One of my three reports published earlier this year in Herald’s annual issue on heritage

Lahore fabled Walled City is now a grand metaphor for the tragic neglect of heritage. Over the years, it has turned into a business district as residents increasingly head towards the anonymous suburbia. The population of the Walled City has declined during the last two decades: every passing day witnesses the undoing of a past lovingly built over centuries.

Created by the Sultans of Delhi in the 11th century, the Walled City soon emerged as a major centre for Muslim culture in the region. During the reign of later Sultans, Lahore suffered regular invasions and pillage until, after Babur invasion of India in 1526 when it was ransacked and resettled. Sixty years later, it became the second capital of the Mughal Empire under Akbar and, in 1605, the fort and the city walls were expanded to their present-day dimensions. Emperor Akbar spent seven years in Lahore and his son and successor Jahangir was a proud resident of the city. By 1662, Lahore was reportedly surrounded by a 15-foot high wall that had 13 gates for entry. Brick by brick, the wall withered away over the next three centuries. By 1947, it had completely disappeared.

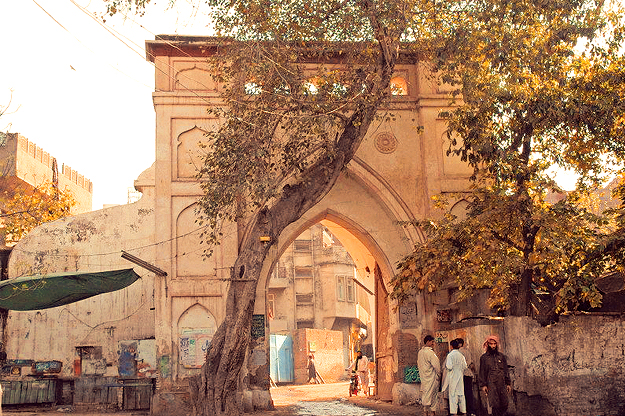

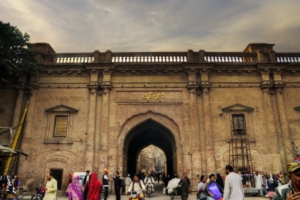

Lahore 13 gates and the walls survived in their original shape until the 19th century. During the Sikh period, these city walls were repaired and maintained. An outer perimeter wall was also built. Much changed after 1857 when the British demolished almost all the gates in order to de-fortify the city. Some were rebuilt later in simple structure except for Delhi Gate and Lohar Gate which were somewhat more elaborate. The Shahalmi Gate was gutted during the horrific communal riots of 1947 and the Akbari Gate was demolished for repairs but never built again. Out of the 13 gates, only six Bhaati, Delhi, Kashmiri, Lohari, Roshnai and Shairanwala survive. The majorit are in a sorry state of disrepair.

While the Pakistani state weaves fiction around Muslim ascendancy and proclaimed Pakistan a fortress of Islam, its ruling classes have displayed a callous attitude towards the country physical heritage.

Rampant, unplanned commercialisation has taken place I areas rich in architectural heritage. In 1950s, the Lahore Improvement Trust (now known as Lahore Development Authority) endeavoured to undertake well-planned commercial development projects but its attempts were far from successful. During 1970s and 1980s, nearly 29 per cent of the residents are estimated to have left the Walled City.

During the last two decades, the Walled City has become even more commercialised, polluted and damaged.

Everywhere, old houses and havelis are demolished to build commercial and residential structures which are incongruous with the overall layout and aesthetics of the area. Most of the inhabitants in the Walled City are wholesale businessmen in search of storage space, often assisted by a new group of Afghan refugees who provide relatively cheaper labour.

Urban planner Imrana Tiwana explains why it is important to restore the city to its former glory. Context is essential in historic cities like Lahore which have stood as a testimony to time. A concerted effort needs to be made to steer away from the tacky and the superficial, which will gradually destroy the integrity and dignity of the old fabric. This insensitive tampering in the Walled City is beginning to irreversibly destroy the city. In 1980, the Lahore Development Authority Conservation Plan for the Walled City of Lahore identified 1,400 buildings within the Walled City that had high architectural and historical importance and also presented several proposals for conserving them.

Subsequently, the World Bank-funded Urban Development Project was initiated, which made some improvements in the physical structure. However, it could not achieve the goal of reforming the urban and municipal institutions that play a critical role in the conservation of urban heritage.

A key achievement of these efforts was the restoration of the Wazir Khan Hammam (bath house), built in 1638. Travellers to Lahore used the hamam to refresh themselves after a long journey. Commonly known as the Shahi Hammam and built using brick tiles and limestone cement, it is the largest Mughal bath house in Pakistan, spread over 1,110 square feet. Its restoration of the hammam was part of a collaborative effort between the Punjab Archaeology Department and the Tourism Development Corporation of Punjab, the latter provided funding. As a result, its domes have been re-plastered and its floors lime-terraced. The stunning fresco work in the hammam represents the best of Indo-Islamic motifs while floral patterns and angels indicate Central Asian influences. Today it is one of the few tourist centres of the Walled City. The bath houseremains an importantsite due to its location at the busy Delhi Gate entrance, which lead to some of the most significant monuments within the Walled City.

In the last few years, the Punjab government has embarked upon another effort to conserve the Walled City: the Sustainable Development of Walled City Lahore (SDWCL) commenced in 2006, once again with the support of the World Bank. In July 2007, the provincial government signed the Public Private Partnership Framework Agreement with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), Geneva, for cultural heritage conservation. The AKTC has a celebrated Historic Cities Programme which has aided conservation in such diverse contexts as Egypt, Syria, Bosnia, Mali, Zanzibar and the Gilgit-Baltistan areas of Pakistan.

The first site for restoration work in Lahore is Shahi Guzargah (The Royal Trail), a street that is 1.6 kilometres in length from Delhi Gate to Masti Gate next to the Lahore Fort. Out of a total of 3,800 commercial units in the locality around the street, 955 are situated along this trail. In addition, there are 2,490 housing units in this area. The heritage assets along this trail include the Shahi Hammam, Masjid Wazir Khan, Sonehri mosque, Baoli Bagh and Maryam Zamani mosque. The entire route from Delhi Gate to the Lahore Fort is to be restored through the rehabilitation of monuments and upgrading of urban infrastructure. This project is thus focused on what is thought to be the soul of Lahore.

The work on SDWCL has been slow but some initial studies have been completed. Tania Qureshi, a communications expert at SDWCL, explains that the project has so far conducted key baselines studies, demarcation of right of way in the Walled City, the completion of conceptual designs of the entire Walled City, topographical and Geographic Information System studies including the restoration of model streets. Other tasks envisaged include the difficult issue of removing encroachments, repairing the trail, improving the water supply and solid waste management and setting up underground electrification. Introducing building control by-laws and regulating traffic are likely to be more difficult. Naheed Rizvi, who heads SDWCL, says, “The area is very difficult and narrow to work in. Most of the work has to be done manually as we cannot use machines. The removal of encroachments is also difficult. However, the World Bank has provided a Resettlement Action Plan to minimise displacement grievances as much as possible. When businesses are removed, they are compensated.

Rizvi recounts how locals were suspicious or at best dismayed by the many delays in the implementation of this project. But as we have worked there residents have increasingly started supporting the project. Initially to allay the fears of residents, we did a successful demonstration restoration. This was the restoration of Gali Surjan Sing, Chak Garah and Mohammadi Mohalla. Traders, however, are still not pleased with the project due to their commercial interests taking priority over community interests. In fact, even though the demolition of buildings has been banned by the city government, we have seen overnight demolitions happening with foundations for new plazas appearing in the morning.

I visited the restored streets and the work on site was quite encouraging. However, it is only a minor segment of the whole complex. More than half of the heritage assets have disappeared. Critics of this initiative, such as architect Kamil Khan Mumtaz, challenging the ethos of this project argue against the paradigm of modernisation and urge it be replaced with a vision for indigenous development which is inclusive and calls for redistributing wealth, focusing on public health, including local voices and emphasising, not undermining, tradition.

In 2009, the Punjab government shut down the acclaimed Gawalmandi Food Street, just outside the Walled City, mainly because it was created by the previous provincial regime opposed to the incumbents.

Now a new street at the edge of the Walled City is being built at the Fort Road. Most of the work has been completed and, unlike Gawalmandi Food Street, there is no political opposition to this project. However, putting food at the centre of conservation work, or even ahead of it, as is the case with food streets, betrays another kind of debasement. Some experts, therefore, are opposed to the idea of setting up a food street right next to highly important monuments such as the Fort. True, bringing foreigners and the affluent to this area might draw more attention to the jewels of the city but food alone cannot substitute for integrated cultural development.