He wanted variety and could not confine himself to a uni-dimensional career or vocation. Other than being a rare blend of East and West, Patras exemplified the modern man, searching for new meanings in life and experimenting with experiences

This December witnessed a literary landmark of post-internet Pakistan.A dedicated website www.patrasbokhari.com on Patras Bokhari, a towering literary figure, was launched at the Government College University, Lahore. It is well-known that the GC produced world-famous personalities while it was the leading educational institution in this part of the subcontinent, but its stature as a hub of education, culture and literary regeneration declined over the years. Some observers hold, however, that the recently increased autonomy and elevation of GC to the status of a university will reverse the decline. It was the glorious tradition of this institution that produced giants such as Patras, Faiz and Iqbal, amongst many others.

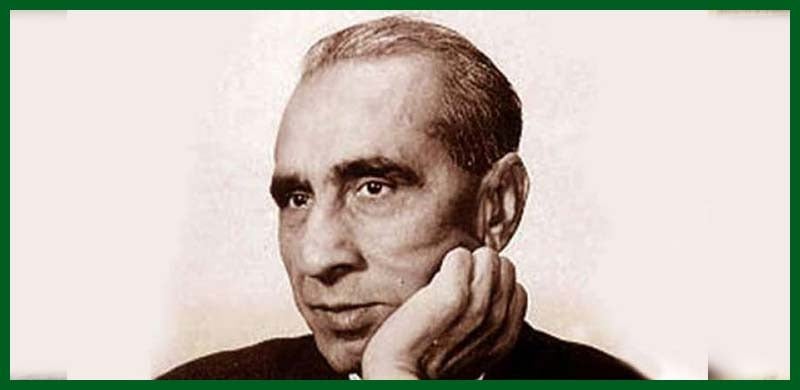

Prof Syed Ahmed Shah Bokhari (1898-1958) is most famous through his penname “Patras” Bokhari. While he was a first-rate educationist, broadcaster and diplomat, perhaps his lasting fame is the result of his stature as an inimitable essayist and humourist, a rare trait amongst the mourning and elegy-prone South Asian creed. Patras Ke Mazameen , immortal as they are, set the standard for high quality, incisive satire and humour. Unlike the medieval mores of literature being the preserve of the courts and its courtiers, these essays reach out to everyone, encompassing a modern sensibility that makes them pertinent and attractive even today. There is a distinct universality in these writings that perhaps had to do with the humane and cosmopolitan side of Patras himself. The compelling evidence of this aspect was his huge success as a diplomat when he served as Pakistan’s permanent envoy at the United Nations in the early 1950s, enabling him to be titled ‘a citizen of the world.’

Patras has, however, been criticised for being a man without a vocation and one who did not adequately focus on his literary genius. Lionel Fielden, who facilitated Patras’ career shift from teaching to broadcasting, remarked: “He was much more the don than the impresario, and broadcasting needs the impresario, which his brother was. I did not really want Ahmed Shah to succeed me when my contract finished because I thought, despite his brilliance, he was the wrong man for the radio.” Allama Iqbal is purported to have composed the poem Aik Falsafazada Syedzaday Kay Naam on his disappointment after meeting Patras upon the latter’s return from Cambridge, Iqbal had earlier provided Patras with references to Cambridge. Others complained that he did not focus on literature: “He was a majlasi aadmi and loved to be with people. Perhaps the lonesome existence of a scholar was not in keeping with his temperament.”

Noon Meem Rashed, a student, lamented that Patras was “.. . a great man who missed the bus. The buses passed by one after the other, while he kept looking under his feet. For example, writing was his forte and among his countrymen he will always be remembered and respected as a writer, rather than as an administrator or diplomat; but he did very little to apply himself seriously to writing and once he sold his soul to the demons of administration and diplomacy, so to say, he found it even harder to satisfy his urge to write.”

These subjective evaluations seem to be unfair to such a diverse soul as Patras Bokhari. During his short life, he seems to have been the figure around whom rallied luminaries such as Taseer, Chiragh Hasan Hasrat, Ghulam Mustafa Tabassum, Noon Meem Rashed, Faiz Ahmed Faiz and many others. Patras provided critical and creative encouragement to so many who touched his life. He wanted variety and could not confine himself to a uni-dimensional career or vocation. This is what makes Patras different from so many of his contemporaries.

Other than being a rare blend of East and West, Patras exemplified the modern man, searching for new meanings in life and experimenting with experiences. His Mazameen are a rare gift to posterity and no wonder they remain as popular as they were when published decades ago. Lahore ka Jugraphya and Mable aur Mein are evergreen classics in their own right. In true South Asian tradition, we are averse to change; the many shifts in Patras’ career must have irked his more traditional contemporaries. Nevertheless, he shone within his country and abroad and brought much honour to Pakistan.

Professor Anwar Dil’s collection of Bokhari’s speeches and writings On This Earth Together, Ahmed S Bokhari at UN 1950-58 is a valuable contribution to understanding the prolific figure. Dil’s laborious task of compiling scattered papers pieces together a varied man. To date, it is the only book of its kind.

Journalist Khalid Hasan once commented that “Bokhari was a highbrow.” At the UN, he returned a poem sent for a campaign by Robert Frost, as he did not think ‘it was up to par.’ In his book Diary of a Diplomat published in 1986, Afzal Iqbal records several real-life anecdotes that testify to Patras’ ‘pure humour,’ the freshness of which prompted Gilani Kamran to say that Bokhari’s voice and style was something new in our literary tradition.

While talking of Patras, one cannot but mention KK Aziz, the eminent historian who was a student of Patras. In his love for his teacher, Aziz established the Bokhari English Prize at Cambridge University, awarded annually to the best student of English at Emmanuel College (making him the first Asian in whose name an endowment fund has been established at Cambridge). I remember reading an account of Aziz being overjoyed to discover Patras’ photos at the library of Emmanuel College. KK Aziz has been working on a seminal biography of Patras and we all await its completion.

Despite his status of being nearly a household name in Pakistan, by all accounts, work and research on Patras remains limited. We are not known as a nation that preserves its heritage or passes it on to the younger generations through accessible routes. Patras’ grandson Ayaz Bokhari and his associates have done a tremendous job in constructing the website and, in so doing, breaking the near silence on Patras.

The well-designed, user-friendly website was officially launched at the GC University on December 24, 2005. Thankfully, the links open with relative ease and the handiwork of Pakistan Data Management Services appears to be of a professional quality. There are some great photographs and features on the site. At the launch, Ayaz Bokhari rightfully commented that “access to knowledge (in Pakistan) remains limited and restricted. I decided to set up a website comprising the works and life of Patras Bokhari, to try and collate as much as possible in one location for free access to all, with the hope that the children of our society do not face such a difficulty, and that this might stimulate more work of such nature by others.”

The evolution of this website is also interesting. Emanating from the school projects of Ayaz Bokhari’s children, the idea became bigger and eventually led to a full-fledged web resource, perhaps the only one of such a comprehensive nature, on any contemporary Pakistani literary figure.

In the words of Ayaz Bokhari, “the question before us is: what are we, as Pakistani society, doing to communicate the works of our intellectuals, scholars, men of letters, our luminaries in various fields? Are we, as a society, making a fast enough transition from word of mouth or print to the electronic media? I fear not. I sincerely hope that this will prompt the development of more websites to capture and present the works of our luminaries for easy, free and ready access by all.”

Patras’ grandson has shown the way to many others by setting a standard for many of the real and imagined successors of our great literary and cultural figures. The internet and its related tools can be powerful sources of the transfer of knowledge to Pakistan’s future generations. We have already reduced the size of our libraries, while printing and publishing is an endangered business. Whether we like it or not, more and younger Pakistanis will be hooked onto the Internet, the number of users has already crossed 20 million.

This winter has reinvigorated Patras’ memory. While I am confident that the website will be well-received, it must grow beyond its present limits. Patras’ rich life has many facets waiting to be brought into the public domain. EM Forster summed it up very well: “Many can shine in the universe but only few can shine from the darkest of eclipses, and Bokhari is one of them.”

Treading the halls of diplomacy

Born in 1898, Syed Ahmed Shah ‘Patras’ Bokhari was a distinguished student at Lahore’s Government College (GC). He made his mark on the institution’s dramatics scene, including playing Hamlet in what was arguably the best effort of the college’s dramatic club, and by editing the college magazine The Ravi . He stood first in his year for the MA English examination and later taught English as a lecturer, juggling alongside a flourishing acting career.

In 1927, Patras started a degree at Cambridge University, from where he earned a First in his Tripos, in itself is a rare distinction. On his return from Cambridge, he started teaching at the Government College as a full professor. Patras’ career did not remain restricted to teaching; before long, he named and became involved with the All India Radio (AIR). His distinguished brother Zulfikar Bokhari was selected as the Station Director, while Patras was appointed the Deputy Director General of AIR. In time, Patras Bokhari became the Director General of AIR, when he identified and promoted several talents such as Noon Meem Rashed, Manto and Pran Chopra amongst others. In 1947, Patras, reportedly reluctantly, joined the Government College as principal, just as partition riots were breaking out. He remained at this post till 1950, inspiring a multitude of his pupils at GC.

When Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan went on a tour of the US in 1950, he took Patras along as his speech-writer. The speeches were later published by Harvard Press in the form of a book and were greatly appreciated for their quality.

In 1951, Patras was appointed as the Permanent Representative of Pakistan at the United Nations for his unique gift of being fluent in the worlds of the East and the West, in addition to his skills as an orator, a crucial requirement for diplomats. For the next four years, Patras represented Pakistan and established the tradition in the Pak-UN mission of advancing the cause of Muslim countries and peoples. His historical speech on Tunisia in the Security Council, against the Anglo-French veto on the discussion of Tunisia’s freedom, is a legendary defence of the emerging nation. Later, Tunisians named a road after Patras Bokhari. Another memorable address that Patras delivered, in the The New York Herald Tribune in 1952 on the problems of underdeveloped countries, is still a valid argument for the transfer of technology to underdeveloped countries.

His landmark speech at the UN General Assembly, welcoming the new secretary-general Dag Hammarskjold in 1953, led to another rise in his UN career. In 1955, the Secretary General appointed him the Under-Secretary-General in charge of public information. A glowing tribute came from Ralphe Bunche, Nobel Laureate, also an Under-Secretary-General at the UN: “He was in fact a leader and a philosopher, a savant, indeed, even though not old in years, a sort of elder statesman. His true field of influence and impact was the entire complex of the United Nations family.”

Other than his UN successes, Patras Bokhari was a sought-after speaker in New York and his articles in The New York Times provided him with increased stature, especially as the newspaper extolled his intimacy with Persian, Urdu and English, his extraordinary conversation skills as well as his lifestyle.

Diabetes, however, was progressively weakening Patras Bokhari’s heart and his health grew frailer. His career, still short of its peak, was cut short by his death in December 1958. He is buried in New York, and his epitaph, lines written earlier in his honour by Robert Frost, reads:

“Nature within her inmost self divides

To trouble men with having to take sides.”

RR