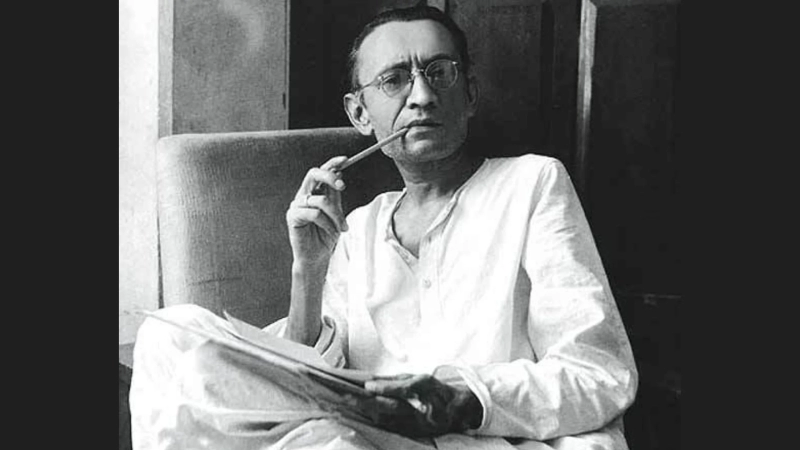

“Here lies Saadat Hasan Manto and with him lie buried all the secrets and mysteries of the art of story writing. Under mounds of earth he lies, still wondering who among the two is the greater story writer – God or he.” (Manto’s self-composed epitaph)

The decision of Pakistan’s civilian government to accord the highest civilian honor to Saadat Hasan Manto comes as a minor, though significant, attempt at our national course correction. It took fifty seven years and a light year of denial for the state to recognize the worth of our great writer and commentator. Even though Manto dreaded the idea of a posthumous award, the conferment of a top state honour is a debt that Pakistan’s anti-intellectual and repressive state owed to the genius of our times.

Saadat Hassan Manto was born on 11 May 1912 in united Punjab’s Ludhiana district. In a literary, journalistic, radio scripting and film-writing career spread over two decades, he produced at least 250 stories, scores of plays and a large number of essays. He also worked with the All India Radio. Perhaps the best years of his life were spent in Bombay where he became associated with leading film studios. Manto also wrote a dozen films, including Eight Days, Chal Chal re Naujawan and Mirza Ghalib. The last one was produced into a movie after he moved to Pakistan in January 1948.

After 1947, Manto was shoddily treated by the new state of Pakistan. This towering writer had become a sensation even before his migration to Pakistan. Manto’s scathing irony and the proclivity to subvert conventional wisdom was already well recognized. But it was the senseless and horrific violence of the partition which gave a new dimension to his writings, and made him both into a story-teller par excellence and a social historian of immense depth and variety.

In Pakistan Manto was tried for ‘obscenity’ and the right wing launched a full-fledged campaign against him. It is a bitter irony of our confused society that in 2012, Pakistan’s Supreme Court has entertained petitions from an Islamic party representative and a former judge against television channels airing Indian programmes and thereby spreading ‘fahashi’. Manto’s chilling story “Thanda Gosht” – a no-holds-barred indictment of violation of woman’s body and desecration of humanity invoked the ire of puritans. It is a separate matter that the story has gained global traction and acclaim.

As Ayesha Jalal says Manto was ‘vulgar’ because what he saw in his surroundings was vulgar to him. It was the environment that caused him to attain that degree of directness in his writings. Manto was faced with over half a dozen charges of obscenity, three of which occurred before Partition and three after he moved to Pakistan. Even out of these, the court found only two stories in which he had transgressed the law and was liable to punishment. It would be unjust to call a writer’s work obscene just on the basis of two stories. But then we are good at defying logic.

Manto has complained in his inimitable style how he struggled to find a niche in Pakistan:

“You the reader know me as a story writer and the courts of this country know me as a pornographer. The government sometimes calls me a communist, at other times a great writer. Most of the time, I am denied all means of livelihood, only to be offered opportunities of gainful work on other occasions. I have been called an expendable appendage to society and accordingly expelled. And sometimes I am told that my name has been placed on the state-approved list. As in the past, so today, I have tried to understand what I am. I want to know what my place in this country that is called the largest Islamic state in the world is. What use am I here? You many call it my imagination, but the bitter truth is that so far I have failed to find a place for myself in this country called Pakistan which I greatly love. That is why I am always restless. That’s why sometimes I am to be found in a lunatic asylum, other times in a hospital. I have yet to find a niche in Pakistan.”

The experiential trauma of partition and the incredible violation of humanity that took place during the 1947 riots took everyone by surprise and to date historians, sociologists and psychologists remain busy analyzing what was happening in the communities, which had been fairly peaceful and integrated for centuries. Each year we find new studies offering fresh and not-so-fresh perspectives on partition violence. Citing Manto has become almost mandatory for any writer who endeavors to explore the tragedies of 1947. This is why Manto’s short story Toba Tek Singh remains perhaps the most nuanced account that rises above and the same time defies the communitarian and nationalistic interpretations of history. Much has been said about this story, but its placement of humanity in a no man’s land remains unmatched in its intensity, satire and poignancy.

Partition remained a mystery to Manto who could not fathom why members of different religious communities could not peacefully coexist in the subcontinent. His helplessness and confusion acquired a powerful expression in his writings:

“…my mind could not resolve the question: What country did we belong to now – India or Pakistan? And whose blood was being so mercilessly shed every day? And what about the bones of the dead, stripped of the flesh of religion, were they being buried or burnt? Now that we were free, who were our subjects? When we were not free, we used to dream of freedom. Now that freedom had come, how were we to view our present state? Were we really even free? There were different answers: the Indian answer, the Pakistani answer, the British answer, Every question had an answer, but when you tried to unravel them to get to the truth, you were left groping.”

Through his literary works, Manto envisaged a subcontinent free of differences due to religion, caste or creed. Sixty-five years on as India and Pakistan celebrate their respective “Independence” days, Manto’s artistic vision remains brutalized.

Manto did not live long to see what became of Pakistan. Had he been alive, he would surely have landed in a mental asylum for long. Pakistan’s persecution of its minorities, the gradual shifts towards a manufactured Islamic identity and the blatant use of religion for political power would have tormented Manto.

Writers and artists in Pakistan who are forced to crop and censor their works must always keep Manto’s example before them who did not surrender his freedoms. Ultimately, the state has had to acknowledge the majesty and mastery of his writings.

At least there was something to celebrate on this Independence day.

Translations of Manto’s works used here were done by Khalid Hasan

August 17-23, 2012 – Vol. XXIV, No. 27