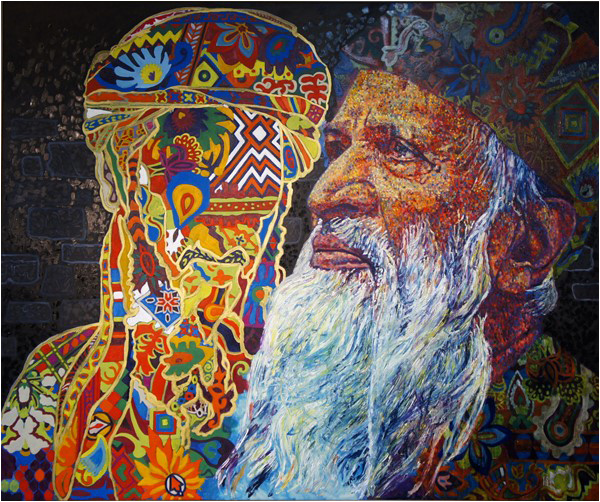

The man who defied a callous state and society, unbowed in his love of humanity

The death of Abdul Sattar Edhi after an extraordinarily productive and unreal life stirred emotion in every Pakistani. United in grief, the country mourned, rising above the racial, ethnic and other faultlines that divide Pakistan. Edhi’s humanitarianism defined the best and the worst of Pakistan and its fractured society. Six decades of Edhi’s tireless public service were familiar to everyone. The credibility of the Edhi Foundation as a place to contribute was matchless and perhaps no other institution inspires such confidence. Yet Edhi’s dedicated public role as an incredible individual and leader of a huge network was a reflection of the gap that the state had left in terms of meeting its basic functions of delivering dignity, reliable and affordable services and fulfilling its constitutional mandates.

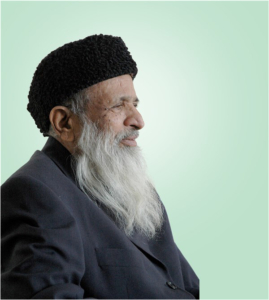

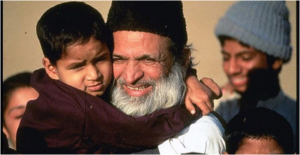

My earliest memory of the Edhi magic was a traffic jam on Lahore’s Mall Road. Like all impatient teenagers, it was annoying to get stuck in the traffic. Unlike other traffic nightmares, this was calmer and festive. Everyone knew that Edhi sahib was at Charing Cross, collecting donations. Hundreds had gathered around him, shaking his hand. Our driver Iqbal, who did not earn much, took out a ten-rupee note and stepped out to donate to the bearded man’s mission. Under different circumstances, Iqbal would be furious and aggressive on the road but there was something about the occasion that could temper his annoyance. This was not the first or the last time I saw the old man. But Edhi’s story is not about meeting him, hugging him or spending time with him. The saint-like figure was not given to small talk or formalism. He was direct, passionate, earthy and utterly driven till his last.

The groundbreaking nature of Edhi’s as a quiet revolution has yet to be fully appreciated

Later, as a young a civil servant I arrived in the field (as they say) to govern a sub district comprising the un-serviced rural areas or cruel small towns, and I realized the function that Edhi was providing. In small subdivisions where I was trained or posted for district management, an Edhi ambulance was virtually the lifeline. In small towns of the Punjab and the hilly areas of Murree and Kottli Sattian, the most reliable access of common citizens was Edhi ambulance service, or the shelters that were available. In times of floods and other disasters, the Edhi Foundation was ahead of everyone. This was the time when jihadists had not expanded into disaster relief services and the Edhi network was virtually the fastest and most dedicated of civic groups.

As the assistant or deputy commissioner you have little or no formal control over delivery of basic services such as health, education, water supply etc, but the provincial government expects you to manage, control and oversee. Through the decade of my work, I realised the sheer magnitude of state failures in getting the basics right. But I also discovered how nongovernmental networks such as Edhi foundation were alleviating the obvious abandonment of the poor, the marginalised and the vulnerable.

How long would the Pakistani state need Edhis to render tasks that it has miserably failed to perform?

Pakistan’s story of growth without development has been written about in detail. Billions of local and external resources are pumped into a broken system that does not yield results. Half of our children are out of school. A small fraction get basic health services and even a smaller fraction have access to tertiary care in hospitals. Before the Musharraf regime reorganised the emergency rescue services, an Edhi ambulance was the source of rescue and relief. It still beats the state service in many parts of the country. Worse, the state’s social care has remained abysmal. From orphanages to morgues, and from rural clinics to children’s facilities, state services spell negligence, corruption and in most cases plain absence. In this unimaginable morass, Edhi was a beacon, personifying an endless struggle to fill in a black hole.

Edhi was a rebel from the very start. He commenced the charity work within his Memon community and when he realised that most of the humanitarian work was confined to that particular community, he moved away and set up his own clinic. Overtime, the work expanded and consolidated and so did Edhi’s selfless reputation. His wonderful biographer Tehmina Durrani records in her book A Mirror to the Blind as to how Edhi picked up dead bodies from rivers, from inside wells, from road sides, accident sites and hospitals, when families forsook them, and authorities threw them away. He bathed them, gave a decent burial and never bothered about whom he was tending to. Such was the extent of state failure and the vision of unassuming Edhi that he step by step expanded his services. From taking care of abandoned dead bodies to setting up shelters for women, children, elderly and drug-addicts, Edhi continued with his multiple missions. Overtime the charitable work expanded beyond Pakistan as Edhi organised relief and aid during many emergency situations across the world.

By the time, Edhi died, his foundation was raising billions of rupees each year without government support, without the crutches of international development assistance that is often designed with much fanfare. More than 1800 ambulances worked 24—7 to reach those in need of help. Dozens of Edhi homes took care of thousands of children in a country where public sector facilities of such kind are absent.

The groundbreaking nature of Edhi’s as a quiet revolution has yet to be fully appreciated. Pakistan has no adoption law since adoption is not preferred by the tenets of Islamic jurisprudence, Edhi’s work opened up possibilities for many children to find homes. Children born out of wedlock and sometimes the unwanted girl child could face abandonment at a trash heap or plain murder. This is where Edhi’s challenge to the social norms was the most meaningful. Such children were not only rescued but also given a real life. The famed jhoola or cradle became a larger metaphor for a charity turning into something larger a life support system. In welfare-oriented societies, this role is assumed by the state.

Edhi disregarded the clerics who raised objections to adoption and the provision of full rights (such as inheritance) to the adopted. His subtle rejection of orthodoxy was essential to maintain the humanitarian scope of his work. The untiring man could do it because he had people’s support; he internalised the strength of those who recovered under his care and those who backed him. Above all, he believed in himself in the unpretentious manner, which is rare.

But Edhi’s work was also possible because millions of Pakistanis were willing to reach out. Pakistanis are philanthropic by nature. Partly inspired by the faith where annual charity is mandatory, there are strong non-Islamic cultural traditions at work. The best-known public institutions such as hospitals, schools among others, in Lahore and Karachi were built by generous patrons in the early part of twentieth century. In recent times, the annual giving is estimated to be more than Rs. 240 billion (or 2.4 billion dollars). And these are conservative estimates. Edhi got a little chunk of that but consistently; and this was central to an enduring relationship between concerned citizens and a private humanitarian foundation. The state remained indifferent, sometimes obstructionist, but it did not think of replicating this great model. Driven by authoritarian models of governance, winning public confidence has hardly been a goal of successive civil and military regimes with some exceptions.

Under the Bhuttos, father and daughter, some attention was given to a redistributive or social agenda. But that was not significant to alter the structural gaps. Benazir Bhutto’s Lady Health Workers Programme perhaps is the best of these efforts, which has grown into cadres of more than a hundred thousand female primary health workers. Another state intervention that comes close to being pro-poor is the Benazir Income Support Programme that helps women in nearly seven million households. But these drops in the wasteful ocean of Pakistani state simply cannot bridge the disconnect between the citizens and the state especially when half the population of the country is disadvantaged in one way or the other. A recent study on multidimensional poverty by United Nations Development Programme holds that nearly half of Pakistan’s population is poor. If one adds the lack of citizenship rights to populations of tribal areas, parts of Balochistan and other ungoverned spaces, the cruel reality becomes even more unpalatable.

It is in this context that Edhi lived a remarkable life of attempting to fix a broken system. He made enemies as he relentlessly pursued his dream. The Mullah shunned him for giving equal treatment to non-Muslims, for being who he was a humanist. Edhi’s repeated references to humanism above the problematic of institutionalized faith angered the cleric even more. Even in his death some of those toxic voices made their presence felt. But the people of Pakistan once again rejected these state-fed, pampered proxies for state legitimacy. A religious political party offered his funeral prayers in absentia along with a young Kashmiri mujahid probably to equate the two or to moderate where Edhi stood in their eyes.

Among all the other charges leveled against Nobel laureate Malala, the most pronounced one was that she robbed Edhi of that accolade and the West preferred her to the humanitarian giant. Edhi was certainly above these titles and those who knew him or had the chance to work with him understand his mission in life. He did not seek honours but he sought a more benign, functional and humane society. While the state of Pakistan did the right thing to organize a state funeral to the great man, it would remain tokenism until the institutions of state turn themselves into people-friendly entities and reorient their misplaced, disastrous priorities.

It would not be out of place to mention elite opportunism at Edhi’s funeral. The saint who could care less about pomp and glory was bid farewell, in a disturbingly stratified manner, by the same civil-military elites whose greed and failures Edhi had been trying to rectify. Perhaps there was unstated gratitude. Or the age-old, desperately obvious appropriation of legitimacy. In his life and in his death, Edhi showed them the mirror. The sad part is that emperors seldom realize that they are wearing no clothes.

Beyond the buzz on mainstream and digital media, the celebration through popular culture and after the emptiness of state pronouncements, we need to ask the Pakistani state a simple question. How long would it need Edhis to render tasks that it has miserably failed to perform?