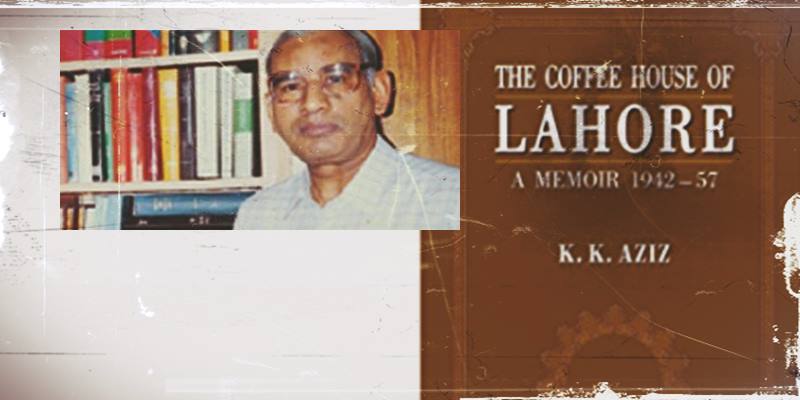

Before his death in July 2009, KK Aziz had accomplished one mission that he had set for himself, i.e. to write about the Lahore Coffee House, the glorious nursery of ideas. Luckily, despite his failing health, Aziz finished a draft that was meant to be a shining part of his autobiographical kaleidoscope. The Coffee House of Lahore: A Memoir, 1942-57 was published in 2008 and Aziz, in the opening chapters, tells us about the genesis of his passion to document this memorable phase of our contemporary history.

Whenever an intellectual, cultural and literary history of Lahore (or the Punjab and Pakistan) is written, the diverse circles which met and discoursed in the Coffee House will have to be described in detail and the ever-widening waves of their influence recorded. As nothing has been written so far on the subject and I don’t see anything in the offing, I give below a list of the important persons who I can recall.

Quite diligently, Aziz sets forth to list two hundred and six names that would include a wide array of thinkers, scholars, artists, writers and even some CSPs who obviously changed their life course despite the influence of their Coffee House days. For those who want to know about Lahore and its not-so-old diversity, KK Aziz’s memoir is a must-read. It is perhaps the only serious work on this important institution. Aziz has rightly mentioned in his book that the names he lists and the personae he describes in his biographical sketches aim to achieve four objectives.

First, that such a remembrance proves the ‘age of talent’ as it existed in Lahore. Second, a faithful picture of Lahore in the 1940s and 1950s emerges from the text. Third, that it provides the cultural historians of the future with a primary testament; and finally at a personal level, it shows how Aziz the historian and thinker was influenced by this exciting and vibrant milieu. During the early part of the 20th century, Lahore emerged as perhaps “the most highly cultured city of North India”, to quote Aziz. With a wide range of educational and cultural institutions and a composite society comprising all faiths and religions and political ideologies, the Lahore of today is no longer what it once was.

This eclectic mood of Lahore was best captured and represented by the Coffee House. As Aziz tells us, the Coffee House was “for over 30 years, the single most important and influential mental powerhouse which moulded the lives and minds of a whole generation, and its legacy affected the careers of the succeeding generation”. It is odd that the tea-drinking British were to introduce coffee houses in India. Aziz takes us through the history of coffee-drinking as to how it inspired the world to switch to coffee as a beverage of intellectual invigoration. One aspect that he omits is that coffee drinking was popularised by the Sufis who found the drink conducive to their meditation and mystical elation. It is said that in the 1930s, the Government of India created a Coffee Board to promote the sale and consumption of coffee beans which were grown in South India, and hence a coffeehouse was established in every large city of the Indian subcontinent. Aziz comments that this was also the period of a resurgence of communism and the rise of the Progressive Writers’ Movement.

The British were tea-drinkers, so were the Russians and the Chinese. But the leftists chose to issue their exhortations over a cup of coffee. Even the otherwise cataclysmic partition of India in 1947 could not break this radicalism-coffee bond.

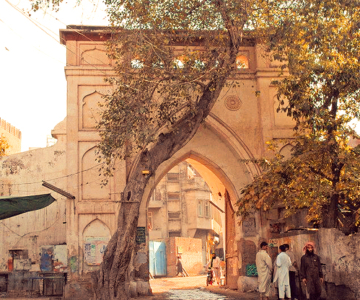

Thus in Lahore, the India Coffee House and India Tea House, situated 150 yards apart, became the two most popular meeting places of the literati and the radical intellectuals. Little wonder that Aziz states that the Coffee House of Lahore, “entertained more leftists than I found on the Communist Party office on McLeod Road”. We find out from the book that before 1947, the leftist visitors of the Coffee House included luminaries such as Sajjad Zaheer, Syed Sibt-e-Hassan, Abdullah Malik, Safdar Mir, Zaheer Kashmiri and many others. The Coffee House changed many sites but remained at the Alfred building till the end. Its old site, off Mall Road, was later the location for Pak Tea House , which survived until the turn of the last century, before commercial imperatives became paramount and intellectualism had to be abandoned in favor of greed.

The best part of this book, of course, is plain writing that sketches the lives and personae of its regular habitués. For instance, my favorite, Safdar Mir, the towering intellectual of our times, finds a prominent place in the narrative. Aziz paints a rather intimate portrait: unafraid of authority and uneducated public opinion, he spoke his mind freely and persuasively. While a lecturer at the Government College, he had his head shaved and smiling down the frowns and boos of his 2nd-year students, continued to lecture calmly and suavely. He was the best-read journalist of his age, and I know no other man whose reach and understanding encompassed so many fields: English, Urdu and Punjabi literature, Marxism, politics, the way a society works and modern history. His hall-mark was a resounding laugh which could be heard three rooms away. His eyes glittered with merriment behind his thick lenses while narrating a funny story or narrating a point in his argument, as if throwing a challenge to his audience to produce a better one.

While browsing through the book, other eminent habitués of the Coffee House also came to life. Men of letters, such as Chiragh Hassan Hasrat, Zaheer Kashmiri, Aashiq Hussain Batalvi, Syed Abid Ali Abid (whose biographical sketch is candid and a wee bit un-sparing) are found walking on the streets of Lahore, sipping coffee at their favourite joint and indulging in the world of ideas and discourses.

The death of the Coffee House and the burial of Pak Tea House have coincided with the demise of discourse in Pakistan. We have done well to acquire nuclear weapons and thousands of madrassas that preach violence and hatred. But we have lost a culture that was based on tolerance, peace and amity.

KK Aziz has done a great service to Lahore, Pakistan and the Indian subcontinent by documenting an era that will never return.