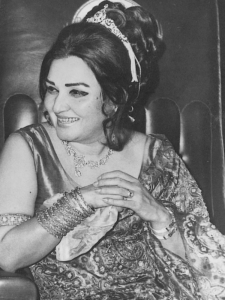

The twentieth-century trajectory of Pakistani music and stardom are epitomised in the life and works of Madam Nur Jehan (1929 – 2000) also known as Malika-e-Tarranum. Had there been no partition of boundaries, musicians and composers in 1947, she would have been a subcontinental diva. A common Punjabi aphorism, loosely translated, states that there never was and never will be anyone like Nur Jehan. With her incredible talent, fiercely independent persona, flamboyance and ingrained humility, she surpasses even the best of global icons. The complexity of her life and times have yet to be appreciated: breaking with convention, she defined a new set of rules in the male-dominated entertainment industry, manipulating it where possible to ensure that she would not become the archetypal exploited South Asian singer. Her wit and lust for life remained till the end, and with the exception of not having died in her beloved Lahore, she died with no regrets.

When nine years ago, the Queen of Melody breathed her last breath in a Karachi hospital, the circumstances of her death were considered peculiar by the believers. Even in death, she achieved what ritualistic Muslims seek all their lives – to die on the holiest day of the year. The twenty-seventh night of the holy month of fasting is widely believed as a night when all prayers are answered and the gates of forgiveness are opened. This is reportedly the reason that her Karachi-based daughters hastened her burial. (Other less spiritual accounts explain it as a consequence of conflict among her children by different husbands, and the struggle to control family assets).

The epic musical journey of Allah Wasai (Nur Jehan’s given name) began from Kasur and encompassed the various shades of early twentieth-century cosmopolitanism in undivided India. Born into a family of small-time performers, her talent got recognised when she was barely six years old: as a child she bore the uncanny gift of being able to render a folk piece and a popular theatrical number with effortless ease. When her family moved to Calcutta – a haven for all of India’s indigenous talent – in the mid-thirties, Mukhtar Begum, an established singer, encouraged the young girl from Kasur to hone her gifts. Mukhtar Bai recommended the family to her partner, Agha Hashar Kashmiri, manager and owner of Maidan Theatre. It was here that Wasai received the stage name Baby Nur Jehan. During these four years, a child star was born. Cast in several films, she attained exposure to the innards of a popular culture dominated by cinema at a very early, impressionable age.

Back in Lahore, Nur Jehan was presented to Master Ghulam Haider who trained her in the intricacies of formal singing and composed some of the early songs that made her immensely famous. Her remarkable talents were soon noticed, and Nur Jehan was cast as a heroine in Khandan (1942) opposite Pran, the first film by budding director Shaukat Hussain Rizvi, who later became Madam’s first husband. An uninterrupted series of successful pictures, together with the lilting melodies which established Nur Jehan’s career, made her virtually invincible. By 1947 she had several hit films under her belt: Nadan (1943), Naukar (1943), Dost (1944), Lal Haveli (1944), Mirza Sahiban (1947) and Jugnu (1947). The latter’s male lead, Dilip Kumar, was to become a heartthrob for decades (1947) and a friend of Nur Jehan for a long time to come.

The year 1947 was, of course, a watershed for an entire generation. Nur Jehan was among those who adopted Pakistan as her country and by the late 1940s, began a new phase of her career. It was no less dazzling than her all-India glories, as hugely popular flicks such as Dupatta, Intezaar, Anarkali and Koel testify. This was also the period of Madam’s collaboration with another giant composer, Khawaja Khursheed Anwar. This immortal partnership resulted in the production of music that defies all definitions: neither pure filmi, nor classical, nor indeed folksy in any exclusive sense, the songs of this era surely remain a highpoint in the history of Pakistani music. Nur Jehan related years later in an interview with Khawaja Khurshid that she alone could sing “Sagar roay laehrain shor machayain, yaad pia ki aye” (The ocean weeps and the waves scream as I think of the beloved). Even Nur Jehan found this a challenge given that the base of this song entailed a difficult raga (mian ki todi) and the high pitch, which would have been beyond even many a formidable voice. The similarly difficult Dil Ka Diya Jalaya (lighting the lamp of my heart), rendered in Rag Darbari, would surely have made Tansen proud had he lived to see the ultimate embodiment of his genius in the public sphere. In 1957, the Pakistani state awarded her the President’s Award for exceptional acting and singing.

Nur Jehan’s film career in Pakistan climaxed with the release of Mirza Ghalib (1961) which established her firmly as an icon. Around the same time, she immortalized Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s “Mujshe pehli si mohabbat mere mehboob na maang” with an extraordinary soul-stirring rendition. Faiz the poet was also stunned by the performance and is reported to have gifted the poem to Madam as a tribute to her golden voice.

In 1963, the Queen of Melody retired from her acting career after a 33-year association with the silver screen. By now she was married to Ejaz Durrani, a younger lead actor, and was a mother of six. The marriage with Ejaz was never going to last: no ordinary woman, Nur Jehan guarded her independence fiercely and her self-esteem was paramount. Ejaz was drawn to another Punjabi film heroine Firdaus. The inimitable Madam reportedly refused to undertake playback singing for Firdaus and this was the end of the latter’s otherwise resounding career as a buxom-bravo Punjabi jatti. Sweet is the taste of revenge.

Perhaps the greatest of moments in Nur Jehan’s long career was the 1965 Indo-Pakistan war, when she fearlessly reached Lahore’s radio station despite the curfew and bombings. Her patriotic songs are unique for their eclectic range: from the Punjabi folk and semi-classical “Aye Puttar hatan te naee wikday” to the complex composition of “Aye watan ke sajeelay jawano”, they boosted the morale of the entire nation, not just the soldiers of Pakistan army. Such is their magic and force of spirit that to this day, they are played during military exercises. As a performer, Madam was at her best: draped in somber saris, her expression and body language brought together the feminine and the masculine, mixing fear with hope; anticipation of victory with a deep-seated quest for the glory of the struggling nation-state. Many say that it was she, rather than the generals, that the Pakistani public was most inspired by. The state was quick to respond to this momentous role and awarded her Tamgha-e-Imtiaz (The Pride of Performance), Pakistan’s premier civil award, in 1966.

In the 1970s, Madam had reinvented herself, responding to new trends that required faster tracks. However, her increased focus on the Punjabi film market irked many as they saw her boundless talent being diluted. But commercialisation of film music was a reality and Nur Jehan confronted it with her usual bravado. Raunchy numbers such as “Meri vail di qameez logo pat gayee aye” and “Kithay jan ge charray dil walay” were sung with the same zest and pleasure with which she sang ghazals.

Only a unique talent such as Madam’s could successfully handle this apparent contradiction. Her patriotism notwithstanding, all through these decades, she personified the basis of India and Pakistan’s shared cultural heritage. When she visited India in 1982 to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Indian talkies, she was received in a style grander than heads of states receive. The Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, Dilip Kumar and Lata Mangeshkar hosted her like a long-lost relative. The legendary music director Naushad Ali is reported to have said that Nur Jehan was a better singer than the Indian music industry’s “queen empress” Lata Mangeshkar. Lata always called her Didi and graciously acknowledged Madam’s stature. The two divas remained close friends throughout the lifetime of Nur Jehan.

Her life also inspired the leading Urdu writer Manto to write a biographical sketch, “Nur Jehan, Surooray Jehan”, which highlighted the extraordinary creativity of her singing and her eccentricities. Enamoured by the enormity of her talents, Manto could not resist his characteristic brutal approach by pointing out her ambitiousness, evident in the way she ousted another upcoming actor-singer Abida Sultana. Other critics pointed to the way Runa Laila was treated in the late 1960s: it is alleged that Madam was not all that kind to her junior when she emerged as a formidable rival in the popular domain.

Despite the failed marriages and unsatisfying relationships, Nur Jehan had a full family life. As an involved, mercurial and passionate mother of six children, she found her anchor in simple domesticity where she would cook, feed her children and spend hours with the grandchildren. Her philanthropic contributions had already acquired a legendary status in her lifetime. From her poor relatives in Kasur to the underclass at the recording studios, she was generous with her money. It is said that she would spend a good amount of her cash after each recording spree at the Lahore studios. Such was her reputation that the gates of her house on the main boulevard in Lahore’s up-market Gulberg area were almost always crowded by the needy. Most did not leave the site ungratified. Today, the road leading to Liberty Market, opposite her house, is appropriately known as Nur Jehan Avenue.

There was virtually no one in Pakistan who did not react to her music. Millions of admirers, envious peers and juniors all had something to say about her. Shortly before her death, the minor singer Tahira Syed created a little stir in the local press when she denigrated her voice and placed Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan above her. There was a storm led by Madam’s students and fans and the incident soon turned ugly, as often happens in the “land of the pure”, with threats hurled at the hapless Syed and press statements issued in her favour.

Admirers of the Melody Queen also included rulers. In almost every phase of Pakistan’s power-obsessed history, the top man (and in the case of late Benazir Bhutto, top-woman) had to bow before Nur Jehan’s stature. The infamous General Yahya Khan was obsessed with her. Bhutto held her in high esteem and even General Musharraf visited the ailing diva in Karachi right after capturing power in 1999. On Rajiv Gandhi’s successful visit to Pakistan in 1989, for which Benazir Bhutto had to suffer for nearly a decade on account of her “softness”, Nur Jehan was specially flown into Islamabad. Gandhi met her with tremendous respect and Madam stole the show at the cultural soiree organized at the jinxed Prime Minister’s House. Earlier, in the 1970s, a provincial High Court Chief Justice was smitten by her and reportedly wanted to marry her, but frustrated by a torrent of middle-class conservatism. It is unclear how seriously Madam took these advances, though her occasional tendency to mock them suggests something of a feminist spirit ahead of its times.

And yet, eight years after her death, there is not even a single complete biography of Nur Jehan. Had it not been for Khalid Hasan’s biographical sketch, we would have no written record of her life and times other than the saucy tales written by yellow journalists. The state and its multiple cultural institutions strangulated by bureaucratic pettiness and conspiracies have not even bothered to collect and document her vast musical legacy. Last year, I was dejected to note that most music stores did not sell “Abhee dhoond hi rahee thee tumhay yeh nazar hamaree” (though subsequently heartened to learn that Youtube has facilitated the recovery of her repertoire through new media tools).

My fear is not just that Nur Jehan will be forgotten. Virtually all Punjabi singers ape her shamelessly and almost any wannabe singer in Pakistan has to perfect a few numbers of hers before venturing on a solo career. The real concern is that by hiding her life from younger generations and reducing the corpus of publicly available music, we are denuding society of its most veritable post-Independence cultural heritage.

Who’s afraid of the unconventional and ferociously independent life of Nur Jehan?

The answer is not difficult to guess. Conformism of the socio-religious variety, kitsch commercialism and middle-class morality are all embedded in the institutions of a society that finds itself unable to celebrate a life so uniquely individualistic and yet so dear to the public imagination. With Nur Jehan’s demise, silence replaced music. The subcontinent lost one of its finest voices.

By remembering Nur Jehan this December we are holding up a mirror to our not-so-distant past – a rich treasure of melody we seem strangely eager to erase. True to her record, the Queen of Melody will defy this as well.

Gaye gee duniya geet meray

sureelay ung mein niralay rang mein

bharay hain armaano mein

One is almost certain of that.