped in mystic thought, her ghazals sang of love, freedom and inner experience:

“Though I am Laila of Persian romance

my heart loves like ferocious Majnun

I want to go to the desert

but modesty is chains on my feet

A nightingale came to the flower garden

because she was my pupil

I am an expert in things of love

Even the moth is my disciple!”

(translated by Willis Barnstone)

Her verses, comprising 400 ghazals, and

published as Divan-i-Makhfi would have

bothered Aurangzeb.

Her inclusive poetic vision, comprising

the 400 ghazals in the Divan-i-Makhfi, ran

against the puritanical state and society that

Aurangzeb cherished.

“I bow before the image of my Love,

No Muslim I

But an idolater

I bow before the image of my Love

And worship her

No Brahman I

My sacred thread

I cast away, for round my neck I wear

Her plaited hair instead

(Divan-e-Makhfi)

In her poetry, Makhfi – the hidden or invisible

one – is a metaphor for her invisibility at the main Court and at the cosmic level the invisibility of God.

One of her long time companions was the émigré Iranian poet Ashraf. It is said that theirs was more than friendship and a literary association, and that there were hints of indiscreet liaisons. However, no direct evidence on this subject exists.

Zeb-un-Nissa is also said to have been excessively fond of one particular kaneez

(serving girl), Mian Bai. This intimacy was a subject of gossip. Perhaps it was the same Mian Bai who was gifted the Chauburji garden in Lahore.

The Chauburji building has the Ayat-ul-Kursi inscribed on the main gate. The date of its completion was recorded as 1646 AD by SM Latif, the famous Lahore historian who translated the Persian verse carved at the monument entrance:

This garden, in the pattern of Paradise,

has been founded

The garden has been bestowed on Mian Bai

By the beauty of Zebinda Begam, the lady of the age

According to Latif, Mian Bai was the favourite female attendant of Zeb-un-Nissa. Shah Jahan Nama also throws some light on the gardens and their gift to the lucky Bai.

Since Mian Bai had supervised the laying out of these gardens, the local people called it Mian Bai’s gardens. Respecting local opinion, Zeb-un-Nissa bequeathed these gardens to her favourite slave girl.

Eventually, she fell out of royal favour, not for her eclectic pursuits but for the rebellion of her brother Akbar, who proclaimed himself as emperor in 1681. While the rebellion was short and unsuccessful, Zebun-Nissa kept corresponding with her exiled brother; this landed her imprisonment in a Delhi fortress until her death in 1702.

A recent book, Captive Princess: Zeb-un- Nissa, daughter of Emperor Aurangzeb, attempts to examine the causes of her imprisonment, her worldview and reconstructs her life. The work highlights the political differences that she developed with her father and shows how alien Aurangzeb’s style of governance was to her soul. She never accompanied him on his Deccan campaigns.

Jadu Nath Sarkar states that Zeb-un-Nissa died in Delhi and was buried in the ‘Garden of Thirty Thousand Trees’ outside the Kabuli gate. It is said that when the railway line was laid at Delhi, her tomb was demolished, and the coffin and the inscribed tombstone were shifted to Akbar’s mausoleum at Sikandara Agra. According to SM Latif, a poet versified her chronogram in the following words:

A fountain of learning, virtue, beauty and

elegance

She was hidden as Joseph was in the well

I asked reason the year of her death

The invisible voice exclaimed: ‘the moon

became concealed’

Latif writes that the last phrase mahmakhfi-shud cannot be adequately translated. Literally it means the concealed moon, but makhfi was also the nom de plume of Zeb-un-Nissa and there is a meaningful wordplay here. However, much as we make conjectures about a full life lived, a good measure of the passions and poetry of the princess shall remain concealed and quite un-translatable.

First published by The Friday Times

Read many comments on this article from my older blog-site >>