Miniaturist Saira Waseem is the latest exponent in a long list of Pakistani artists resisting the country political, cultural and social erosion.

Pakistani art going global is a remarkable story, for it typifies the ineffable contradictions of the country. In part it is a testament to the country creative expression, an explosion of sorts and partly a mode of resistance to the anti-art ideology that is permeating the social fabric. It’s not just painting or the booming art galleries, there is a revival underway of the moribund television drama, the resuscitation of cinema and continuous experimentation with music.

Salima Hashmi, a leading arts academician and practitioner noted in a recent essay that the proverbial worst of times are certainly the best of times for contemporary Pakistani art. Our foremost historian, Ayesha Jalal in her latest book The Struggle for Pakistan views the creative expression as a resistance to Pakistan forced Islamisation. Jalal writes:

The globalization of Pakistani music has been accompanied by a remarkable leap in the transnational reach of the creative arts a younger generation of painters are making creative uses of new ideas and technologies to both access and influence a diverse and dynamic transnational artistic scene. The dazzling array of new directions in the contemporary art, literature, and music of Pakistan displays an ongoing tussle between an officially constructed ideology of nationalism and relatively autonomous social and cultural processes in the construction of a national culture.

Jalal as a contemporary historian reminds us that the domestic battle of ideas and ideologies is not over and is assuming newer shapes. At the same time, the issue of a crumbling Pakistani state haunts the future trajectory. Is the arts and literature renaissance of sorts an antidote to a state unable to fulfill its basic functions such as securing the lives of its citizens? There are some immediate examples from the subcontinent that come to mind. The reigns of Wajid Ali Shah and Bahadur Shah Zafar in nineteenth century India were also remarkable for their artistic endeavours before the final takeover of the British. Not entirely relevant, these are important phases of our recent history to be remembered.

Pakistan blossoming arts scene, literature festivals and musical innovations notwithstanding, the country is bleeding; and not-so-silently imploding. Other than its global image problem, not entirely as fabricated as Pakistanis have been made to believe, the country is mired in a culture of denial. The delusions nurtured by its state, its intelligentsia and citizens are stuff that mythologies are made of. The greatest of such maladies is negotiating an identity for itself. The Islamic identity is now giving way to a sectarian one. No longer is it enough to be a Muslim, as the contest over who is a Muslim remains unresolved. In the 1950s, a judicial commission composed of Justices Munir and Kayani had highlighted this cleavage.

Keeping in view the several definitions given by the ulema, need we make any comment except that no two learned divines are agreed on this fundamental? If we attempt our own definition as each learned divine has done and that definition differs from that given by all others, we unanimously go out of the fold of Islam. And if we adopt the definition given by any one of the ulema, we remain Muslims according to the view of that alim, but kafirs according to the definition of everyone else.

Despite this clarity of thought, the political elites and military continued to use religion as a tool of politics and maximization of power. By the late 1960s, as enunciated by General Sher Ali Pataudi, a minister in Yahya Khan cabinet, the ideology of Pakistan (a vague concept) turned into a cornerstone of Pakistani nationhood. Citizenship and faith gradually became synonymous; and the rights of Pakistani people became more and more nebulous.

Pakistan Parliament, in a rather dramatic move, declared the Ahmadi community non-Muslim in 1974. In the 1980s, following the Iranian revolution, the official patronage of anti-Shia militias started. Since then, targeting of Shias has been on the rise and now the term Shia genocide earlier frowned upon by experts is entering into popular discourse. Iran, according to Pakistan official quarters, also sponsors groups in Pakistan but the majority-minority dynamic sets an unfavourable balance of power in this deadly game. By the early 1990s, in the relentless wave of Islamisation the country also amended its blasphemy laws and made them even more draconian. The Christians, among others, have borne the brunt of this law.

This trajectory of the country history has found resonance in contemporary art

This trajectory of the country history has found resonance in contemporary art as well. Saira Wasim, a gifted artist from Pakistan, now based in the United States, has continued to depict the state of her homeland (and its position in the world) through a candid and allegorical lens for the past decade and a half. She has rather remarkably, taken up taboo themes such as the naked hypocrisy of Pakistan leaders, the mullahs, and honor killings of women. Wasim has not spared the contradictory imperatives of global politics either and employed satire to lampoon US policies, especially under George Bush. This trajectory of the country history has found resonance in contemporary art to create a new kind of postmodern miniature.

Wasim graduated from the National College of Arts in 1999 and not surprisingly found international recognition soon enough. In 2003, her works were featured in a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In the same year she undertook a residency at the Vermont Studio Center. Since then the US has been her home.

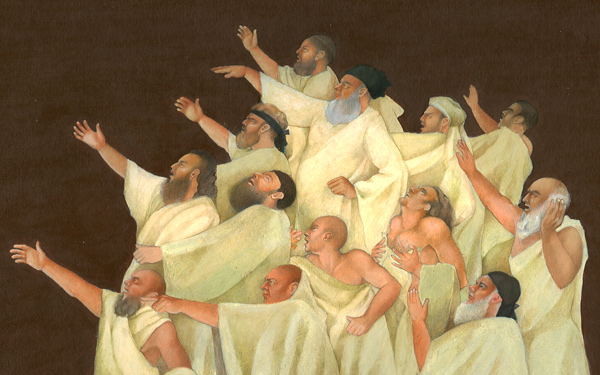

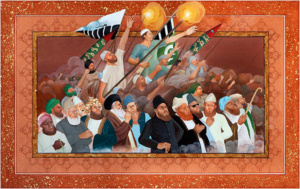

Wasim artistic expression is also influenced by her personal story. An Ahmadi by faith, she has experienced persecution and knows the intricacies of marginalization, and the hysteria for a puritanical patriotism. Her monumental work Patriotism set the trend of making art a powerful mode of resistance. This was before she migrated to the US. The miniature challenged the construction of religious nationalism by depicting a motely crew of Mullahs of almost all creeds and varieties waging jihad, and a group of armed young men following their creed.

The young artist, barely out of college was seeing it all and had the gift to document it in miniature format

This painting was completed before 9/11 and many in Pakistan who consider Pakistan predicament to be a result of the US War on Terror must see this chilling expression of national identity. The young artist, barely out of college was seeing it all and had the gift to document it in miniature format. Fifteen years later a good number of young Pakistanis have been confused by Pakistan rulers to the extent that violence always has a justification and the perpetrators are almost always foreign.

Wasim art transmutes into a powerful form of resistance to the mainstream ideology

Wasim therefore is an exile, a marginalized citizen of Pakistan and of course a woman who has come a long way. She had to challenge family conventions to become an artist. These layers of exclusion and struggle are evident from her choice of themes and ability to unpack exploitative coatings of contemporary politics and society.

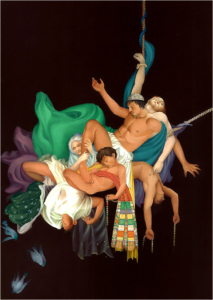

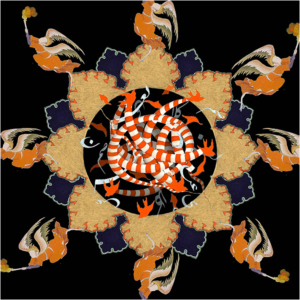

Throughout her work Wasim has employed allegorical references, almost like a traditional Persian and Urdu poet. But she told me that her familiarity with Western art gave her the idea to fuse ideas. Her meticulous craft and the virtuosity of portraits and scenes make her miniatures a visual delight. In the post-9/11 world, Wasim work turned comical but hid tragedies under that thin veneer of comedy. These tragedies were global, local and personal but never morose, as comic relief kept a little door open for hope and for redemption. The 2004 series, Passion Cycle, in minimalist terms, depicts a group of extremists who are both the leaders and the led, commenting on their version of jihad.

The evidently Mughal narratives in her work are re-crafted with a touch of photo-realism. Her works have lampooned Musharraf and his alliance with the West and well-known clerics in Pakistan are often framed in carnivalesque farces. The American version of globalisation gets a critique and so does its reaction: the various shades of Islamic extremism. In Ronald McDonald Comes to Your Town (2009), Wasim depicted the McDonald clown holding the American flag while riding on a liminal deity. Another important painting of hers in my view is called Identity? that narrates the tale of a global Muslim in the contemporary age. The miniature was completed after a Pakistani-American, Faisal Shahzad tried to carry out a terror attack at Times Square in New York in 2010. Wasim plays on the theme of identity as an American, Pakistani and Muslim. This painting is a reinterpretation of the 16th century Mughal painting, Nasrat-e-Jang (victorious in War). The figure Khan Dawan participated in or led major battles of his time to protect his country but spent much his life in spreading peace and shunning wars. The painting hints at American-Muslims patriotism and is also a humble plea to the social in justice, as Wasim told me.

Her series, Ethereal, comes as the most vivid and fluid narration of killings that religious minorities face in Pakistan

For me it is also a comment, a parable for the majority of Pakistanis who want peace but are viewed as violent. The image problem, as we say back home!

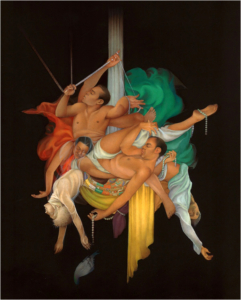

The most recent works by Wasim are a departure from the earlier trend. Perhaps jolted by the bad news from Pakistan, her series entitled Ethereal comes as the most vivid and fluid narration of killings that religious minorities face in Pakistan. In the three-part series, Wasim uses bright human figures in a fleshy tone against a dark background, representing the senseless murder of innocents. Colourful clouds hovering over distorted bodies bring out the silent madness inherent in the situation. Wasim says, the skin tone was highly important for me which represented the insane murder of all of humanity. Other than the obvious political commentary, Wasim technique plays with the use of Bouguereau The First Mourning painting, French neo-classical styles and even underwater photography.

In the tradition of miniature documentation, the historians of tomorrow would refer to these works as perhaps the testament of what was happening in the early part of the twenty first century in a country battling with itself. In the past decade when the confluence of global and local extremist ideologies took place in Pakistan, the minorities have suffered immeasurably. Since 2009, over 12,000 members of minorities have fled Pakistan in search for security. In its recently released annual report, Amnesty International says that in Pakistan, Religious minorities continued to face laws and practices that resulted in their discrimination and persecution

The persecution of Ahmadis, widely condoned in Pakistan, is a harrowing tale of marginalization

Shia Muslims have been the central target of militant groups. Only in 2013-2014, 54 attacks against the Shia community were recorded, resulting in the killing of 222 Shias. There were 22 attacks on the Christian community, resulting in 128 deaths. The persecution of Ahmadis, widely condoned in Pakistan, is a harrowing tale of marginalization. Each year, dozens of attacks lead to target killings and the burning of homes. After the deed is done, there is little or no condemnation in the country. Wasim is their artistic oracle, fusing the sublime with the violent and the ethereal with the ordinary.

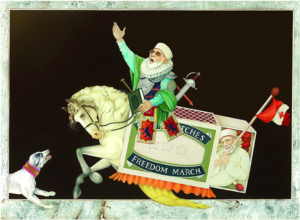

While she was musing Ethereal, her tragicomic style expressed itself in the form of the Divine Comedy series. The most iconic of these included the reference to a Canadian-Pakistani cleric leading a political movement. The symbolism of that miniature cannot be lost on us. The antics of the so-called movement in the summer of 2014 brought Pakistan to a standstill exposing all the contradictions of the message, the leader and the rhetoric that was televised. While compromised sections of Pakistani opinion were branding a new messiah, miles away Wasim chronicled in a small frame, an otherwise complex and lingering story.

For all its finesse and stylistic innovation, Wasim art transmutes into a powerful form of resistance to the mainstream ideology recycled by Pakistan power elites. The key question is, could she have done all of this while in Pakistan. It is true that many artists are doing that in Pakistan too. Imran Qureshi for instance has been producing brilliant critiques of society and its cultural symbols and Rashid Rana has taken his commentary to the global level by directly confronting globalization and its uneasy relationship with Pakistan.

Yet a blasphemy case against an art magazine, its editors and writers and of course its painters, hangs in the air. Artistic freedoms in Pakistan are curtailed but also perennially resisted. Not unlike its history and genesis, Pakistan future remains open to interpretation. One thing is clear: The creative spirit of Pakistanis, at home and abroad, is not giving up. Not anytime soon.