Democracy is like an infertile woman that cannot produce anything, thundered a popular columnist (a real opinion-maker) at the Association of Physicians of Pakistani Descent in North America (APPNA) convention held in Washington, DC. A few women participants objected, but overall, the trashing of democracy back home in Pakistan was applauded by many a successful professionals present in the audience. Later, at another event I heard the view by a speaker that Muslims and democracy are incompatible. These are not isolated sentences. A worldview that Pakistan’s Urdu media has cultivated considers democracy a colonial legacy that the British left. A few go to the extent of arguing that in an Islamic Republic a Caliphate is the only option.

Another columnist recently wrote how our democratic and constitutional system is the rotten dress which protects certain segments of society and now the time had come to decide if we could live with an itchy body [politic]. Considering that half of Pakistan’s existence has been under the rule of a narrow group of civil-military bureaucracy, it is difficult to argue how can even a most imperfect democracy not be more inclusive?

Senior journalist Nusrat Javeed only recently bitterly complained about how some of his colleagues on television were inviting martial law and that made him ashamed of being a journalist. My favourite columnist, Mr Ayaz Amir, whose writings have inspired us all, has been cynically reviewing the current crisis as the sound of marching boots. That may well be as our history tells us. But references to 111 Brigade (which takes over Islamabad during a coup d etat) and democracy’s swansong reflect as well as engender fatigue and impatience with the constitutional order.

In the brewing crisis within Pakistan’s power circles where Punjab-based parties are pitted against one another with overtones of a civil-military collision, the media has emerged as a player. In 2007, a newly independent media had a pro-democracy, pro-justice stance. In 2014, a tamed version of its older self is propelling a doomsday scenario and seems to have lost direction. Analysts have pointed out how the current revolution would be severely punctured if the television cameras were switched off for some time.

Sensing the power of media (its role in ousting Musharraf as well as discrediting the previous PPP-led coalition government), the power centres elected and unelected have been eager to tame it. The recent media crisis has left the Fourth Estate disunited, and at the mercy of what is colloquially referred to as a polarised anchoracracy. Thousands of media workers editors, reporters, cameramen, correspondents, etc pale into in significance in comparison with a few elite prime-time oracles. And that is where the state and political parties enter the fray. Imran Khan was the hot favourite of a certain media organisation until the last elections. But now he has publicly disowned the media group at the sit-ins. Thus, a strange tamasha is going on as Pakistan’s fragile democracy unravels under the unbearable burden of heavyweight politicians.

Nearly 50 channels have been televising the protests of Imran Khan and Tahirul Qadri live; and have created an atmosphere that a change is imminent. This has another effect the shrinking space for dialogue, compromise and negotiation. Hardline speeches by leaders are followed by a commentary that is polarised, highly speculative offering a free-for-all ground where democracy and its ills are recounted by the hour. This engenders further political instability and influences the susceptible minds. No wonder many PTI/PAT supporters on social media state that a martial law is acceptable if the prime minister does not resign within the deadline (also a flexible notion in this mayhem) set by their leaders. Preparing the narrative for a military takeover is a disservice to Pakistan including the military itself, which is waging a major operation in the northwest of the country.

How is news coverage determined then? A million internally displaced people and their everyday miseries would have been news in ordinary circumstances. A host of other issues that need to be informed via news bulletins and commentaries have taken a complete back seat. This gives a dangerous impression of the media being a stakeholder or worse, a party to this crisis?

Two TV channels were taken off air for select periods in the past few months. One faces the wrath of cable operators and blasphemy law has also been invoked in the intra-media struggles. Can the industry be a guardian of public interest in such a climate? Needless to say, the regulatory structures, including the regulator PEMRA, have been royal failures in the process.

More importantly, the media owners and editors have not come up with a clear and enforceable code of conduct, a non-negotiable list of professional standards of professionalism and journalistic ethics that may guide workers from celebrity anchors to field reporters. Never has the need for an independent regulator been so critical. Those who cite the infancy argument should end the empty excuses. Twelve years later, the beast is no longer an infant.

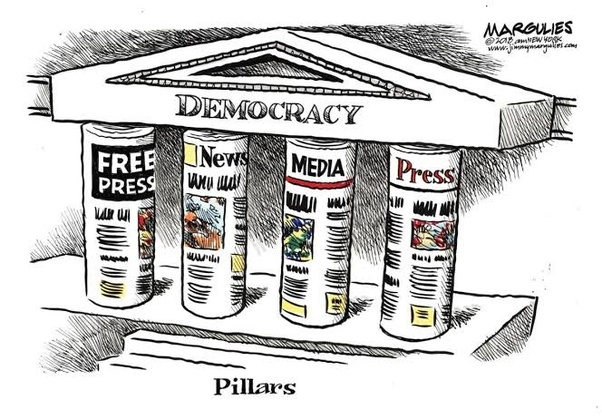

The Augean stables within media houses need a massive clean-up. Only they can do it and it is time they started. Public accusations of real or perceived partisanship and ill-advised power play will only further damage the already dented credibility of the industry. Lastly, a free media only operates in a democracy. In other revolutionary models of governance, media freedoms shall be the first casualty.