Raza Rumi was fascinated by artist Aasim Akhtar’s unique curation of Pakistani textile heritage at the Rawalpindi NCA – Click here to see more:

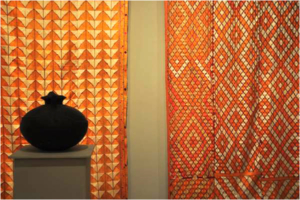

A recent exhibition in Rawalpindi showcased the rich variety of traditional textiles lovingly weaved tales from the various corners of Pakistan. Aptly titled, Vanishing Worlds, Enduring Threads, it presented a wide collection of textiles collected by artist and writer Aasim Akhtar. The threads, which Aasim had labeled as enduring, are disappearing fast, overtaken by mechanization, changing aesthetics and economic patterns. The exhibition was curated at the Potohar Art Gallery at the Rawalpindi Campus of the National College of Arts (NCA).

I was lucky to have the collector-curator walk me through the pieces on display, my instant reaction to which was how could anyone collect such a large variety and then keep it safely. One has to be as dedicated, eccentric and involved as Aasim to have picked up the best from villages, goths and remote corners of the country and create a formidable ensemble after two decades. From the better-known forms such as phulkari to chunri, the exhibition had some dying forms such as lungi and animal trappings.

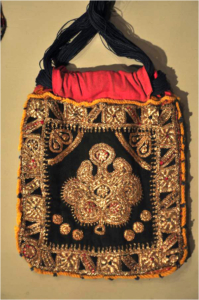

Aasim explained how men and women of multiple ethnicities possess a textile heritage of incredible abundance, and truly this is the known and hidden, rich and lived culture of Pakistan. Vanishing Worlds thereby is a tribute to Pakistan’s diversity and aesthetics which have informed everyday lives of multifarious communities. In fact, the folk textiles were hardly created for commercial purposes: they were inter-generational methods of passing on heritage and often treated as family assets. For the most part, women who created these fabulous designs and forms were preparing for their children’s dowries, and the presence of these intricate pieces of cloth testified to the skill and wealth of the family in question. Aasim informed me that embroidered heirlooms were a measure of prosperity, and marked the identity of the user, his/her community and traditions. The motifs, colours and styles were identifiable codes of the community.

The collection also showcased some extraordinary Phulkari work. Phulkari literally means flower work a rural tradition of crafting embroidered head covers or shawls. While these shawls are embroidered in Hazara, Chakwal and many other parts, the most well-known Phulkaris are from Swat and other parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Aasim’s collection was also from this region. The old pieces showed the intense labour that must have gone into the preparation of these designs. The other surprising textile work was women’s elaborate dresses with embedded silver work from Kohistan, an area of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. Kohistan, otherwise in the news for its conservatism and more known for its images of tortured women, appeared to be a region full of beauty and gentleness in this work. The women’s long shirts and loose trousers resembling the dhoti shalwar of the 80s had numerous motifs on them. Kohistani traditional dresses also have intricate silk embroidery, copper buttons, metal roundels and curious beads. The hand-woven black cotton fabric shares the larger regional tradition. From Afghanistan to this area, the black material is used with similar use of beads, metals and motifs rooted in the bounties of Nature.

The most striking part of this exhibition was the animal covers from Sindh and Balochistan. In nomadic communities, the livestock comprises real assets and friends of communities. Thus the painstakingly prepared horse-head-covers and camel trappings were outstanding. Our people have such delicate tastes and as Aasim told me that communities continue to preserve this tradition from one generation to other.

Over time these traditions have come under attack by rampant consumerism. Several such gems are now found in affluent homes of wealthy Pakistanis here or abroad, through an elaborate network of middlemen, sellers and dealers. These radical shifts are changing the traditional patters of folk textiles as the products lack their earlier familiarity and intimacy. Prepared for markets the materials used have also changed over the decades. Leather, for instance, has now been replaced by plastic, wool with acrylics while natural dyes have almost vanished. This is why the exhibition’s range of natural dyes from Hazara textiles to those prepared in Sindh was a reminder of a fast vanishing skill.

Most importantly, the textiles on display also reflected how communities and households used to scarcity created art in their everyday lives with local-natural materials and household labour. The folk roots of Pakistani textiles are also a testament to the thousands of year old civlisational history of the Indian-Pakistani subcontinent. In this region, wild cotton was processed into woven cloth and there was as abundant use of indigo that created a unique aesthetic. It should be remembered that indigo was one of the major exports of ancient India and several fortune hunters in this region came for these local products. The early trade of spices and dyes from India shaped our history.

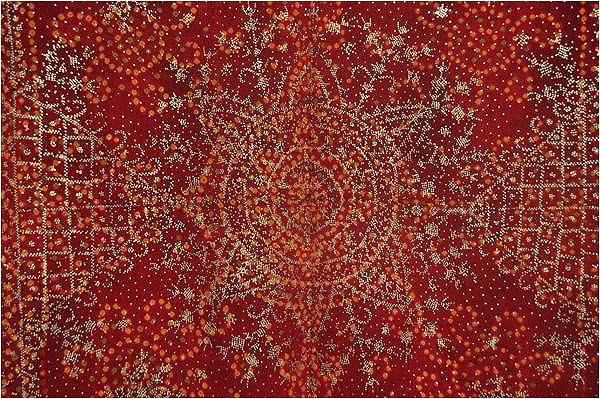

Textiles from Sindh are notable for their colours and patterns. Two most unusual rallis in Aasim’s collection were distinctive or their sheer rustic beauty. Rallis (or quilts) are made in Sindh, Balochistan, Cholistan and in the southern borders of the Punjab province. Ralli literally means to mix or connect perhaps derived from ralaana or ralnaa. In many parts of rural Pakistan and bordering Indian states, rallis were symbols of wealth in a girl’s dowry. The process of Ralli-making is quite complicated: Cotton fabrics are first dyed to the required color and then they are weaved into patterns (usually squares or rectangles) to create a diverse impact.

Other gems in the exhibition were pouches created by different communities for multiple purposes. These small products had detailed patterns and unique motifs depending upon their use. Other items on display also showed the fusion of various subcultures. For instance a small hand embroidered textile from Rahim Yar Khan (a town of Southern Punjab) mixed Baloch and Sindhi patterns of embroidery especially their delicate stitches and mirror-work.

Walking through the gallery at NCA was an intense journey into the living art traditions of Pakistan. I had no idea that the Hazara area had such a fine tradition of fabrics especially for the use of men. Several items especially lungis and turbans on display were prepared for bridegrooms using natural dyes and startlingly bright colours. It is a pity that we have almost no avenues to showcase these traditions to build an appreciation of Pakistan’s folk art.

Aasim’s collection was curated with much thought. There were creative spaces between the textiles to ensure that the details and impact were highlighted. One can only marvel at a collection that covers the most diverse range: Embroidered textiles, naturally dyed and hand-woven textiles, and non-woven textiles. As a keen student of folk heritage this display tells the larger story of vanishing crafts and cultures. We spoke about a permanent display and agreed on a few venues in the international arena. Sadly, Pakistan has very few places where textile-heritage has been properly curated or preserved. A treasure in the Lahore museum has been a victim of neglect and official apathy and as Aasim said some of the items on display there are permanently damaged.

It would be tragic if Aasim’s collection moves abroad or is sold to private dealers. It belongs to Pakistan and its posterity, as the skills, materials and traditions are vanishing, to use the collector’s word. Perhaps there has to be some effort by the private sector if the state cannot provide the necessary support. At the same time, it is essential that these are on display. Ironically, our heritage is safer outside Pakistan. In our museums and archaeological sites, lack of appreciation has led to major theft, smuggling and decay. Culture and saving heritage has never been our priority. Let’s hope this changes soon.