Farzana’s brutal murder represents all that is wrong with us.

It has become a useless routine to condemn the most ghastly acts of violence and injustice in Pakistan. For many, these are daily occurrences and thus the levels of desensitisation have grown. So has the brutalisation of society, when it adapts to some bare facts and upholds and sometimes celebrates the worst of what constitutes custom, tradition or culture. What else would explain the fact that there were dozens of passerby near the Lahore High Court known for its imposing architecture and not the delivery of justice now who silently witnessed the death of a woman scorned for choosing her partner? Worse, the police did not intervene either. This has become the norm with what we know as the state in Pakistan. It chooses to remain indolent, indifferent and even complicit at times. This has left the citizen vulnerable. The weaker you are, the more chance there is of your life meaning absolutely nothing.

A few weeks ago, I underwent the worst of nightmares. Seeking help on a roadside with two wounded men: one almost dead and the other struggling to stay conscious. My romanticism for my own country was shattered on that fateful night of March 28. I am privileged and lucky that I escaped a brutal, unsung death but a life was lost. A large crowd had gathered to ogle at the blood sport but none of them was willing to help in taking a near-dead body out of the car. On a busy street, no car was willing to stop to take my injured driver to the hospital. Farzana’s death and her calls for help have only reopened my wounds far from healed and as painful as before. This state of our society, drunk on honour, pride, ghairat and other medieval notions of self-worth, has crossed all tolerable levels of dysfunction. Yes, two girls were also hanged, allegedly gang-raped in India, and crimes against women are prevalent in other societies as well. But, at least, there is collective uproar, pressure on the governments and results.

In our case, it took the prime minister 48 hours after the event to take notice and to date, the head of the Punjab government, otherwise celebrated for his style of governance, to even condemn the barbarity in a city that he intends to turn into Paris. With all the Metro Buses and fast rails, twisted highways and expensive underpasses, there seems to be a breakdown of the social fabric. Wanton violence and a high-level tolerance of lethal outfits, their affiliates and dozens of sleeper cells, make a mockery of the shining Punjab story.

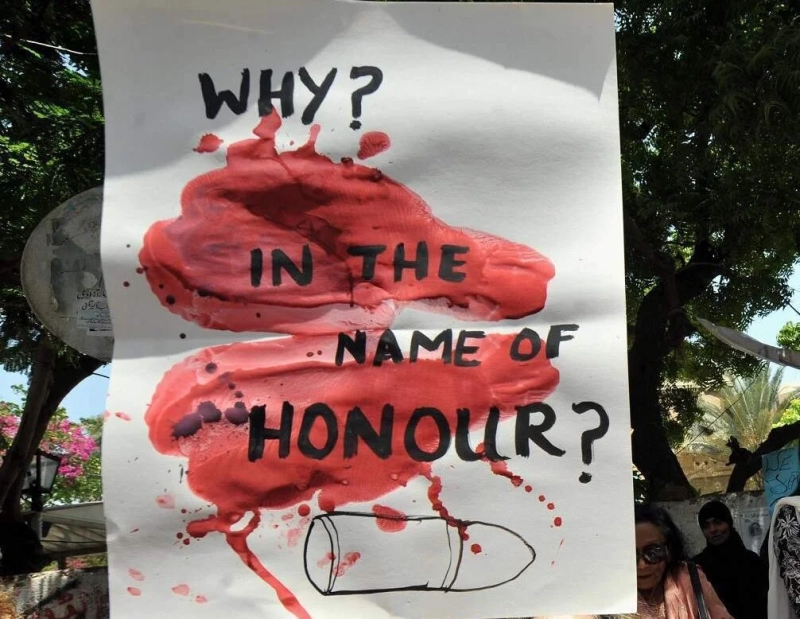

Farzana’s case represents all that is wrong with us: from the misuse of a faith-based legal system that forgives the murderer, to embedded misogyny and the stark absence of a state that is supposedly there to arbiter citizen protection and welfare. Farzana’s husband had murdered his first wife to marry her. Her sister also became reportedly a victim of honour killing and nearly 1,000 women reportedly are killed in the name of custom and tradition that is founded on a spectator sport where women, minorities and the marginalised are killed with impunity.

Take the case of Dr Mehdi Ali, an American-Pakistani doctor volunteering in Pakistan. He was shot dead in front of his family (a child included) with more than 10 bullets. And the high and mighty of this land cannot even acknowledge that he was gunned down since he was an adherent of a faith that Pakistan’s political and religious elite shunned through a constitutional edict. Exactly 40 years ago, Pakistan’s state officialised discrimination on the basis of faith by declaring the Ahmadiyya community non-Muslim. Sadly this happened under a civilian government backed by a political consensus. Dr Mehdi Ali’s murder and the brazen killing of nearly 90 Ahmadis in 2010 are but a continuum of what was decided by our elected leaders, the religious guides and of course, sections of the press. To say that killers don’t get apprehended or punished in these cases is to in fact miss the larger picture. They cannot be in a society that has been engineered by the state since the 1970s. This is why condemning an Ahmadi’s murder is somehow viewed as approving of their faith by the hardliners. Hate speech is no longer recognised as such. It is the norm, the correct worldview in a collective quest for mythical purity.

There is cleansing underway now except that it has engulfed everyone in it. Shia genocide, attacks on Christians and Hindus, targeting of Sufi shrines, almost everyone is a target of the rival armed advocate of a puritanical ideology. Have we even debated on the increased use of mob justice from cases of alleged blasphemy cases to the lynching of young men declared guilty without trial in Sialkot in 2010, and to instances of petty theft on streets. Injustice and inequities fuel this fire and those at the helm remain busy in pursuing the most trivial power games, played time and again in the sordid political history of Pakistan.

Many have asked for arrests, others have demanded suo-motu notice to push Farzana’s case. The few dozen civil society activists are busy chanting the decades-old slogans. All of this has been tried with no results. Mukhtaran Mai could not get complete justice despite the suo motu, the highest level of judicial intervention. And in the presence of discriminatory laws, how will victims of honour crimes even think of justice?

There is something even more troubling at work. And it has to with the abdication of state responsibility. It is simply a breakdown of the fragile postcolonial citizen-state relationship. Whether Pakistan’s moth-eaten political parties and its truncated democratic process have the capacity to re-craft that relationship is unclear. Thus far, the signs are not encouraging.