After 30 years of self-defeating policies, the new National Internal Security Policy may be the right way to make a fresh start

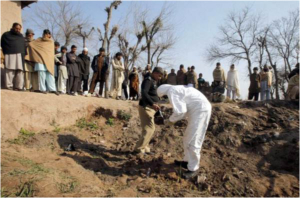

Pakistanis should be grateful for small mercies. The federal cabinet finally approved the draft of the internal security policy that was pending for review since December 2013. This is some improvement from the earlier performance of civilian authorities and complete outsourcing of security question to the military. The approval does not suggest that the military has backed off and the civilians are fully in charge. In fact, reports suggest that the military leadership has proactively argued for a cleanup in North Waziristan Agency (NWA) and had advised the Prime Minister for not delaying the final putsch any further.

The National Internal Security Policy (NISP) has a detailed conceptual part that highlights the extent of damage that Pakistan has suffered during the last 12 years. While reporting on the victims of terror, the NISP notes that from 2001 to November 2013, 48,994 people were killed in the country including 5,272 personnel of the law-enforcement agencies. The attacks on security apparatus accelerated during 2011-2013 as 17,642 casualties including 2,114 security personnel took place during this time period. The NISP notes that with more than 600,000 strong personnel in 33 civilian and military security organizations provide adequate capacity to the Pakistani state to fight terrorism. The impact of terrorism has been calculated as losses worth $78 billion to Pakistan’s economy. Surprisingly, the draft also refers to the foreign policy priorities with respect to Afghanistan, Kashmir and India and limited civilian input in policy process. Governance failures also find a mention in the draft.

The democratic process in Pakistan has been a victim of terrorist narratives

Perhaps the most important feature of the NISP refers to the emphasis on the narratives – political and martial – which have increased the domestic support for terrorist outfits and mislead many a citizen in believing that terror tactics are justifiable at a certain level. This area has been largely unaddressed by Pakistan’s political parties and permanent state organs. While the PPP-led coalition tried to make some amends, it was often cowed down into acquiescence by militancy all around. In fact, the elections of 2013 took place under the threat of Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) that decided which political groups had more space to campaign and contest. Certainly, the democratic process in Pakistan has also been a victim of terrorist narratives.

Fulfilling the legislative mandates of NACTA seems to be the key focus on the implementation of NISP. The strengthened and revamped NACTA would include a ‘directorate of internal security’ to collect and analyse intelligence from six intelligence agencies, including the special branch operating at the provincial level, and coordinate efforts of 20 or so law-enforcement agencies (LEAs). The draft document had estimated Rs 32 billion as the cost of implementing the policy. Let’s hope that the federal and provincial governments would agree to fully resourcing NACTA instead of making it another victim of government budgetary delays.

At a strategic level, three approaches – Dialogue, Isolation and Deterrence – define the framework of NISP. The NISP would need a more detailed implementation framework especially at the provincial level to operationalize some of these approaches. It is encouraging to note that the state might, other things being equal, move ahead with ‘fixing’ the national narrative on counterterrorism and extremism and reset the decade old spin that terrorism is a reaction to US presence in Afghanistan. Similarly, the de-radicalisation and reintegration strategies would need stocktaking of the Islamo-nationalist construction of Pakistani state and reversing some of the poison that school curricula have spread in the younger people. The youth engagement strategy also finds a place in the NISP and this is where the political parties would need to forge a consensus beyond their narrow interests and electoral triumphs.

Most importantly, the NISP would need well-calibrated provincial documents with exclusive focus on LEAs, education and development. Most importantly the criminal justice system is a provincial domain and without improving it and investing in prosecution and investigation capacities of the police, the NISP objectives would not be fully achieved.

The NISP cannot decide the foreign policy but its objectives must inform the goals of our engagement with neigbhours. Iran, India and Afghanistan have a list of complaints against our conduct and priorities. Nawaz Sharif has time and again expressed his resolve to correct the historical mistakes but he cannot do it alone. He would need to work closely with the military and inform their doctrines. The only way he can do it if he has the backing of political parties and public opinion. Therefore, it would be in the interest of the PMLN to pursue the national campaign on counterterrorism and extremism. In the process, it may have to abandon some of its allies in the Punjab and also deal with the backlash of the militant groups. This is not an insurmountable challenge if only the political class would look beyond its short-term horizon.

If the state repeats the mistake of pushing jihad in Syria, then we are not restructuring the jihad industry

A strategic area that for obvious reasons could not be highlighted in NISP is large space for breeding extremist views within the state institutions. Sectarian loyalties, Islamo-nationalist dreams and xenophobic worldviews are common to the way a mind is shaped within Police, civil servants and even the military. These institutions will have to deal with demons inside. Some headway has been made by a crackdown on Hizb-ut-Tahreer inroads within the army but the overuse of religious identity will have to give way to the idea of a prosperous, modern nation-state. Otherwise no form or shape of a contemporary Islamic state can meet the expectations of an imagined Caliphate which is a cynical ploy of Islamists to capture political power.

Given how Pakistan functions, it is not surprising that the NISP approval comes after a military operation commenced in NWA. The indications that the military is having a rethink about the Haqqani network and other sections of Afghan Taliban who support TTP is a welcome signal. At the same time, Pakistan’s inclination to espouse a Saudi worldview on Syria is most worrying. If the state repeats the mistake of pushing jihad in Syria then we are not restructuring the jihad industry. Pakistan’s long term security and economic progress requires that it dismantles and reintegrates the jihad outfits and stop viewing them as instruments of ‘state power’. We can only hope that the civil-military elites have learnt a lesson or two from the thirty years of disastrous, self-defeating policies.

This is why the NISP may be the right way to make a fresh start.