In the West, experts on Iran can be divided into two broad categories: academics/scholars and journalists. Nikki Keddie (academic) and Robin Wright (journalist) in the United States, Giles Kepel and Olivier Roy (both research scholars) in France, and Fred Halliday (academic) and Dilip Hiro (journalist) in London are the most prominent and highly regarded specialists on Iran.

After Keddie, Hiro is the most prolific writer on the subject – his recent book The Iranian Labyrinth: Journeys through Theocratic Iran and its Furies being the fifth on Iran, 14th on Middle East history (including a popular trilogy on Iraq after 9/11), and 28th (five fiction and 23 non-fiction) overall.

Born in Larkana before partition, Hiro was educated in New Delhi and the United States, before settling down as a journalist in Britain in the mid-1960s. Two of his previous books on Iran, Iran Under the Ayatollahs and The Longest War: The Iran-Iraq Military Conflict, were widely read – the latter regarded as the definitive history of an under-reported war. Drawing heavily on his previous works, Hiro’s The Iranian Labyrinth is an important contribution to informed and dispassionate analysis on Iran, something in short supply in today’s politically polarised and emotionally charged environment.

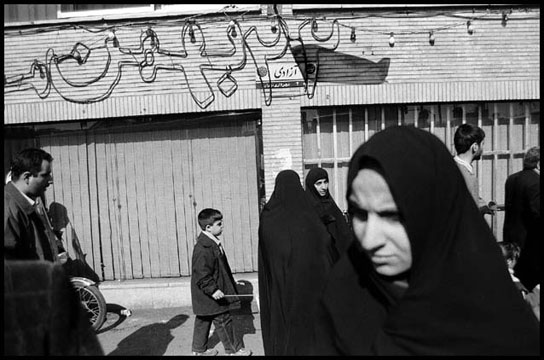

Divided into 10 chapters, this concise book, a mixture of ‘travelogue, history, and socio-political analysis’, covers the essential episodes in Iran’s turbulent and tumultuous history since early 1900s. (The book was published last year before President Ahmednijad’s surprise election). A frequent traveller to Iran, Hiro navigates the labyrinth: hijab-wearing women are the majority at the universities, Iranian films win prizes at international festivals, and human rights lawyer Shirin Ebadi is a Nobel peace laureate, a rising number of intellectuals, women, youth and journalists protest the socio-political restrictions imposed by the Islamic regime.

Divided into 10 chapters, this concise book, a mixture of ‘travelogue, history, and socio-political analysis’, covers the essential episodes in Iran’s turbulent and tumultuous history since early 1900s. (The book was published last year before President Ahmednijad’s surprise election). A frequent traveller to Iran, Hiro navigates the labyrinth: hijab-wearing women are the majority at the universities, Iranian films win prizes at international festivals, and human rights lawyer Shirin Ebadi is a Nobel peace laureate, a rising number of intellectuals, women, youth and journalists protest the socio-political restrictions imposed by the Islamic regime.

Iran, Hiro asserts, is probably the most strategically important country in the world, with a uniquely distinctive history. It was the first country in the Middle East to find oil in commercial quantities; to experience a constitutional revolution (1905-11) resulting in the first parliament (called Majlis) in the region in 1907; to evolve into a constitutional monarchy with a multiparty system in 1941 – till 1953 when a coup masterminded by the CIA of US re-imposed royal dictatorship; to challenge Western economic imperialism (well before Nasser’s nationalization of Suez) by nationalizing Anglo-Iranian Oil Company in 1951; to become a victim of CIA’s machinations against a legitimate democratic government (headed by charismatic and nationalist prime minister Mossadegh) in 1953; and to experience a genuine revolution, in which millions participated, but which was primarily inspired by religion and spearheaded by religious figures, an unprecedented phenomenon in modern history.

The United States, for the first time, developed a taste for ‘regime change’ in 1953: Far from spreading the gospel of democracy, CIA orchestrated a coup against Iran’s most popular, secular and democratically-elected prime minister Mossadegh and brought back the Shah – a corrupt, inept, and autocratic megalomaniac – to the Peacock Throne.

In return, the Shah leased the rights and management of Iranian oil, for the next 25 years, to Western oil giants, who exported 24 billion barrels of oil during the next 20 years for just $1.80 per barrel. (At the time of Shah’s departure, oil prices spiked up to $31 per barrel). The most successful/lucrative operation in its history, CIA developed it into a “template for overthrowing progressive, nationalist regimes throughout the Third Word”.

Iranians termed it as the “biggest heist in history” and later regarded President Carter’s electoral defeat in 1980, due to the Iran hostage crisis, as an instance of ‘poetic justice’ – Ayatollah Khomeini became the first foreign leader to determine a US presidential election outcome.

Iran’s landmark Islamic revolution in 1979, post-revolutionary xenophobia, and anti-imperialism are all firmly rooted in its historical experience during the last century. Other important factors that determined the course of the revolution and its post-revolutionary behavior include the critical nexus between bazaar merchants and clergy, economics of oil, the peculiar characteristics of Shia Islam (special emphasis on opposition to tyranny), and the cardinal role of Ayatollahs/senior clerics in Shia Islam.

Senior clerics (Mujtahids/Ayatollahs or Grand Ayatollahs) in the Shia world have always commanded the reverence of their followers for three primary reasons: superior religious knowledge based on a strong tradition of ijtihad, personal piety and moral leadership. From 1964-1979, Ayatollah Khomeini, in exile, assumed the leading role and mobilised the masses against the Shah, from abroad, through the network of mosques and seminaries and coupled with the active participation of intellectuals, merchants, and students.

Recently this phenomenon of extreme influence exercised by a senior Shia cleric has been demonstrated in Iraq, where Grand Ayatollah Ali Al Sistani, an Iranian national who speaks Arabic with a Persian accent and is ineligible to vote in Iraq’s elections, is the most important man determining the destiny of that nation.

Hiro’s knowledge of Iran’s political system is very impressive. Contrary to the prevalent view in the West of an authoritarian regime in Tehran, the Iranian constitution has more checks and balances than many of its Western counterparts.

He discusses the five primary centres of power (leader, president, Majlis, assembly of experts, and judiciary) and two secondary ones (Council of Guardians and Expediency Council) and asserts that Iran, given the multiple centres of power, resembles more the United States than China.

The opponents of Iran’s Islamic democracy find Islam and democracy incompatible and argue that the present system is authoritarian and beyond redemption. Proponents believe that the conservative-reformist struggle is the dynamic of Islamic democracy, the first attempt of its kind, which can serve as a working model (left-right political divide or two party system) for the rest of the Muslim world.

In 1991, Graham Fuller, an American scholar at the prestigious RAND and author of The Future of Political Islam, titled his book on Iran as Centre of the Universe (translation of one of Shah’s many titles!).

Given the current brinkmanship and standoff over its nuclear program, Iran is likely to be the centre of the world’s attention, if not the universe, at least for the next few years. Hiro’s informative and illuminating book is a must read for all those who want to understand this important, unique, and complex country.

First Published in Daily Times in February 2006

Read more related articles:

Hassan Rouhani: Iran’s New President Will Build Alliances With India and Afghanistan