Mustafa: associate, companion, employee, friend

A year after gunmen attacked his car, killing his young driver, I mourn the loss of Mustafa

It has been a year since I lost a close associate, an employee, a friend. After I miraculously escaped a carefully planned announcement, there was much to celebrate: the chance to live, the experience of having defied death. But this living has come with a death at its very centre. Young Mustafa, who had still to experience life, was deprived of that. What can it be called? An accident? An assassination? Crossfire? Or the sheer randomness of death?

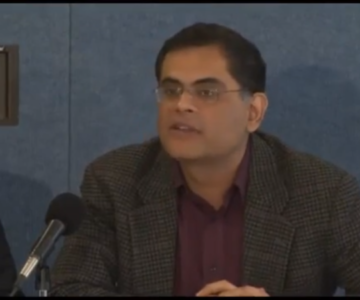

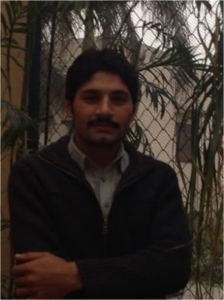

In 2008, on returning to Pakistan after a stint with the Asian Development Bank, I hired Mustafa. Another candidate, who could not work full-time, referred him to me. I was a little hesitant to hire someone so young but during the various tests, he proved to be a responsible driver and immediately endeared himself to my family, including my young children, who later became his friends.

He shared my enthusiasm for old buildings, random signs, rickshaw posters and pop art

Mustafa, a resident of Kasur, was the eldest child of a landless, working-class family. They had to stock wheat after every harvest, lived in a house that sustained damage after every monsoon, and faced the brutal marginalization of being who they were in the essentially classist rural society of Punjab. Mustafa’s venturing out to the city, therefore, added a bit of pride in addition to financial support for the family. He was choosing not to be a manual labourer, but opting instead for better-paid high-skill-based employment. I found out about all these nuances as we spoke about his village and the dynamics therein.

Within a year of working for us, Mustafa’s ailing father, paralysed after an accident, passed away. This made him even more worried about his family and the frequency of his visits to the village increased. His mother was next: after a year or so, she too died. Here was a twenty-something responsible for the household and his young siblings. Before she passed away, his mother had arranged his marriage to a distant cousin. It was a marriage of his choice as well: he had known his young wife-to-be since childhood.

As part of Pakistan’s new, well-connected youth, Mustafa had a rather adept relationship with technology. He would deftly use Pakistan’s low-cost telecom service provider, Zong, and its various packages to conduct long conversations with his family, friends, village wallas and fiancé. To enhance his “talk time” or “minutes” as they are known colloquially. He kept two mobile phones on him and when the limit on one SIM card had been exhausted, the other “package” was activated. I had to chide him on occasion as the earphones had become a permanent fixture of his persona. He would laugh and remove them.

His engagement with social media also came as an extension of his discovery of mobile telephony. Mustafa was a school dropout and, despite my repeated reminders, did not seem interested in pursuing further education. This was in contrast to another domestic helper who had agreed to study and will soon graduate with an arts degree. But Facebook came as a little wonder into Mustafa’s life, opening doors to global news mostly picked up through videos, memes and images. Often, he knew more about what was happening in Gaza or Iraq. A Bollywood fan, he even knew what its artists were up to and which films had been released with what storyline.

Mustafa also began to follow many sermons by popular clerics in Pakistan. There were discussions on the faith as well. But throughout, Mustafa’s adherence to the Sufi variant of Islamic faith remained steadfast despite the questions he picked up from the more puritanical versions, ironically via technological communication.

His village dargah of a local saint and Kasur’s famous shrine of Bulleh Shah were the two centres at which annual rituals were performed and I too contributed to the ceremonies. There was a rock-solid belief in peaceful, non-violent ideas that the Sufi legacy continues to inspire among so many people in Pakistan. It is not a coincidence that those who consider Sufi shrines spaces for infidels (and their ilk actually bomb them) reportedly killed him. Mustafa, too, albeit indirectly, was a victim of that ideology.

As his status grew in the village with the regular income he received, unlike the daily wages that are the norm for many informal workers in Pakistan, so did his quest to acquire a weapon for ‘safety’. The government has banned the issuance of arms licenses and exceptions, quite a few , are made when you have a strong recommendation from an elected representative or member of the bureaucracy. For months, he had wanted me to get him a license for a prohibited bore. I am anti-gun in theory and always wary of the idea of a gun traveling in the same car as me. Events have given me a reality check.

So when I moved to Express TV and there were increasing threats to the channel, I sought the help of a security guard who was also with us on that fateful day of Mustafa’s murder and my near-death experience. The Express Group was getting a deal from the Punjab Police whereby licenses were to be issued for security. I was finally going to get close to fulfilling Mustafa’s wish, but the opportunity never came. Before it materialized, he was gone.

All these years, Mustafa was not an ordinary employee. He was more than a family member, a playmate of my children, an administrative associate who helped me negotiate two cities, two homes, multiple careers and travels. He knew where my papers were and where my bills, forms and the entire daily grind was located. He was an ever-smiling, gentle shadow over my logistical existence. More than that, he was emotionally supportive in his own way. If I had yelled on the phone, he would bring me a glass of water. If I had not gone for my daily walk, he would remind me to. He would buy me snacks, “corn on the cob, bananas, jamuns and yogurt” between multiple appointments so that I could eat. So we were friends as far as the hierarchy could allow. I trusted him more than many I knew.

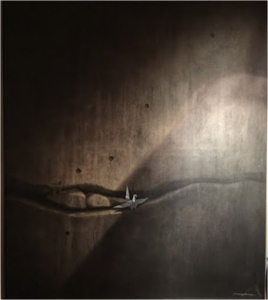

He was also my companion when I visited Sufi shrines as a regular feature of my Lahore life. Even on the night of 28 March 2014, we had planned a trip to Data Darbar. It was a special Friday night and it was he who had reminded me that day. He had, despite my protests, displayed a poster of the saints on the back window of the car. He shared my enthusiasm for discovering old buildings, for random signs, rickshaw posters and other forms of pop art. He would slow down and ask me to take a picture of an outlandish advert or a painting on a truck.

But he was taken away. A part of me, too, has died. I live with a haunting, gnawing hole in my being. There is not a day that his face does not appear while I am awake or asleep. Perhaps I am suffering from trauma. But this is accentuated by my being away from home, being afraid to risk another tragedy. More than my mortality, I am now obsessed with the idea that someone else might get hurt or even receive a minor injury on my account. I am on the radar of the militants and their handlers and this is a reality that I have to live with for some time. Why I threw conformity to the winds and whether it was all it is worth, is something I need to figure out.

Before I left Pakistan, I tried in my humble way to organize some financial support for Mustafa’s family. This too had its own dynamics and left me disillusioned once again with the darkest recesses of human behaviour. After I had left, the police arrested the alleged gunmen and Mustafa’s family had to undergo another ordeal: threats, pressure, and inducements. We remained in touch but I let them decide what they deemed best. I could neither insist on them giving false evidence, nor stop them, for the entire system of justice is the stuff of Greek tragedies.

And the most recent jolt. Mustafa’s younger brother was arrested last week by the police as a “suspect” in a local case of dacoity. They took him to the police station and tortured him for a night. A police official who lives in the area had apparently decided to teach them a lesson for not acting like the landless peasants they are. My family intervened to have him released and now another friend, a human rights lawyer, is working on his case. For the poor of our country, there is simply no protection. The torture has left Mustafa’s brother maimed. Medical care is poor in Kasur and so another transaction, another layer of exploitation “healthcare” has been added to the miseries of the family. I am a remote participant, sometimes effective and at other times not so useful. This is how it is.

A new report states that Pakistan has lost 80,000 people during the ongoing war on terrorism. Mustafa is a mere footnote in this sordid saga. I could have been a digit too. Human life and dignity, those meaningless, abstract terms one had learned, stand mocked and hung upside down where injustice prevails.

Thousands of Mustafas remain vulnerable at the hands of this extremist mind-set unless the state cuts the umbilical cord that gives the killers their strength, their impunity

A military court may actually hear this case now. The gunmen are in jail, but the mastermind, according to police reports as cited in the media, is in Dubai. He has a leader who heads a large, overwhelming militia. The militia was set up in the 1980s by the most powerful elements of the state. The task is an uphill one. The masked gunmen who fired at my car and killed Mustafa are unrecognizable. If the ones in jail are hanged, will this be justice? Perhaps in that vengeful moment or in a limited sense. But thousands of Mustafas remain vulnerable at the hands of the same mind-set unless the state cuts the umbilical cord that gives the killers their strength, their impunity.

In the meantime, I mourn Mustafa, celebrate his short, beautiful life, and pray that his family remains safe. I also pray that I might get over the image of his dead body as I tried to pull him out from the bullet-riddled car amid a melee unwilling to help.

One day, all this will change, I hope. But nothing will bring Mustafa back.