Komail Aijazuddin’s artwork marks a step beyond the earlier explorations of the baroque symbolism

Komail Aijazuddin is a representative of Pakistan’s younger generation of artists that is renegotiating the possibilities of artistic expression. In a sense, the works of Komail and many others have helped to create a new aesthetic that draws from the tradition but reinterprets and subverts it with much flair.

Komail does not belong to a traditional school or the cabals created across the country that usually sets the styles of art practices in the country. Trained in New York (at New York University and the Pratt Institute), Komail Aijazuddin brings the Western traditions into his artistic experience and fuses them with the Pakistani traditions of religious symbolism and devotional narratives.

76.2 x 56.3 cm

mixed

In Saint in Silver, the division between the sacred and the common is a border

In his early works, Komail ventured into a forbidden arena of imagining the range of figurative within the Islamic traditions. Thus the Shia and the Catholic motifs found echo, and continues to speak, in the growing corpus of work. He did not stop there but added other traditions into his oeuvre, such as Buddhism, which were once native to regions comprising Pakistan. Given the nature of contestations and violence that surrounds religion in Pakistan, Komail’s work goes beyond the formalism of the motif and has been turning overtly political. The intersections of personal faith and the cultural milieu littered with the notions of blasphemy, purity and public religiosity have defined the various and prolific phases of his art practice.

Grace in hand a new series of work currently on display at Khaas Gallery, Islamabad, mark a step beyond the earlier explorations of the baroque symbolism and turn more inward using almost a miniature format. However, the style on display has nothing to do with the done-to-death miniature painting of 1990s and beyond. This series is quite postmodern in its range as is reinvents and deconstructs the well known tradition of illuminated manuscripts.

76.2 x 56.3 cm

mixed media on paper

2015

The transnational modernism of Pakistani art, popular until the 1990s, was replaced with bolder experiments. In particular, the two trends have been dominant in the words of Iftikhar Dadi, an art historian at Cornell University the interrogation of tradition and the exploration of popular culture, since then.

Komail’s new series is also reflective of these currents but employs an original vocabulary. Grace in hand uses the techniques of illuminated manuscripts (distinct for its devotional texts) and by using the primary means of drawings collates multi-layered stories. The drawings of this series are interwoven almost as a single entity like a book or codex.

Books in the medieval era were illuminated with gold or silver, bright colors, intricate designs that supplemented and created a parallel narrative to the text. Both European and Muslim societies produced a wide range of texts of this genre. The reader of the text through the use of colours would feel that the page had actually been illuminated. Here the border of the page was also meaningful for it often had drawings or written text adding yet another layer to the script. The use of imagery had an important function: of making the ideas accessible for other cultures. The dual purpose of narration and transmission therefore is at the heart of an illuminated manuscript.

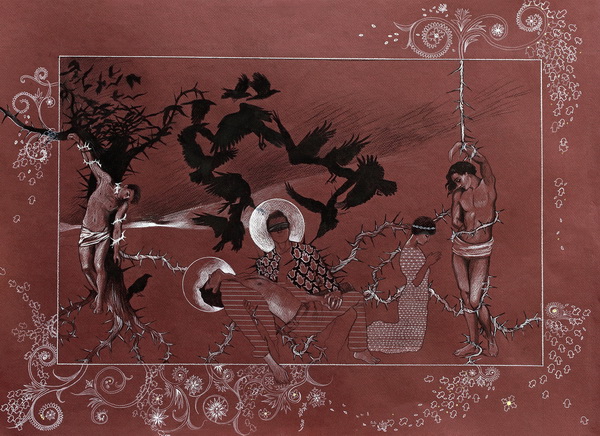

Komail’s drawings play with this tradition and explore the border as imaginary spaces. But these borders were not always linear or sacred. Despite the sacredness of text in many of the older scripts, the boundaries have been crossed, broken or violated. As the artist in his statement mentions this idea one of the creation and disruption of boundaries influenced Hand in grace.

These drawings are also informed by the patterns found in various French and Spanish (11th – 13th century) Romanesque manuscripts, as well as from the Persian texts of the same era. In some of the works the border is depicted without a marked line and in others the halo again a tradition is also imprinted in multiple ways.

76.2 x 56.3 cm

mixed media on paper

2015

All work is autobiographical to some degree

For instance, in Saint in Silver, the division between the sacred and the common is a border. In other works of this series such as Birds of Paradise (I and II), the artist dispenses with the rectilinear form altogether and the border is suggested with elaborate halos and bases, rather than lines. Here are drawings where thorns burst into hands, an unrealized acknowledgement that the line in these drawings is often a stand in for the divide between the human and divine.

Composition with Border was the first drawing the artist created as he started the work on this series. As the only horizontal piece, it also introduced a variety of motifs that are used in the subsequent drawings. It is an intense work that depicts the search for a new vocabulary and visual language by the artist. Other drawings are less busy with a conscious choice to show negative space as a symbol itself.

76.2 x 56.3 cm

mixed media on paper

2015

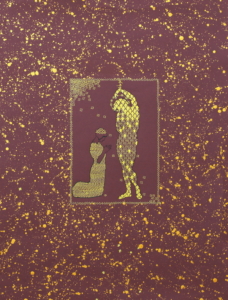

Hands, thorns, impressions of the Pieta recur in the various works. The hand has been a consistent element of Komail’s visual vocabulary. The hands exist in the drawings in essence like a God particle i.e. a symbol of the divine. The Hamsa, or the Humes hand, the Hand of Fatima and the Hand of Miriam is a common symbol in the Middle East and northern Africa both in Islamic and Jewish faiths. In Shia faith, it also represents Hazrat Fatima (RA)’s protective blessings and a marker of her struggle for the truth. These drawings use the symbol adroitly and interpret in a universal manner.

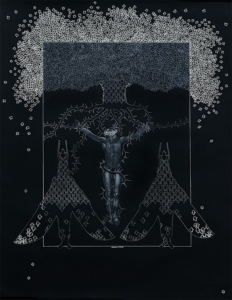

For instance, the drawing Composition in Gold 1 has a grid in the figure, and the idea of the cascading golden hands falling down the inside of the silhouette represent ethereal ideas, perhaps a suggestion of Faith or divinity.

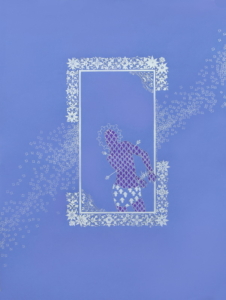

The image that struck me was Green Ascension where Komail has uses the colour green almost that of the Pakistani flag, along with a crescent, and with a figure in ascension. This work turns into a metaphor of hope, liberation and attachment. In fact, it remains one of the joyous works of this series.

76.2 x 56.3 cm

mixed media on paper

2015

Another work of this series Enthroned with Halo highlights a Christ-like figure literally enthroned and surrounded by creeping thorns. The thorn is another symbol that runs through the drawings and as Komail tells me due to both personal affinity and also because of its art historical and religious connotations. This work also continues the use of gold splatter that has been part of artist’s earlier work. Komail likes to use gold as allows him to show the fluidity of themes with something as solid and exact as gold.

In a stunning drawing entitled Black Tree, Komail uses the figure of goddess Isis; and shares the lament on the current connotations of this poignant name. The tree in this work gets enmeshed with the hand symbol, which Komail has continued to employ as a impression of the Divine.

Komail’s earlier works were assessed on the traditional canons such as dexterity in drawing. In Grace in hand, Komail has answered some of the critics and turned the box upside down before leaving it. This series is a reminder of Komail’s continuing journey as well as the boldness that defines the Pakistani artists refusal to bowdlerize their creative expression despite the gargantuan odds.

Interview with Komail Aijazuddin

RR: Your new works make a departure from the earlier styles. What has been the inspiration?

KA: The new work came out of my effort to engage with the idea of illuminated manuscripts. Drawing has always been a big part of my practice and as the work progressed it began creeping into my canvasses. I’ve always considered many of my works on canvas to be essentially drawings, though they’ve been received as paintings. But I hadn’t really worked with paper very much and was interested in seeing what would come out of it. Conceptually the work grew quite organically from themes I was already interested in: divinity, loss, statehood, faith, ascension, progression, iconography etc,.

RR: Throughout the series, you play with borders. Are you reinventing them?

KA: I’m not sure I’m reinventing them, but I did rely on them as a departure point. A blank page can be a daunting prospect and there is finality to the mark making that requires you be very sure of what you put down. Also drawing can be quite a liberating and spontaneous medium. I knew I was thinking a lot about illuminated manuscripts and visually they always relied on a divide between text and image, of picture and frame. The violation of that frame, like when a hand or cloud wanders past the line of the picture plane, was always the most interesting part of the pictures for me (this is true of miniatures and Romanesque manuscripts both). The break seemed incongruous and insightful, like I’d stumbled onto a secret by mistake; in violating the pictures internal logic, the viewer is made aware that the logic exists in the first place. I think its all rather meta.

RR: Was there a conscious choice to investigate borders?

KA: I began playing around with the idea in the beginning. I’d set up a few rules (like a rectangle, or a tree) and then just keep adding elements as I went along, almost like a little game. I rarely planned the images from the onset and the border allowed me to have a structure around which I could playfully improvise. Some borders were simple lines, others were ornate motifs taken from Persian brocades or 13th century illumination or building decorations.

RR: The figures in these series represent movement but there is resignation of sorts? A sense of loss? Who are they?

KA: I’m not sure who they are but I guess that they are all of us or at the very least part of me. When I began the drawings I was still articulating the figures,-drawing their facial features, the light and shadows, the musculature. Some were lifted straight from local art history, others from movies, some from my previous work. But the more I thought about it, the less it mattered whether or not you could make out their faces. Using just the outlines of the figures allowed me to use the idea of human form without being bound by them. So I began using silhouettes and filling them in with 2D patterns of the hand of Fatima.

Religious art, indeed religion itself is usually about life after death so yes, loss is a big theme in my work but it’s not something I consciously think about anymore. Actually I think of many of the figures (like the ascension figures) as quite triumphant, more about overcoming obstacles than succumbing to the agony of them.

RR: Is there an autobiographical element in some of the drawings and more importantly the figures?

KA: I suppose all work is autobiographical to some degree. The one thing I set out to do with this body of work was to remove any sense of the narrative from the images. I didn’t want there to be a particular story in mind nor any real connection to realistic picture. The line of the silhouette allowed me to imply form without necessarily making it. When I considered the drawings as a whole it struck me that they are, basically, the articulation of dozens of little thoughts loosely interconnected. But these connections are more about the formal concerns of mark making and drawing than they are about portraying a particular concept or event from my life. That’s not to say that they don’t have intentional content, but rather that that content is more opaque and, hopefully, universal.

RR: And the male figures?

KA: The male figures appear usually in references to either Christ forms, or St Sebastian and in some cases a reimagining of the pieta. I’m not sure why they began appearing to be honest. Maybe its because we in Pakistan find the male form less offensive than the female figures, and I wanted to figure out why.

RR: This series has another notable departure from your earlier works i.e. the Wax Formation and the layers used as a medium. Why did you choose this mix of techniques?

KA: My interest in deconstructing the power of the border led to the idea of deconstructing the paper (and image) itself. This led to the Wax Formations. Each Formation is made up of several different drawings on translucent paper, which are then pressed together to create one image. I would often start with letting chance dictate how ink or paint would form an abstracted shape, unencumbered by intention. Using whatever resulted as a base, I would then create another layer, and another and another, often not establishing a relationship between them until nearer the end of the process. I wouldn’t know what the final image would look like, and this released me from any loyalty to a narrative without forgoing content. These drawings vary in concept from ruminations on text (to me yet another manifestation of art on paper) to contemporary coding, Eastern miniatures and printmaking.

It was exciting for me because it allowed the element of chance to enter my work, which terrified me and therefore seemed like a good idea. In my experience it’s never productive to get too comfortable in one way of working.