Irfan Habib from Delhi has shared the proceedings of a two day discussion that veered around several aspects of the problem, including the rise of minority communalism, tracing its beginnings and locating it in its present day political context.

MINORITY COMMUNALISM

Jawaharlal Nehru was categorical in his views about majority and minority communalisms. He considered majority communalism to be more dangerous and harmful to democratic processes than minority communalism. It seems that this Nehruvian construct is responsible for the present day emphasis on majority communalism, while minority communalism is merely perceived as a reaction emanating out of fear and insecurity. Thus, most of the strategies to combat communalism are confined to battling Hindutva forces while minority communalism is not treated that seriously. This approach has even provided the ruse for the majority to claim that minorities have been pampered. One of the most infamous episodes of Minority pampering is the Shah Bano case cited ad nauseam by the partisans of communalist politics in India.

However, it should be treated as an appeasement of the Muslim communalists and not the community as such, because the same government tried to pamper the Hindu majority communalists by opening the locks of the Babri Masjid leading to its demolition in 1992. Nevertheless, minority communalism is a reality and we need to know its beginnings and ramifications in Indian political context.

Muslims in India have always been a minority despite the fact that they were part of the ruling dynasties for a couple of centuries from 12th to the mid 19th century. Though we hear a lot about medieval atrocities committed in the name of religion, the Hindu majority lived in a fairly harmonious relationship with the minority Muslim population.

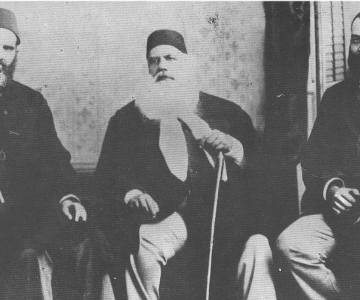

The question of Muslims as minority started gaining prominence after the British ascendancy from the mid nineteenth century onwards. The British took over in 1857 after defeating the joint resistance put forward by the Hindus and Muslims. One of the most serious aftermaths of the British victory was the identification of Muslims as the arch conspirators and enemies of the emerging colonial empire in India. Muslims, on the other hand, became conscious of their identity as a minority and could perceive some real and imaginary discrimination in the new dispensation. It can be safely said that communal consciousness in terms of majority or minority, came into existence from the mid 19th century onwards. The 19th century saw the birth of socio-cultural regeneration and consciousness and most of it was community based and was within the parameters of religion. One prime example is Syed Ahmad Khan, who was a great reformer and protagonist of Muslim welfare, and also a product of 1857 who became conscious of his Muslim identity when he saw the victimization of Muslims by the British. This was the beginning of Muslim communitarian politics in India, which was conveniently transformed into communal identity politics during the late 19th century after the emergence of nationalism and took ominous proportions during the freedom struggle leading to the partition of the country. Syed Ahmad cannot be accused of minority communalism as he was too deeply embedded in the ashraf culture of the 19th century Delhi; however the compulsions of the period transformed his agenda in the early twentieth century.

The late 19th and early twentieth century saw tremendous turbulence in the Islamic world and India could not remain unaffected by its impact. Meanwhile the British put their divide and rule policy into action by the partition of Bengal in 1905, making an open claim that it will provide more job opportunities to the Muslims. It served the purpose and the resurgent Muslim communalism led to the founding of Muslim League in Dacca in 1906. Despite a large number of anti-partitionist Muslims, the whole region witnessed widespread communal violence. Soon India was trapped in the pan-Islamic movement in support of the Turkish Khalifa, as the British had put some harsh conditions before the Sultan. The Khilafat movement polarized the Muslim population in India, and the Khilafat leaders managed to rope in the Mahatma and the Congress party for their Khilafat cause. Khilafat issue became one of the agenda items for the non-cooperation movement launched by the Congress. Its abrupt withdrawal by Gandhi led to the communalization of Indian polity and further strengthened the Muslim minority consciousness, which had been on the rise since the turn of the century. As one of the participants pointed out, the Khilafat cause led to the emergence of communal politics in Kerala, the Khilafat movement turned violent in Malapuram. I need not go into further details to map its beginnings as the late 1920s and 30s saw its ugly rise, ultimately leading to partition in 1947. The post- independence India was declared a secular republic but we inherited the troubled legacy of communalism, both minority as well as majority.

With this legacy, India had passed through some very distraught phases during the past fifty years, where the issue of communalism occupied centre stage. I do not wish to make a simplistic assertion that minority communalism grew only as a reaction to majoritarian communalism; nonetheless it had an important role in its spread. Actually they need each other to grow, and we have innumerable examples in independent India where they have unabashedly fed each other. The compulsions of democratic governance have forced the political parties to use the minorities as potential vote banks, while no serious attempt has ever been made to mitigate their pain. The various forms of discriminations against the Muslims have had a ruinous impact on the thinking of considerable sections of the community. The failure of the secular state to provide security, the compromise of bourgeois secularism with communal forces and the offensive of majority communalism has led to the emergence of communal and fundamentalist elements among Muslim minority. The Tablighi Jamaat and Jamat-i-Islami had been around since the 1930s but they were catapulted to centre stage during the 1980s and 90s. We should not forget that the same period saw the increasing relevance of RSS as the key player in Indian politics. They have also been around since the 1920s and were known as the fringe or the lunatic fringe of Indian polity; however, it was the unfortunate politics of these two decades that not only gave them wider acceptability but also a stint in governance.

The participants in the Consultation raised several issues through their personal experiences as well as through general observations. The Muslim sectarian organizations have increasingly become hegemonic, where individual’s role in decision making has almost disappeared. Most of these fronts tend to take initiatives on behalf of the community and impose them through their dictat. During the discussion, it was reported by some participants that a conference of Muslim women in Bhopal ended up advising women to wear burqa, say regular namaz but nothing about the plight they go through in their daily lives. The implication of such initiatives is, as reported by another participant during the consultation, that women are subjected to dress codes in AMU and are not allowed free participation in the university activities. The participants were of the view that the Shah Bano case was further communalized by organizations like the Muslim Personal Law Board as they took a retrograde stand on the issue and provided fodder to the Hindu majority communalists. The issues like poverty, education and the predicament of women are not addressed by any of these Muslim organizations.

Quite a few participants felt that Muslim communalism is related to the increasing relevance of the community in independent India, as most of the political parties see the minorities as a force to be reckoned with. The elitist leadership is out of sync, and has no touch with the average Muslim. A Kerala Muslim participant pointed out that the Muslim League had not been a communal party till a decade ago but now the situation is fast changing, and it is due the global Islamic politics, and is also impacted by post-Ayodhya and post Gujarat scenario. For example, Jamaat-i-Islami was in Kerala since 1948 but it gained strength after 1992.

The growth of Muslim fundamentalism in the neighbouring countries like Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh and in areas beyond the sub-continent, besides the real and imagined wrongs perpetrated in Kashmir, have also played their part to perpetuate this retrograde and self-defeating thinking among the Muslims. It may not be as hegemonic as majority communalism but it is equally dangerous and condemnable. Unfortunately, its growth provides further nourishment to majority communalism and they end up being complementary to each other.