When empire strikes back, but the Force remains strong in the arts and academia of contemporary Muslim countries. I spared with Sadia Abbas

As the world moves into a maddening phase of Islam versus the West, Pakistani academic Sadia Abbas presents a layered narrative in her book, At Freedom’s Limit: Islam and the Postcolonial Predicament (Fordham University Press, New York), on the contours of a new, imagined view of Islam. In great detail and with crafted nuance, she analyses the complexities of the postcolonial condition of Muslim societies and Muslims, and the myriad modes and facets of anticolonial ambitions.

Abbas’s study is unique because it delves into the intricate relationships between Islam, empire and culture, and weaves the story of the current crises that inform the lives of Muslims and their societies, through a literary lens. This study, in effect, presents an alternative discourse to the debates that surround depictions of both Islamic terror and Islamophobia. At Freedom’s Limit suggests that the complex histories of identity and struggle at the global level are vital to understanding the new Islam that has emerged since the early 1990s.

The postcolonial state’s management of icons is crucial to the state’s policing of the boundaries of Islam

This new representation of Islam started to take shape in the late 1980s when Salman Rushdie’s book, The Satanic Verses, invoked violent passions among some Muslims and thereby delineated a marker between the civilised and the violent. This was also when the Berlin Wall was demolished (1989) and the first Iraq war (1991) was waged to liberate Kuwait. However, these brewing forms found a new shape and discourse after the events of 11 September 2001 when this imaginary notion of Islam found a whole new meaning and changed the world.

According to Abbas, the key elements of this new conception of Islam comprise debates around the veiled or pious Muslim woman, the militant and the Muslim injured by free speech in the West. A central argument she presents is that freedom, as used in mainstream parlance and particularly in popular culture is one that is imagined as modern and Western, thereby reverting to a peculiar imposition of Enlightenment. Abbas unpacks a plethora of such Eurocentric terms and critiques their application as expressions of imperial discourse creation. For instance, the pious Muslim outraged at the West and injured by its values may, in effect, be wishing for enslavement and is, therefore, envisioned as freedom’s other?

Taking this critique of the contemporary view of Islam in anthropological terms, Abbas undertakes a sweeping overview of cultural production, employing references from television, cinema and novels. Interestingly, the book ends up showing how the most nuanced contestations of Islam today are contained in the works of Muslim intellectuals and artists.

At Freedom’s Limit gives a critical and, at times, scathing account of contemporary cultural discourses that encourage amnesia with respect to the imperial and colonial history of many Western countries. Abbas’s outstanding reading, for example, of the [ill] famed film Zero Dark Thirty (which depicts the hunt for Osama Bin Laden by US government officials) dwells on this theme and also comments on the history and present forms of torture used as policy instruments.

In a chapter titled The Echo Chamber of Freedom: The Muslim Woman and the Pretext of Agency, Abbas opens up the question of the repressed Muslim woman (of whom we have heard so much in the wake of the Iraq and Afghan wars). Using sharp analytical arguments and a good dose of wit, the author presents a formidable critique of the work of Saba Mahmood, a prominent thinker and academic. Mahmood’s celebrated ethnography of the women’s mosque movement in Egypt, Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject, explores the alienation experienced by secular men and women across the Middle East in the context of the Islamist- and US-dominated politics of the 1970s and 1980s. Rather than political activism, the women active in the mosque movement of Egypt relied on practices that concerned personal piety, which seem closer to an adoption of the clergy-set patriarchal version of Islam. Mahmood shows how this reaction was, in effect, a response to Egypt’s imposed secularist and Westernised values. Abbas demolishes, bit by bit, this narrative around conservative Islamic practices and hints at the dangers of Mahmood’s position.

In a chapter titled The Echo Chamber of Freedom: The Muslim Woman and the Pretext of Agency, Abbas opens up the question of the repressed Muslim woman (of whom we have heard so much in the wake of the Iraq and Afghan wars). Using sharp analytical arguments and a good dose of wit, the author presents a formidable critique of the work of Saba Mahmood, a prominent thinker and academic. Mahmood’s celebrated ethnography of the women’s mosque movement in Egypt, Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject, explores the alienation experienced by secular men and women across the Middle East in the context of the Islamist- and US-dominated politics of the 1970s and 1980s. Rather than political activism, the women active in the mosque movement of Egypt relied on practices that concerned personal piety, which seem closer to an adoption of the clergy-set patriarchal version of Islam. Mahmood shows how this reaction was, in effect, a response to Egypt’s imposed secularist and Westernised values. Abbas demolishes, bit by bit, this narrative around conservative Islamic practices and hints at the dangers of Mahmood’s position.

In building her argument through the six chapters of the book, Abbas brings to the reader a rich analysis of contemporary cultural references and adds to the theoretical frameworks that have emerged around issues of modernity, agency and freedom. The references discussed include Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker, British TV spy series Spooks, Orhan Pamuk’s Snow, Leila Aboulela’s The Translator and Minaret, Mohammed Hanif’s A Case of Exploding Mangoes, Nadeem Aslam’s Maps for Lost Lovers and The Wasted Vigil, among others. Her painstaking research entails commentaries on Islamist literature, colonial texts and postcolonial legal frameworks. In fact, the book is seminal in presenting a comprehensive critique of major works of contemporary Pakistani fiction in English. Abbas weaves the value and significance of these literary voices from a postcolonial Islamic country and its diaspora in her discussion of new Islam.

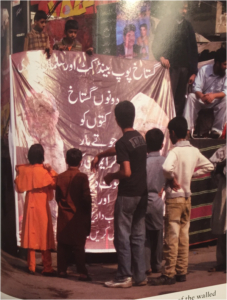

A substantial part of the book explores the idea of Muslim religious injury and the contested debates that deal with representations of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). Abbas traces the connection to not-too-dissimilar controversies related to religious icons, commonplace during the European Reformation and Counter-Reformation. These are the most fascinating parts of the book. While looking at the blasphemy laws in Pakistan an instrument inserted by the British colonial administration in India Abbas builds a detailed discussion of the genesis of the idea as well as how various communities have responded to and interacted with the law.

In Pakistan, holds Abbas, the postcolonial state’s management of icons, and of attachment to the Prophet (PBUH) turns out to be crucial to the state’s policing of the boundaries of Islam and in the process securing its own conceptual borders. This is an extremely pertinent observation as the trajectory of the blasphemy law acquired a new dimension following the official emphasis on the ideological frontiers of the state under General Zia-ul-Haq.

The book’s last few chapters probe deeper into the works of Hanif and Aslam and the artistic output of Komail Aijzauddin and his use of Christic iconologies from Byzantine, Renaissance and Baroque painting to reflect on the status of religious minorities in Pakistan. Aijazuddin’s work, according to Abbas, makes meaning by employing iconography that is paque and inimical to the state.

Abbas has created the umbrella term Cold War baroque as a device to posit the contemporary dynamics of new Islam and its interaction with the West. She defines this as a set of the aesthetic imagination of icons and iconographies poised against the cultivation of iconoclastic and anti-aesthetic branches of Islam by the US and Saudi governments and third-world nationalist and praetorian regimes. Such a theoretical perspective, aided by the works of Pakistanis at home and abroad, allows one to fathom the complex understandings of the intimacy between the Americans, the Pakistani secret service and jihadi groups. According to Abbas, this relationship has, over the past decade, been reconfigured as a war against terrorism.

At Freedom’s Limit is an important work that adds much-needed depth to debates on Islam, Islamophobia and the artistic representations coming out of Muslim countries such as Pakistan. The author’s arguments are both fresh for their insight and original for their ability to provide a sound framework for further research and inquiry. It is a book that needs to be read and taught within Pakistani academia.

(Below, TFT talks to Sadia Abbas about her academic work.)

RR: You have delved into the imperial debate in considerable detail. By attaching too much importance to imperial hubris, aren’t academics minimising the agency of Muslim elites and societies?

SA: I’m a scholar with a historical bent and I don’t think we can understand what’s happening globally without talking about the historical processes that have shaped Muslim-majority societies and Muslim elites and colonialism and imperialism are serious factors. I believe in double critique, so I don’t think one comes at the expense of the other. I don’t find the word agency of much use; I think responsibility (which I prefer) is important and there is plenty of that to go around. I dwell on the decisions made and rhetoric employed by local elites as well, so I’m not sure what that says, unless we shouldn’t speak of empire at all, which means we shouldn’t talk about history (or the present in any kind of complicated way). But people are welcome to think I’m attaching too much importance to the imperial aspect. I don’t think I am, but that’s for people to decide themselves.

RR: Is the Islam-versus-West debate redundant and an oversimplification?

SA: Yes, it is and it only feeds the most reactionary forces on all sides. For instance, it’s hard to imagine Europe historically without thinking of the constitutive influences of various Islamic civilizations in (say) Spain or Greece. Scholars are paying more and more attention to that. I’m hoping to work on some of that in one of my next books. Also, there were Muslims amongst African slaves in the US and I do think one has to reckon with the role of that presence in the formation of American civilization. There’s a tendency to not want to think about such issues (especially because of the racial component) in Pakistan, and Pakistanis and Indians here sometimes want to act as if they are white harder and harder to do since 2001 though it may be.

RR: The War on Terror has generated a new global discourse. How is it evolving and what direction[s] might it take?

SA: The War on Terror has oversimplified everything, drawn awful battle lines, all the while leading to global security regimes that are being used to protect the interests of neoliberalism at a moment when we need a serious critique of the economic condition of the world. Between brutal imperial and postcolonial security regimes, fanatical sectarianism and religious bullying, and growing disparities of wealth, it’s all quite bleak.

RR: There is a fascinating discussion of Pakistan’s literary and artistic trends in your book. Is that a response you think is local or more integrated with the global market? The fact that English writing by Pakistani authors is read more outside the country is a dilemma.

SA: I discuss Mohammed Hanif, Nadeem Aslam, Hanif Kureishi and Komail Aijazuddin, all of whom are engaged in complex and formally sophisticated performances of internal and double (of empire, racism and internal social forces) critique. Some are diasporic; others are not. The global marketplace is one factor among many shaping their reception and performance. But so are all sorts of global forces that have very local effects. Moreover, in a country that has labour working all over the world, I think we need to think carefully about the global as well as the local, and about the many meanings of diaspora. I respect what these writers and artists (and many more) are doing and am glad they are doing it. My own critical orientation is such that I’m much more interested in what they’re doing than in how they are being received (although the latter has its importance).

RR: And on being read outside the country?

SA: I’m not sure what to say about people reading them more outside the country. It seems people are reading them plenty within the borders as well. Having said that, literacy is a serious issue in all the languages and needs to be addressed. One of the things we need is more discussion of vernacular literature. I just met this poet, Irfan Malik, and I found myself asking to be taught Punjabi. I could follow some of the poems a friend of ours introduced me to, with help and instruction and who knows where that might lead. A couple of the poems he recited were just wonderful. Those of us who were English medium-ized need to learn more. We need to pay more national and international attention to Sindhi, Baluch and Pashto literature as well (although perhaps the writers would like to be left alone. I don’t know). Urdu gets a little bit more attention. I wish we were taught all the local languages in our schools. We spoke Urdu at home and my parents are very articulate, but it wasn’t emphasized in the schools I went to and I feel thoroughly undereducated. And my graduate research took me in a different direction.

RR: Your book has dwelt quite a bit on Komail Aijazuddin’s artworks as representative of Pakistan’s embattled secularists? Do you think that Pakistan as an avowedly Islamic republic will give space to such movements?

SA: I don’t call Aijazuddin representative (I don’t think truly fine artists ever are). I think of him as part of a very particular emergent formation, which I call Cold War Baroque. There’s amazing work being produced across Pakistan, but I was particularly interested in the way his work addresses the history I was interested in, and the way he uses seemingly outmoded techniques. He would routinely be critiqued when he was a student in the US because people didn’t understand what he was doing or why it mattered. I think a great deal of his work is actually very tender about the religious tradition, despite its secularism.

RR: The issue of the blasphemy laws, many argue, is located in the context of postcolonial society’s adjustment and metamorphosis. In Pakistan and elsewhere, how do you see that changing in the future?

SA: I have no idea. It’s a complicated historical moment and everything seems up for grabs