Mehdi Hasan died today. There are no words to capture his influence on my generation and the ones before me. I am posting a shorter version of my essay which was published in a volume “Mehdi Hasan: The Man and His Music” (2010, Liberty Books). RIP Khan Saheb. The kesari balam has finally left for his new home..

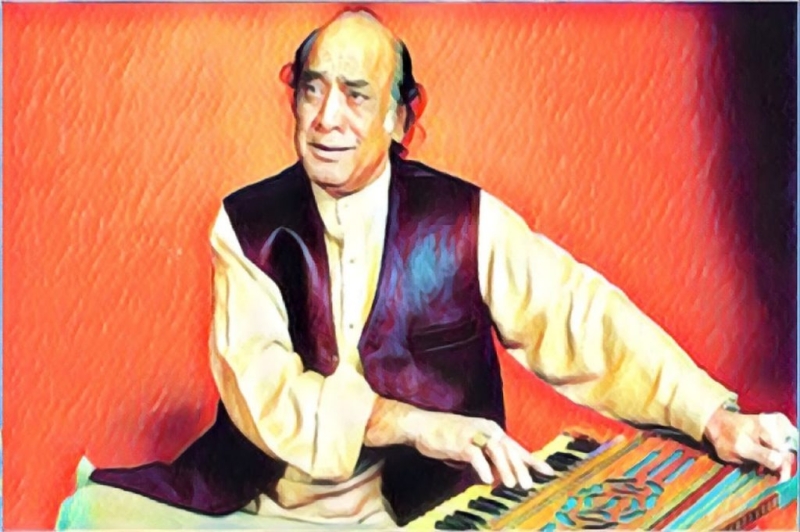

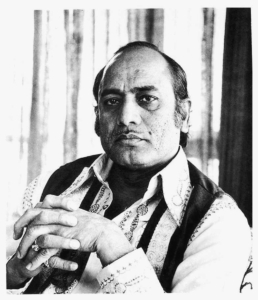

From Khyber to Dhaka and from Skardu to Deccan wafts a lilting and profound voice that binds discerning lovers of music. The highly trained vocals are none other than Mehdi Hasan’s, which leave music buffs like this writer wondering how Mian Tansen may have sung Raga Darbari, his own innovation, with full-throated ease and with what degree of perfection in Emperor Akbar’s court, be it in Agra, Lahore or Fatehpur Sikri. Listening to Mehdi Hasan’s flawless exposition of what is often referred to as the most royal of the ragas on which is based his composition of Perveen Shakir’s ghazal Ku baku phael gayi, one feels privileged to be living in the melodious age of Mehdi Hasan. But it is not merely Darbari that he excels in; name any other raga that he has garbed his ghazal in and you will not miss his flair for classical music.

His gift and skill are matchless. Alas, the voice is in silence for many years due to his protracted illness for nearly a decade

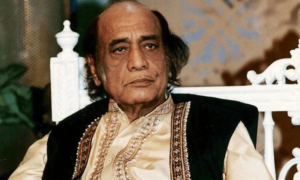

While the melody queen Noor Jehan reigned over the world of Pakistani film music, Mehdi Hasan retained his status as Shehanshah-e-Ghazal – an icon, a cult in the Pakistani musical universe. His gift and skill are matchless. Alas, the voice is in silence for many years due to his protracted illness for nearly a decade. The man behind this soulful, mellow and earthy voice has been an enigma, due, in part, to our general proclivity not to document the lives of the outstanding characters in our cultural life. On Pakistan’s culture, or lack thereof, the less said the better. Even at the best of times, we have been confounded by debates on whether music is haraam or halaal and where the glorious tradition of subcontinental Hindustani ends and the new Islamic state’s cultural ethos begins.

The debate, instead of getting resolved, has worsened with the rise of fully armed hordes of obscurantists, which are not just anti-culture but a threat to Pakistan’s existence as a pluralistic and vibrant society. Therefore, writing on music and tracing the footprints of a legend are an act of defiance in itself, challenging the orthodoxy and those who wish to remove melody from our lives. Rejuvenation and preservation of our fading cultural memory, needless to say, is essential to our survival.

Rajasthan is known for its haunting melodies celebrating the relationship between the earth and the soul. The echoes of nomads and banjaras roaming its deserts are said to merge into sand dunes and shining stars. And it was in the town of Luna, of district Jhunjhunu in Rajasthan, where Mehdi Hassan was born in a family of musicians in 1927 (Luna is close to 100 miles from Jaipur). His father Ustad Azeem Khan and uncle Ustad Ismail Khan were well-known classical singers and they also became his mentors and role models. Reportedly, Hasan’s first public performance took place when he was eight years old at the Maharaja of Baroda’s darbar.

I have met several men and women in Dhaka who while struggling to locate some positive memories of their united Pakistan experience point towards Mehdi Hasan’s songs and ghazal

After Partition, Mehdi Hassan moved to District Khushab in the Sargodha region in Pakistan and took a job as an automobile mechanic, perhaps explaining the scientific precision of his skills. However, the immense talent refused to be marginalised in the wilderness of the central Punjab. Within years Radio Pakistan glowed with his melody in 1952. This was the time when he sang the immortal ghazal ‘Gulon mein rung bharay baad-e-naubahar chalay’ by Faiz Ahmed Faiz. His elder brother, Pandit Ghulam Qadir, composed that ghazal and two other classics: Hafeez Hoshiarpuri’s ghazal “Mohabbat karne waale kum na honge” and Razi Tirmizi’s “Bhooli bisri chand umeedein“.

The state initially showed minimal interest in the treatment of Mehdi Hasan’s prolonged illness to the extent of being cruel

A formidable icon had emerged whose voice and mastery led the subcontinental diva, Lata Mangeshkar, to remark that Mehdi Hasan’s voice was divine (‘un ke gallay mein bhagwan boltay hain’ or something to that effect). With his credentials as a maestro established in a short span of time, Mehdi Hasan moved to film music where he was to enjoy a unique position as a playback singer. He was neither a pop star nor a film singer, as we understand today through the Bollywood lens. His was a musical soiree that was a blend of the popular and the courtly, of the sublime and the banal resulting in some of the best film music of Pakistani history. Perhaps one of the cultural bonds between the eastern and western wings of pre-1971 Pakistan was Mehdi Hasan’s music.

I have met several men and women in Dhaka who while struggling to locate some positive memories of their united Pakistan experience point towards Mehdi Hasan’s songs and ghazals. The repertoire of his film music was also wide-ranging and continued through the decades.

Earlier songs, ‘Aye roshnian ke sheher bata’ from film ‘Chinagri’(composed by Khawaja Khursheed Anwar), ‘Tu laakh chahe ai jaane baharan’ from ‘Najma’ (composed by Master Inayat), ‘ik naye mod per le ayen hai halat mujhe‘, (film Ehsan, music Sohail Rana) and the experimental ‘Mein hoon yahan tu he wahan’ from film ‘Gharnata’ (composed by A Hameed) set new standards for film music not only in Pakistan but throughout South Asia.

The songs memorable for their soulfulness among others were: ‘Jab koi piyar se bulaye ga’, ‘Yoon zindagi ki rah mein takra gaya koi’, ‘Mujhe tum nazar se gira tau rahay ho’, and, the ultimate piece of complete music, Ik husn ki devi se mujhe piyar hua tha’. Small wonder that Mehdi Hassan’s oeuvre is ever popular and rendered even today by young and new artists to make them accessible to the youth.

Even at the best of times, we have been confounded by debates on whether music is haraam or halaal

Pakistan’s perennially popular film ‘Aaina’ (with a lilting score by Robin Ghosh) acquired another dimension with the soft tunes and notes rendered by Mehdi Hasan. From the modern ‘Kabhi mein sochta hun kuch na kuch kahoon’ to the anguished cry ‘Mujhe dil se na bhulana’, his film music rises above the commercialism of cinema.

Even later, his film melodies were always in public demand and a dream project for any composer. A later film released in the early 1980s ‘Bandish had a brilliant song Do piyasay dil eik huay hain aiasay, bichrain ge ab kaisay.

The film journey, majestic and fulsome, as it was, benefited greatly from the parallel stream flowing in our cultural veins in the form of ghazals and semi-classical pieces. The two reinforced each other and even merged at many points. When the film music genre interacted with the ghazal idiom, the results were absolutely astounding. Two examples are the ghazals composed by Ahmad Faraz which were rendered with extreme sophistication and the adroitness of a miniaturist: ‘Abke ham bichray tou shayed kabhi khawabon mein milain’,and the masterpiece Mehdi Hasan based on the evergreen raga – Aiman – ‘Ranjish hi sahi, dil hi dukhanay ke liye aa’.

Be it Mir, Ghalib, Faiz or any of the long line of contemporary poets such as Parveen Shakir and Faraz, Mehdi Hasan had the innate art to bring out the best from Urdu’s versified poetry and its tender images. The ultimate of ghazals, a ‘piece-de-resistance’, is Mir Taqi Mir’s ‘Patta patta boota boota, haal hamara jaanay hai’, (composed by Niaz Hussain Shami) which remains an outstanding chapter of ghazal singing. Parveen Shakir’s first book ‘Khushbu’ received its greatest tributes in the form of Mehdi Hasan’s extraordinary rendition of ‘Ku baku phel gayee baat shanasai ki’.

His exposition of Raga Tilak Kamod in ‘Dukhwa mein kaase kahoon mori sajni’ is a sample of highpoints of semi-classical music. This composition testifies to the virtuoso’s genius for its effortlessness and sheer beauty. As if this incredible dexterity, range and diversity are not enough, Khan sahib’s essential command over the folk genre has been a spectacular treat. In particular, ‘Kesariya balama’, the eternal Rajasthani song delivered amazingly with the range and vastness of the Thar desert, is an imprint on our collective memory that refuses to fade away.

Mehdi Hasan’s richness of expression and superb career is a matter of our pride. His voice is what I grew up with. I remember my childhood when the radio, television, cinema and ‘mehfils’ were nothing but revered spaces devoted to Khan sahib. His popularity cuts across ethnic, provincial and linguistic divides.

But what did the state do? A mammoth entity inhabited by vested interests and anti-culture elements, the state initially showed minimal interest in the treatment of Mehdi Hasan’s prolonged illness to the extent of being cruel. The least that Pakistan’s officialdom could have done was to take care of its brilliant performer who added music to a turbulent and tumultuous country. But what came was only after the media picked up this story and forced the powerful lords of our destiny to give some attention to this issue. The voluntary response of our officials makes us ashamed of our larger national conduct.

But this has been our tragic tradition. Our greatest artists, singers, poets and intellectuals have suffered at the hands of a conformist society and state captured by puritans especially since late 1970s. It is never too late for the intelligentsia of this country to mobilise public pressure on the state machinery so that it learns to respect cultural diversity and the imperative to nurture a creative, healthy and civilised society.

Tansen taught us how music is a route to immortality. An ailing Mehdi Hasan in 2011 is fighting with death. His longevity is ensured. Tansen must be proud of his new-age prodigy.

An edited version was published in “Mehdi Hasan: The Man and His Music” edited by Asif Noorani (2010, Liberty Books) and later The Friday Times.

Raza Rumi is a writer and policy expert based in Lahore. He blogs at http://razarumi.com. Follow him on twitter: @razarumi