By Najam Sethi

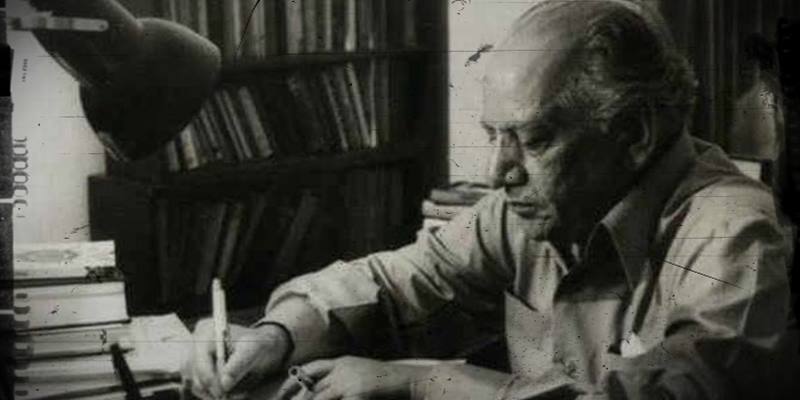

This year, South Asia celebrates the centenary of Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Pakistan’s pre-eminent Urdu poet in the classical tradition of the subcontinent. Faiz was the last of the five greats – Mir Anis, Mir Taqi Mir, Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, Allama Muhammad Iqbal and Faiz.

This year, South Asia celebrates the centenary of Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Pakistan’s pre-eminent Urdu poet in the classical tradition of the subcontinent. Faiz was the last of the five greats – Mir Anis, Mir Taqi Mir, Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, Allama Muhammad Iqbal and Faiz.

Writing one hundred years before Faiz, Mirza Ghalib would have recognised the former’s classical style and would have loved the new metaphor and colloquial touch of introducing common speech into the ghazal. One can imagine the great Delhi poet, who witnessed the demise of the last Mughal court and the destruction of the city’s Indo-Persian ethos, marvelling at Faiz’s metaphors – Dard aye ga dabbay paon liye surkh chiragh (and pain will come tiptoe, carrying its crimson lamp).

Faiz, a native of Sialkot, was taught Urdu and Arabic by Shams-ul-Ulema Syed Mir Hassan. Hassan had also taught Muhammad Iqbal. At Government College in Lahore, where he did an MA in English literature, Faiz was taught by A S Bokhari, also known as Patras. For part of his life, Faiz was associated with the Communist Party of Pakistan, and even when he disagreed, he remained a lifelong Marxist. His poetry was informed by his politics and he frequently voiced the aspirations of the common man, the down trodden and exploited. When he first rejected autocracy and dictatorship, and suffered imprisonment as a result, many marginalised him politically as a ‘poet of the Left’. Today, his ideological adversaries find solace in his verse.

Faiz’s first collection of poems, ‘Naqsh-e-Faryadi’ came out in 1941 when he was teaching at Hailey College in Lahore. He edited the progressive literary journal Adab-e-Latif till 1942, when he joined the British Indian Army for a few years and resigned as Lt Colonel. In February 1947, he joined Progressive Papers Ltd in Lahore as chief editor of The Pakistan Times and Imroze , under the inspiring leadership of Mian Iftikharuddin, whilst also taking part in labour politics. In 1951, Faiz was arrested along with communist leaders for conspiring to overthrow the government of Liaqat Ali Khan. He was in jail until 1955 and wrote some of his best poems in this period. He was also arrested and jailed in 1958 under the first martial law.

By then, Pakistan was firmly on the side of the United States of America in the Cold War. Its negative foreign policy yardstick was India, and it seemed to sacrifice all political values in pursuit of this revisionist obsession. The first casualty was democracy itself, barely a decade after Pakistan’s establishment. The military dictated foreign policy and twisted domestic politics to support it. Elections were not considered necessary under military rule until rigging became the norm and fair elections became the alarm bell of instability. The world, and voices of reason within like Faiz, could not persuade Pakistan to change tack and become normal, not even after the loss of East Pakistan in 1971, trashing the aphorism that nations learn from defeat.

Going with the US in the Cold War meant nourishing the germs of religious extremism that the founders of Pakistan had sought to sanitise. Since the opportunism of US policy dictated support to the clergy in the Islamic world, it legitimised the assertion of religious identities in Pakistan which was later to cause the virus of sectarianism domestically and isolation abroad. The Pakistan military, unmindful of the lessons it should have learnt, fell into the trap of US-inspired covert war in Afghanistan, spear-headed by jihadists that it also used in cross-border terrorism in Kashmir.

All this has finally brought Pakistan on collision course with a more pragmatic America in this post-Cold War age. Despite the consensus amongst all of Pakistan’s vote garnering political parties, its business people, economists, and students of political science, Pakistan’s military is unable to change its India-centric direction. The resulting global isolation and gradual implosion because of internal discord and terrorism inflicted by Al-Qaeda and the state’s jihadist proxies, have all brought Pakistan to its knees. Ironically, as the Middle East rises against its tyrants in favour of a representative system, the coming state-inspired ‘revolution’ (anarchy) in Pakistan will be in the opposite direction, against its representative system.

Fittingly, Faiz’s centenary is being celebrated symbolically in Pakistan and India by those who want peace in the region. If you ask ordinary people who is the great living poet in Pakistan today, most people will be at a loss. But the truth is that Faiz still strides like a colossus over every word or deed that is rational, sincere and authentic in our short and tragic history. When finally the lands and peoples that compose Pakistan emerge from the dark ages that are upon us today, it is men like Faiz who will be the champions, their voice giving words to the anthems of a free people. When finally peace with our neighbours becomes an economic and social necessity, it is men like Faiz with their sympathetic vision who will be the bridge between erstwhile antagonists. And when finally Pakistan learns to live like a responsible state in the world, it is the universality of voices such as Faiz’s that will redeem us and be our link with other civilised societies.

Published in The Friday Times