Raza Rumi reviews a book on the life and works of Akhter Hameed Khan, a legendary development guru

“It is not enough to say that he was a great man. He was one of the great human beings of the past century. He was so much ahead of everybody else that he was seen more as a ‘misfit’ than appreciated for his greatness…” (Nobel laureate Dr. Younas Khan on Akhter Hameed Khan)

In a country where idealism has taken a backseat and opportunism and greed are rampant, this book about the life and works of Akhter Hameed Khan (AHK) can be read as a kind of counter-narrative, a perennial challenge to Pakistan’s always-imminent descent into chaos. The AKH Resource Centre has done a fabulous job in putting the various trends of his thought and action into this lean volume, which is remarkable for its authentic voice and utter credibility.

Eighteen years ago I had the rare opportunity of working at the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) under the leadership of Khan Saheb’s best known disciple, Mr. Shoab Sultan Khan. (AKRSP came years after experiments in community development and self-help programs such as Commila and the Orangi Pilot Project.) I was lucky enough here to meet the great AHK, if only briefly.

AHK, as he comes across in this book, was a curious mix of the Sufi visionary, the man of Gandhian principles, the subaltern researcher and a dedicated community worker. With his hybridized eclectic thought, in particular his approach to poverty and the poor, Khan Saheb was able to challenge Pakistan’s mainstream development discourse, which to date remains imperial. A colonial and post-colonial state acts as mai baap to its citizens and international agencies are the patrons, defining the problems and opportunities from a knowledge base that is detached from the people it seeks to serve and which, at the end of the day, always reiterates the ascendancy of the Western historical experiences of development, progress and prosperity.

Development failures in Pakistan have therefore been manifold. For example: the IFIs have been forced to admit that two-thirds of their investment in the social sector has failed either totally or partially; or that the Social Action Programme of the 1990s, with 10 billion dollars of investment in it, led to little or no results in health, education and other basic citizen entitlements. If anything, the key indicators have worsened after a decade.

Pakistan’s dilemma of growth-without-development is therefore best explained and addressed by the strategies AHK crafted from his deep connection with the people: Let the people take charge of their lives, as they know best about their needs.

This book is not just another collection of a great man’s sayings. It is a testament to an age gone by – an age that prized humility, tolerance, and the making meaningful of lives. Khan Saheb belonged to the culture of Ganga Jamni tehzeeb, which evolved during a millennium of cultural evolution in India. It was already in decline during the 20th century and the Partition of 1947 completely truncated this process. AHK was a torchbearer of that (now seemingly peculiar) South Asian era: inspired by Buddha’s principles and the lives and teachings of Islamic Sufis who defined the context within which people lived and understood their progress. This is why he was accepted in Comilla with open arms, in the multicultural Orangi, in central Punjab and in Pakistan’s remote Northern Areas.

It should be remembered that Khan Saheb’s experiential wisdom was documented and applied long before the rise of Subaltern Studies, postcolonial claptrap and even the fancy development doctrines that use the term ‘participatory’ like a designer label.

In an essay here called ‘The Comilla Project’, Khan reflects in a rare passage on his moorings (he was not too keen to blow his own trumpet):

“I had been a member of the Indian Civil Service where I learnt the art of imperial administration. Subsequently, I had resigned from imperial service and joined a nationalist institution where I absorbed Gandhian views of morals; a practitioner of what was then the cosmopolitan cult of community development. Besides close familiarity with the imperial, the Gandhian, and the cosmopolitan conception, I had a nodding acquaintance with the Russian and Chinese conceptions.”

AKH is remembered in Bangladesh as perhaps the only positive legacy of the united Pakistan. When I worked in Bangladesh from 2006 to 2008 for an international development agency, everyone talked about him. Ministers, bureaucrats, NGOs, media persons, all would recall his contributions. Khan Saheb’s emphasis on the potential of rural women has been taken forward by Bangladesh with a missionary zeal and the results are clear and tangible. Women are active in economic life, the population growth rates have rationalized and the social indicators are far better now. Comilla faced its share of problems as documented by AHK and later commentators, but large NGOs and the government carried the potential of community development forward. Agriculture extension, cooperative management and local action have changed since the Comilla experiment began.

AHK’s work influenced the work in under-privileged India as well. Kappula Raju’s essay ‘The Gandhian of the Poor’ narrates how in the past 12 years, the poor of Andra Pradesh have transformed their lives by setting up self-managed organizations that cover more than 8 million people. Acquiring the title ‘Gandhian’ is not always easy for Indians and is especially rare for Pakistanis. But Saheb’s stature was and will remain above our narrow limits, in line with his multiple identities.

Perhaps AHK’s greatest legacy in Pakistan is the existence of rural support programmes (RSPs). Khan Saheb’s ideas inspired the operations of these organizations – now 11 in number and covering millions of households from the north to the south of the country. It is also a matter of record that Khan Saheb was not keen on the scale and expansion of the rural support programs. But he also understood the massive need of the populace, given state failures, and entrusted Shoaib Sultan Khan with balancing quality and scale. Today, the RSPs are formidable partners of the government, civil society and the rural poor .

The larger question of the space for creative thinkers and practitioners in Pakistan is an important one. While the region and the world garlanded AHK with honors such as the Magsaysay award, torrents of intolerance hounded Khan Saheb in Pakistan. Fayyaz Baqir’s excellent essay in this book is a key to understanding our present chaos and a valuable document for posterity.

A simple Sufi, a poet and a friend of the poor like Akhter Hameed Khan had to run in the twilight of his life from court to court and even face arbitrary arrests for false charges of blasphemy. This nefarious law inserted by the colonists and then twisted further by General Zia ul Haq’s dictatorship has been a weapon in the hands of the orthodoxy, which has used it unfailingly to persecute the alternative and the innovative. (Lest it be forgotten, Pakistan has also found an apostate in its only Nobel Laureate, Dr. Abdus Salam, who was disowned by the state because of his religious beliefs and was shoddily treated even at the time of his death. We are a really unfortunate country.) In this case an interview with AHK was mangled and carried in the weekly Takbeer in 1988 and, prompted by a disgruntled employee of the OPP, led to the registration of the first blasphemy charge. But the case was filed two years after the publication of the aforementioned interview, and was clearly mala fide in nature. This case proceeded sluggishly. Saheb’s opponents, who were eager to trap him, registered another case against him in 1992 in Karachi for writing an allegedly blasphemous poem for children. (It was interpreted in a regressive way by the usual reactionaries.) Baqir’s essay tells us how Akhter Hameed Khan’s handling of both these cases reflected a Sufi-esque inner unity of his personality. Baqir also tells us how Khan Saheb’s values were rooted in the Islamic concepts of simplicity, charity and social responsibility.

We should resist the temptation now of representing AHK as an Alim and eschew the impulse to add rehmat ullah aleh to yet another great man of our history. Starting with Jinnah and Iqbal, everyone is nowadays given a tasbeeh and an orthodox outfit to go with the so-called ideology of Pakistan. But Baqir has cited primary sources such as AHK’s affidavit, which must be read to get a sense of the progressive, inclusive and modern religion Islam was for some people and still can be.

These blasphemy cases eventually woke up the world, the public conscience and even (at last) the state. The case in Karachi against AHK was withdrawn on the request of the Sindh Government in December 1992. But the judge trying the case turned it down in Punjab, despite the assurance of the Prime Minister. So deep-rooted was (and is) the arrogant prejudice of state officials that even an order of the Prime Minister was disregarded for it.

Renowned writer Intizar Hussain has written how Khan Saheb’s trials and tribulations constituted a ‘bad omen for the poets in Pakistan’. Not just for poets but all creative minds, thinkers and leaders. Pakistan owes an apology to its finest citizen for treating him the way we did.

And yet, as a pucca Sufi, AHK still believed that progress was within reach. I cite a quote from this book: “If you want this country to progress you have to follow examples like Germany and Japan (after World War II). We are still in a better shape because our country is not devastated…How does a community progress? It is taken forward by idealists who want to serve others!”

Khan Saheb’s life and works transcend the realm of ‘development’. They are all-encompassing – relevant for the youth of this country which has been kept away from the fire of idealism; for the thinkers of this country who need to practice intellectual honesty; and most importantly, for the endless array of leaders in the state, NGOs and media, who can learn a lesson or two from AHK’s immensity, austerity and sense of purpose in life.

This book needs to be translated into regional languages and added to the curricula to replace false histories and the prejudice that permeates our lives.

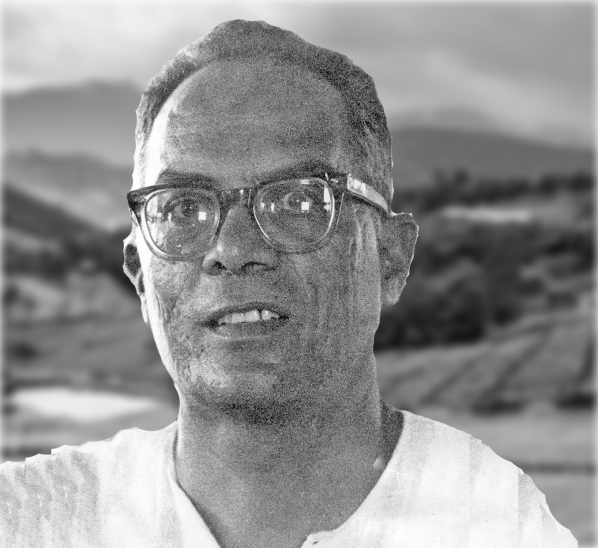

Akhter Hameed Khan (1914-1999)

Akhter Hameed Khan was born in Agra on 15 July 1914. Khan completed his intermediate education in 1930 at Agra College where he studied English literature and history. Later, he attended Meerut College and Agra University and earned a Master of Arts in English Literature in 1934. In 1936, he joined the Indian Civil Service (ICS). The Bengal famine of 1943 and the way the British government handled it disillusioned Khan; and he resigned from the ICS in 1945. After his ICS career, Khan worked as a locksmith for two years to understand the lives of the poor communities. In 1947, he joined Jamia Millia, Delhi, where he taught for three years. Khan migrated to Pakistan in 1950 and within a short while the Government asked him to assume charge as Principal of Comilla Victoria College in East Pakistan, a position he held until 1958. Between 1954 and 1955, Khan worked as director of the Village Agricultural and Industrial Development (V-AID) Programme and was disappointed with the way the communities were supported under this intervention. He attended Michigan State University during 1958-59 for training in rural development. In 1959, he set up the Pakistan Academy for Rural Development (PARDand became its founding director. In the same year, he also started the Comilla Cooperative Pilot Project. For his excellent work in Comilla, he was granted Ramon Magsaysay Award (Philippines) for rural development. In 1964, he was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Law by Michigan State University. Khan remained affiliated with Comilla Project until 1971 and after the creation of Bangladesh he moved to Pakistan. Khan held various teaching assignments in Pakistan before he left for Michigan State University as a visiting professor during 1973-1979. In 1980, Khan moved to Karachi and initiated the Orangi Pilot Project aimed to improve sanitation in the largest squatter settlement in Karachi. He led this project until his death in 1999. Khan also contributed to the development of the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme during the1980s. During his varied career, he authored several books and numerous articles on rural development. His literary works include collection of poems and travelogues in Urdu.

Raza Rumi is a writer, editor and policy expert based in Lahore. He blogs at http://razarumi.com. Email: razarumi@gmail.com