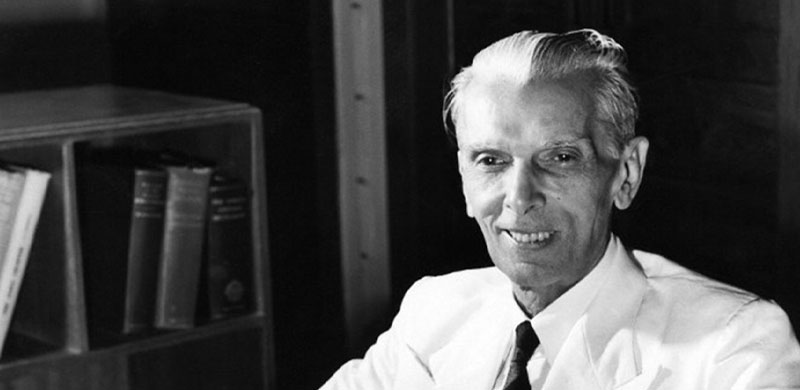

In recent weeks, several commentators have dwelt upon the amorphous notion of Jinnah’s Pakistan, challenging its notional contours and exposing its overt ideological underpinnings. Whilst such a debate is healthy in a democratic society, it becomes a worrying sign in a deeply polarised polity such as Pakistan. Jinnah’s Pakistan was no consensus project: It had several dissenters from the religious right to the Khudai Khidmatgars in the northwest. Perhaps these problematic foundations led to the capture of the state by a national security paradigm, later bolstered by the Islamist discourse.

Blaming Jinnah’s Pakistan as a cause or manifestation of the ideological chaos rooted in our perennial identity question is simply disingenuous. Jinnah may have said different things at different occasions but his views as head of the state are what matter. It was not Jinnah alone who created Pakistan. The politico-economic interests of nascent Muslim bourgeoisie and the famous salariat (to use Hamza Alavi’s term) were the prime causes of Pakistan’s creation. Jinnah nearly gave up the idea of a separate state in 1946 after accepting the Cabinet Mission proposals (the best possible compromise to retain Indian unity). Many critiques of Jinnah overlook the intransigence of the Indian National Congress, documented by HM Seervai. Sadly, both India and Pakistan have buried the fairly objective view of Seervai, as particularistic nation state narratives are always threatened by objectivity.

In spite of the horrors unleashed by Partition, Jinnah insisted on a US-Canada type relationship between India and Pakistan with, open and permeable borders; and even wanted to retire in his beloved city, Bombay. However, he died too early and Gandhi, while fasting for the rights of Pakistanis, was killed by an Hindu extremist (note the absence of this fact in the Indian discourse Hindutva terror started with Gandhi assassination).

India was soon taken over by its political-bureaucratic machinery and Pakistan’s security forces took direct control of power. Such appropriation of Pakistani political space could only work if theIndian threat was amplified to alarming proportions. Consequently, the entire country became a fortress, defending itself from reason, with religion painted on its entrance. Did Jinnah envisage or wish such a polity? No, he warned against it.

Jinnah had a sense of Indian unity above the newly formed states of Pakistan and Hindustan. American scholar William Metz noted in his 1952 doctoral thesis (University of Pennsylvania), that for Jinnah, a Hindu-Muslim settlement was itself a form of Hindu-Muslim unity.

Recounting history is important today. The religious zealots who are silencing voices of tolerance did not believe in Jinnah Pakistan. They wanted a pan-Islamic theocracy what al Qaeda wants Pakistan to become in 2011. Pakistan is a reality but its viability is once again linked to Jinnah’s post-June 1947 vision entailing: a) a secular state, b) resistance to calls for theocracy, and c) a US-Canada model for India-Pakistan relations.

Jinnah’s Pakistan is not dead: Millions of Pakistanis who want a tolerant homeland resent its creeping radicalisation. If not Jinnah, what else do we have to counter the armed extremism on the Pakistani street? If we have drifted too far, which we have, then all the more reason to reclaim the ideal. Denouncing Jinnah’s vision, ironically, reinforces the national security paradigm as well as the Indian nationalist narratives. I hope Pakistani liberals are aware of that.

Published in The Express Tribune, January 21st, 2011.