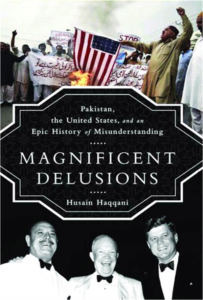

Husain Haqqani’s new book Magnificent Delusions: Pakistan, the United States, and an Epic History of Misunderstanding comes at a critical juncture of Pakistan-US relations as the two nations aim to work together during 2014 to facilitate a transition in Afghanistan. The book offers us a historical view of a deeply troubled yet interdependent relationship and why the year 2014 is likely to be far from smooth. ‘Magnificent Delusions’ has Haqqani’s signature style: Sharply worded, accessible and at times ironical. The book right at the start gives us a flavor of what follows:

The willingness of my countrymen to believe the worst about their ambassador [Haqqani himself] reflects a deeper pathology. Instead of basing international relations on facts, Pakistanis have become accustomed to seeing the world through the prism of an Islamo-nationalist ideology…these self-defeating ideas makes little impact on the rest of the world; the gap is widening between how Pakistanis and the rest of the world view Pakistan.

The first chapter of ‘Magnificent Delusions’ is an eye-opener for it provides the historic basis of a Pakistani worldview. In a tersely worded narrative, the chapter tells us how Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the Quaid-e-Azam in an interview given to Life magazine says: “America needs Pakistan more than Pakistan needs America” and that “Pakistan is the pivot of the world”. The country’s founder thus lays the framework for Pakistan’s foreign policy. Sixty seven years later, Pakistan’s sense of indispensability to the US strategic aims in South-West Asia continues as a delusion that has become a domestic reality. Pakistan’s geostrategic location since Cold War has been vital for West’s policies and perhaps this is why our ruling elites – civil and military – have been able to extract favours and concessions for promises that Haqqani says “..we did not keep”.

The opening chapter shocks the reader a little more as anecdotes tell us of elite behaviour. For instance, the propensity to seek personal favours from the Superpower was there from the very start. From Ayub to Yahya and from Zia to Musharraf our rulers have deemed it appropriate to create a patron-client relationship. To appease public opinion at home they maintain a different narrative. The civilians have been no different. For example, it is widely believed that President Clinton intervened to save Nawaz Sharif from the wrath of military junta in 2000. Maulana Fazl ur Rehman to quote WikiLeaks even asked the Americans to help him become the country’s Prime Minister.

America bashing in Pakistan is also a political weapon. It has been there from the very start as the book tells us. For example in the late 1940s, the Palestine issue was a reason to criticize US by the Indian Muslim leadership that was also concurrently asking for aid and arms for the nascent state of Pakistan. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s troubled relationship dominated public imagination and to date most Pakistanis think that the US had a hand in getting him executed through a mock-judicial process. Similarly, we have a tendency to feel abandoned each time Pakistan becomes less relevant for the Americans. The unrealistic expectations from the US after the Soviet withdrawal also find way in the book. The book is meticulously researched and backs most assertions with sources. There have been voices of criticism that Haqqani has over relied on the American sources but that is a function of accessibility (Pakistan doesn’t declassify documents, US does). In Pakistan, much of the statecraft remains in the ‘classified’ domain. Colonial laws such as the Official Secrets Act, by and large, govern sharing of information. This is why research in Pakistan is not always a pleasant endeavor.

While documenting the ebb and flow of Pak-US relations, Haqqani presents nuanced analyses and never fails to highlight the primary issue that dogs Pakistan’s policymaking ie the skewed civil-military relations. In the book he tells us about his engagement with the military officials. Here is a memorable excerpt:

In an attempt at humor I sent a copy of Samuel Huntington’s book The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations to Kayani along with a four-page summary…But I have no reason to believe that it affected his thinking or decisions in any significant way. Kayani was personally always agreeable with civilians. The Pakistan army, as an institution, still remained a long way from accepting the right of civilians to debate, let alone define, national interest. (page 334)

The book is a bit reticent about his tenure as Pakistan’s Ambassador to the United States. This is where one is a little disappointed but there must be good reasons for this approach. Haqqani is already on the wrong side of military establishment and with him spilling further beans he could be doubly charged.

Historical trajectories aside, the past decade has also witnessed serious ruptures in the transactional relationship masked as a strategic partnership between the two countries. Haqqani writes that two years ago, Asif Ali Zardari, the then President, was sent a letter with an offer of long-term strategic partnership on the condition that Pakistan would fight and sort out the militant groups that were a threat to the region and also the United States. Haqqani narrates how Zardari’s response repeated the ‘strategic’ worldview of Pakistan that predicates on threats from India and Afghanistan. According to Haqqani, Pakistan had “missed the opening for defining its partnership with the world’s sole superpower on more favourable terms than ever before”.

While this may seem like a rational argument, Pakistan has nurtured way too many misgivings about the superpower and opposing America now fits into the definition of national interest. The media, especially vernacular press and noisy TV industry, frequently informs Pakistanis that US wants to denuclearize the country as well as break its Balochistan province. Writing about the period where Haqqani was an actor in the policy circles, he says: “Pasha and the ISI continued to propel ‘hyper nationalist sentiment’ one of the few tools Pakistan had for leveraging itself in an asymmetric relationship”. (page 335)

An unanswered question in the book is why does the US seek Pakistan’s engagement and continues to pander to its elites. Short term interests in the current scenario may give a partial explanation but the long term policy patterns are clear and also emerge from the book. The delusions of Pakistan as well as the Americans can also be found in the book given how both sides think they have leverage over one another and which can be enchased for immediate goals.

Haqqani’s conclusions are somber. In the public domain he has been arguing for a revised framework for bilateral relations that is temperate and cognisant of the stragetic divergences. In the book, he rightly points out that both countries need to be more realistic about their engagement in the future and take note of the fatigue that has set among the peoples of both sides. However, this may not be enough. Pakistan’s progress lies not in the xenophobic tendencies that have been cultivated over years but in an honest engagement with the world that can lead to increased trade, flow of ideas and a less grandiose assessment of its position in the region and the world at large.