Listen to the story:

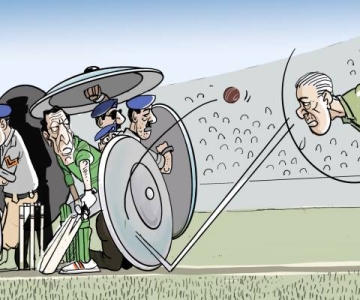

Steve Inskeep talks to Raza Rumi, editor of the Pakistani newspaper Friday Times, about the rise in attacks against journalists. Rumi fled Pakistan after surviving an assassination attempt last month.

TRANSCRIPT:

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

A man came by our studios this week who cannot go home. He is known by the name Raza Rumi. He’s a writer and television host in Pakistan – or at least he was until gunmen opened fire on his car. And now he’s staying outside …

RAZA RUMI: I’m taking a break from the very toxic and very violent environment that I was reporting on, writing about, speaking about. I finally became a victim of that. And not just me but my driver, who was with us, was shot dead. You know, and he died in front of me. So, it has been extremely traumatic.

INSKEEP: Raza Rumi ducked when the bullet struck his car. His driver did not. Dozens of journalists have been killed in Pakistan in recent years. Just last weekend, another TV anchor was shot and wounded. Raza Rumi told us what it’s like to speak out in an insecure country. In newspaper columns and on television, he criticized extremists such as Pakistan’s Taliban. On his final TV program, he raised questions about Pakistan’s blasphemy law. That law is used to target Christians and others accused of insulting Islam. In the days before the attack, Raza Rumi says, callers to his show gave him a label that can be a death sentence. They called him a secularist. Were they right?

RUMI: Yes. There were many callers like that who would say that, you know, you are secular, which unfortunately I do not blame them. Because what has happened is that in the decades of Pakistan’s existence, the Islamic scholars and the villages’ parties particularly have inteprated the word secular as an atheist or as irreligious or somebody who’s anti-religion. And so that’s the popular perception. Secularism is an abused word. I mean, I’ve actually stopped using it on my TV shows. You know, I would use things like moderation, pluralism, you know, only to appease these bullies. And, you know, now thank God I can say that, you know, I’m a committed secularist. I think that is the only way states ought to be, societies can only function normally if they are secular. Because if they started to become partisan or particularistic, then obviously you have violence and divisions and discord and hatred. And I think that’s just not on because, I mean, here I am a victim of all of that.

INSKEEP: Twenty bullets struck the car, was that correct?

RUMI: Well, yes. The police found 11 shells from the car. But, you know, there were more bullets. And, you know, I don’t have access to the exact investigation report, but, you know, it was over 20 bullets because some were sprayed in the air to first make sure that all passersby ran away, nobody gathered around the car because there was an operation going on.

INSKEEP: Very courteous of them to warn away civilians before they attempted to kill you.

RUMI: Yes, small mercies.

INSKEEP: How dangerous is it to be a journalist in Pakistan right now?

RUMI: It is extremely dangerous if you cross certain lines in Pakistani journalism. And those lines are when you get into direct confrontation with the state authorities or you get into a confrontation with the non-state actors. And non-state actors include both the extremist armed groups but also some sections of gangs affiliated with political parties. But it is extremely dangerous. If you don’t cross those lines, for example, if you ever talk about Christians and (unintelligible) and Shias and bigotry, etc., you’re safe. If you say the Taliban are great. If you feel the fight of al-Qaida against the West is kosher game, you’re safe. But if you cross these lines, you are unsafe.

INSKEEP: As you’re talking, I’m remembering a woman I knew in Pakistan named Perween Rahman. She was not precisely a journalist – she was an activist and a writer – but she revealed facts, she uncovered facts. And once she said to me, roughly speaking, please write what I’m writing so that I’m not the only one writing it. And I think about the fact that not long after that conversation, a few years after that conversation, she was killed. It must be a very lonely moment when you’re a writer and you’ve written something that you know could get you killed and you’re about to hit send – send it out to the world.

RUMI: Yeah. Yes, it’s a lonely moment but it is also cathartic. It is also cathartic because how could you be a conscientious, patriotic citizen of your country and not speak against injustice, not speak against, you know, the daily violation of rights of your fellow citizens. And I love my country, you know. I really think Pakistan has immense potential, you know. Wherever Pakistanis go, they make a mark. But what happens within Pakistan that you know such incidents occur. And I think those are the things I was trying to unpack.

INSKEEP: Can you ever go back?

RUMI: Steve, I would love to go back. That is what I want to do but I don’t think I can immediately go back. But I can perhaps go back and have a hermit’s life in my home, but I would have to go out somewhere and somebody would go with me. And I don’t want another person to be killed because he or she was with me. A 25-year-old guy, head of a household, young, promising, who had his whole life ahead of him died in this confrontation between the extremists and the looney liberal voice. And I can’t kind of forget that, at least for now.

INSKEEP: Raza Rumi is a Pakistani journalist who for the moment is staying in Washington.

Original Post NPR