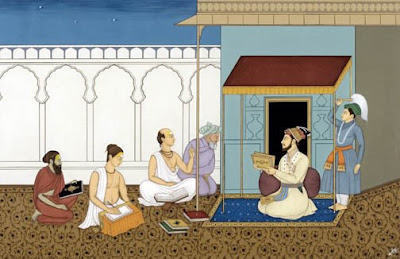

Prince Dara Shukoh, the eldest son of Emperor Shah Jahan, was like his great ancestor Akbar, a very liberal and enlightened Musalman and a true seeker of truth. Akbar respected all religions – Islam, Hinduism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Jainism, Sikhism, etc., and gave their votaries complete religious freedom. He was ever keen to discuss and understand their religious beliefs, practices and philosophy and, in order to make the Musalmans familiar with the culture, and universal values, philosophy and traditions of India, he had the great epics of India – Ramayana and Mahabharat – translated into Persian. He also arranged for the translation of the Atharvaveda.

Continuing the unfinished work of Emperor Akbar, Prince Dara Shukoh too, assisted by the Indian scholars, translated Bhagvad Gita, Prabodha Chandrodaya (a philosophical drama written in 1060 A.D.), and Yoga Vashishtha into Persian. He also translated the Upanishadas, which are the fountain-head of Indian philosophy, with the help of learned Pandits from Banaras, well versed in the Vedas and the Upanishadas. The translation of the Upanishadas by him entitled Sirr-i-Akbar (The Grand Secret) was completed on the 28th June 1657, shortly before the commencement of the War of Succession, which he lost to his crafty and unscrupulous brother, Aurangzeb who ruled India from 1659-1707.

Continuing the unfinished work of Emperor Akbar, Prince Dara Shukoh too, assisted by the Indian scholars, translated Bhagvad Gita, Prabodha Chandrodaya (a philosophical drama written in 1060 A.D.), and Yoga Vashishtha into Persian. He also translated the Upanishadas, which are the fountain-head of Indian philosophy, with the help of learned Pandits from Banaras, well versed in the Vedas and the Upanishadas. The translation of the Upanishadas by him entitled Sirr-i-Akbar (The Grand Secret) was completed on the 28th June 1657, shortly before the commencement of the War of Succession, which he lost to his crafty and unscrupulous brother, Aurangzeb who ruled India from 1659-1707.

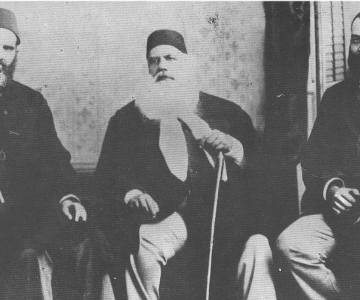

In the painting, Dara is shown translating the Upanishadas, assisted by Indian scholars.

Exhibit No. 3: Scene of Captive Dara being paraded in Delhi. (29th April 1659)

Exhibit No. 3: Scene of Captive Dara being paraded in Delhi. (29th April 1659)The painting based on Dr. Bernier’s eyewitness account, shows captive Dara Shukoh and his son being carried on an elephant on the streets of Delhi, girt round by troops ready to foil any attempt to rescue the prisoner, and led by Bahadur Shah on an elephant. Behind Prince Dara Shukoh is Nazar Beg, their goaler. Dara is shown throwing his wrapper to a beggar who had cried out, “Dara! When you were master, you always gave me alms, today I know well thou hast naught to give”. Describing the scene Bernier writes, “The crowd assembled was immense; and everywhere I observed the people weeping and lamenting the fate of Dara in the most touching language … men, women and children were wailing as if some mighty calamity had happened to themselves”.The outburst of popular sympathy for Dara Shukoh and the contemptuous response which Aurangzeb had received from the people for his outrageous treatment of his brother made him procure in all haste a decree from the Clerics in his own pay, and had his elder brother beheaded on the charge of apostasy.This was a sad end of a genuine seeker of truth, translator of the Upanishadas, author of many works on Sufi philosophy, and one who could have revived and carried the enlightened policies of his great ancestor Akbar to fulfillment.

Exhibit No. 4: Dara Shukoh’s farcical trial and verdict.

Exhibit No. 4: Dara Shukoh’s farcical trial and verdict.Dara’s immense popularity and sympathy for him among the masses was evident when he along with his young son was taken out on the streets of Delhi on the 29th August 1659 in a degrading manner (Exhibit No.3). The outburst of popular sympathy for Dara Shukoh and the contemptuous and sullen response which Aurangzeb had received from the people for his outrageous behaviour with his elder brother filled his dark heart with misgivings if Dara remained alive even as prisoner in the Gwalior fort or elsewhere. It was felt among his inner circle of confidants that Dara must be put to death without delay on the ground of apostasy.Following a farcical trial in absentia, the Ulama in pay of Aurangzeb decreed death for Dara for his infidelity and deviation from Islamic orthodoxy, and because “the pillars of the Canonical Law and Faith apprehended many kinds of disturbances from his life”. This was in reality a fraud on truth.Prince Dara Shukoh was killed and his severed head was sent to Aurangzeb to satisfy him that his rival is really dead. By his orders, the headless corpse of his brother was placed on an elephant and paraded through the streets of Delhi a second time and then buried without the customary washing and dressing of the body. The sketch portrays the trial of Dara in absentia and his severed head being brought before Aurangzeb.