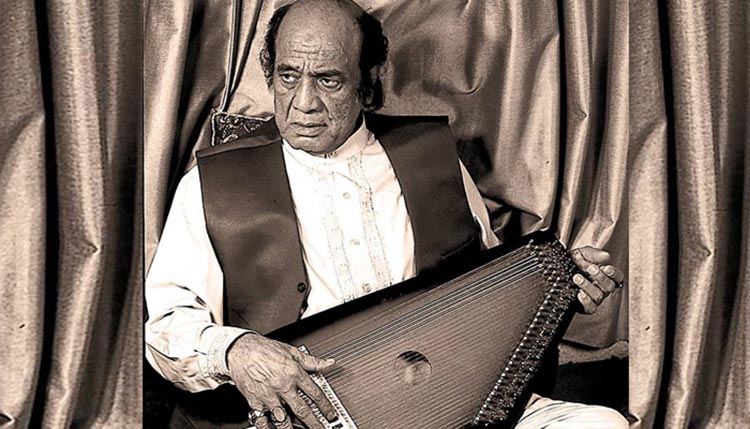

My tribute to Mehdi Hasan published here

He was the musical Midas who transcended borders with the same mastery that he transcended genres

Mehdi Hassan is gone. His devastated fans across the globe will mourn the loss of a voice that ruled their hearts for nearly half a century, a voice in which Lata Mangeshkar said she had found bhagwan.

Mehdi Hassan was born in a family of musicians in the town of Luna of district JhunJhunu in Rajasthan around 1927. Rajasthan is famous for its haunting melodies and the expanse of the desert, which celebrates man’s primal relationship with nature. Reshma is also from this region. Hassan’s father Ustad Azeem Khan and Uncle Ustad Ismail Khan were well known classical musicians and it is said that Mehdi Hassan’s first ever concert was at the Maharaja of Baroda’s darbar when he was just eight years old.

With Partition in 1947 this gharana moved to Pakistani Punjab. A young Mehdi Hassan took up the job of an automobile mechanic, something that he was supposed to have been quite adept at. But within a few years, it was his musical talent to which people began paying attention, and by 1952 he was singing at Radio Pakistan.

Mehdi Hassan remained a prized treasure of Radio Pakistan for nearly half a century. I remember growing up listening to his film songs, ghazals and thumris on radio. The launch of television in the 1960s provided an additional platform to Hassan and some of his memorable performances are from those black and white days of television programming.

Hassan proved to be a musical Midas. Whatever he touched turned to gold – from the poetry of famous Urdu poets to romantic film numbers.

The quality of his voice, controlled over the melody and the flawlessness of his musical renditions turned him into a demigod of film music. I have heard Bangladeshis praising Mehdi Hassan; Indians of course love him, and even in places where Urdu may not be widely understood it is difficult not to surrender to the magic of Mehdi Hassan’s mellifluous voice.

By 1960s, a special relationship between Mehdi Hassan and Faiz’s poetry had emerged. For instance the deeply lyrical “Gulon mai rang bhare, baad e nau bahar chale” by Faiz is a well recognized ghazal across South Asia.

Similarly Mehdi Hassan’s two other compositions, Hafeez Hoshiarpuri’s ghazal “Mohabbat karne waale kum na honge” and Razi Tirmizi’s “Bhooli bisri chand umeedein” are legendary for their composition and delivery. During his early career, he also popularised another Urdu Master, Mir Taqi Mir, and gave a new dimension to his simple, soulful verses. The best example of this remains “Pata pata boota boota hal hamara jane hai (Every leaf and every plant knows about my anguish”).

Judging by his repertoire, Hassan was the voice that connected the common musical and literary traditions of North India, which had metamorphosed into the bitter political rivals, India and Pakistan.

Noting the widespread appeal that Hassan’s voice garnered, Pakistan’s film industry was immensely enriched by Mehdi Hassan. At least for two decades he was the uncrowned king of the film songs, which were elevated to serious musical pieces simply by the magic of his voice. The two worlds of film music and ghazal rendition reinforced each other and even merged at times. For example two ghazals by Ahmed Faraz – “Ab ke hum bichre toh shayad kabhi khwabon mai milay” and “Ranjish hi sahi dil hi dukhane ke liye aa” – were rendered with extreme sophistication and mastery, akin to a miniaturist, for mainstream Pakistani cinema.

Folk genre

The other area of Mehdi Hassan’s boundless forte was his innate mastery of the folk genre. In particular, Kesaria Balam, the eternal Rajasthani folk song and even the Punjabi Kaafi “Bullah ki jana mai kaun” are two masterpieces that will always remain timeless in their appeal.

He adopted Karachi as his permanent home; and this is where his family lives now. I was fortunate to be part of a first ever book project on Mehdi Hassan published in 2011. In my essay, I stressed how Mehdi Hassan is not a vocalist in the traditional sense but his extraordinary voice and command over music was reminiscent of Tansen’s position in the age of the Mughal Emperor Akbar; and the latter’s various courts in Fatehpur Sikri, Agra and Lahore. Mehdi Hassan perfected the presentation of Raag Darbari (associated with Tansen) and popularised it in ghazals, geet and film songs. His true legacy was the continuation of rich traditions and innovations within the ambit of Hindusthani classical music.

Mehdi Hassan fought death for many years. It was a losing battle. But his immortality is ensured. Tansen must be proud of his New Age prodigy.

(Raza Rumi is a writer from Pakistan. His writings are archived at www.razarumi.com. Follow him on Twitter: @razarumi)