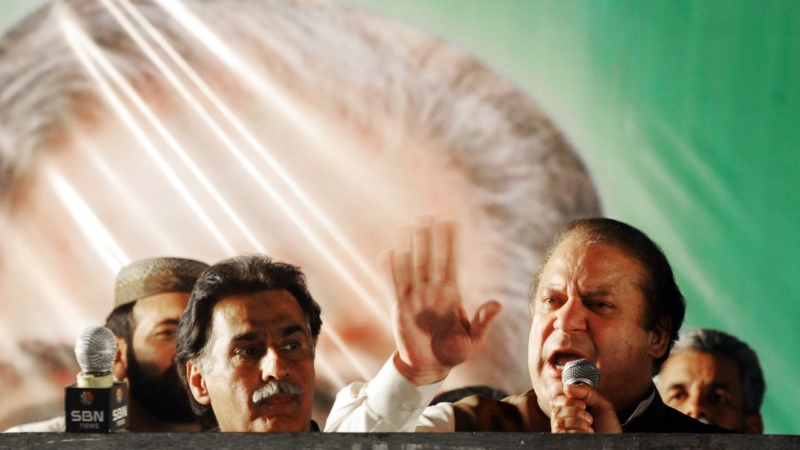

CNN’s Jethro Mullen weighs in on Nawaz Sharif

The strongest contender to become the next Pakistani prime minister is hardly a newcomer to the country’s political stage.

Nawaz Sharif, 63, has had a long and rocky career that includes two stints as prime minister during the 1990s, ordering Pakistan’s first nuclear tests, a showdown with the nation’s powerful military, time in jail and years of exile.

After spending the past several years in opposition to the governing Pakistani People’s Party (PPP) — which has struggled to tackle the country’s crippling problems of militant violence, chronic power shortages and a flagging economy — Sharif now has a shot at another stint in office.

But observers say his positions on key issues such as Islamic extremists and relations with the United States remain vague, raising uncertainty about what kind of approach he would take if his Pakistani Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) were to succeed in forming a government in the national assembly following general elections this weekend.

There is also concern about his relationship with the military’s top generals, who still maintain a strong influence on Pakistan’s foreign and security policies.

Interventions by the military ended Sharif’s terms as prime minister in 1999 when Pervez Musharraf, the head of the army at the time, overthrew him in a coup.

In a dramatic fall from grace, Sharif ended up in jail, convicted of hijacking charges for trying to stop a plane carrying Musharraf from landing. He then went into exile in Saudi Arabia and didn’t return to Pakistan until 2007, when he teamed up with the PPP to force Musharraf from office.

“It’s a big question whether he can coexist with the military,” said Zahid Hussain, a veteran Pakistani journalist and author. “He hasn’t forgiven or forgotten what happened to him.”

All about the economy

Sharif’s campaign has focused on the economy, which seems to matter the most to many Pakistanis. The nation ranks 146th out of 186 countries in the United Nations’ human development index, a measure of living standards, health and education.

Under the slogan “Strong Economy — Strong Pakistan,” Sharif is playing to his image as a flag-bearer for private industry and entrepreneurship. Part of a prominent industrial family, he took steps to liberalize the economy during his time in office in the 1990s through measures such as privatizing state-run companies.

“Generally, the business lobby has more confidence in his ability to fix the economy and solve some of the trickier problems, particularly the energy crisis,” said Raza Rumi, director of policy and programs at the Jinnah Institute, a Pakistani research organization.

His party has built conspicuous infrastructure projects in recent years in its political stronghold of Punjab, which is home to more than half of Pakistan’s 180 million people and the biggest source of elected seats in the National Assembly. It’s also the country’s industrial and agricultural heartland.

The Taliban question

While his economic credentials appear stronger than those of his main rivals, critics have picked up on his apparent reluctance to take a strong line against violent extremists, notably the Pakistani Taliban, who have carried out relentless, bloody attacks in the area bordering Afghanistan.

“He criticizes terrorism, he criticizes the use of force, but he will not criticize a specific organization by name,” said Hasan Askari Rizvi, a political analyst focused on defense issues. “He will not criticize the Pakistani Taliban by name.”

Sharif was not available for an interview for this article. But Irfanullah Khan Marwat, a veteran Pakistani politician who recently joined the PML-N, said that the party is in favor of holding talks with the Taliban.

“We as a party oppose extremism, we oppose bloodshed,” Marwat said. “And we think any and every solution lies with who is sitting across a table and coming to an understanding.”

The politics of fear

Sharif’s party’s cautious stance on the Taliban and other militant groups results from political expediency and fear, according to Rumi, who is also the editor of The Friday Times, a weekly newspaper.

Religious conservatives, some of whom sympathize with extremist groups, make up an important part of Sharif’s core vote, Rumi said. During his time in office in the 1990s, Sharif caused alarm among more secular-minded Pakistanis by pushing through legislation that sought to introduce aspects of Sharia law.

And since the assassination of former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto during campaigning for the 2008 elections, a lot of Pakistani politicians are afraid of well-organized, merciless militants like the Taliban, according to Rumi.

The killing of Bhutto is still being investigated by authorities, but the Taliban and other militant groups have between them carried out dozens of deadly attacks on campaigners for the current elections.

Uncertainty over relations with U.S.

An unwillingness to continue the fight against insurgents could put a Sharif government at loggerheads with the military and also strain already difficult relations with the United States, a key prop for Pakistan’s shaky public finances.

Sharif has openly questioned Pakistani-involvement in the American-led “war on terror.”

But observers note he may adapt his approach if he becomes prime minister.

“He had good working relations with the United States in previous terms,” Rizvi said. “My feeling is he will still have good relations. Once he gets into power, then he has to change.”

For its part, the United States says it has no preferred contender in the elections.

“We do not support any particular political party or any individual candidate, and we look forward to engaging the next democratically elected government of Pakistan,” Patrick Ventrell, a spokesman for the U.S. State Department, said last week.

A new approach to New Delhi?

Sharif has also raised eyebrows by vowing to improve ties with Pakistan’s archrival, India. The two nuclear-armed neighbors have fought three wars since their partition at the end of British colonial rule.

One of those wars, in 1999, led to the military coup that drove Sharif out of office.

In a recent interview with the Indian broadcaster CNN-IBN, Sharif said he would carry out an investigation into the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai, which killed more than 160 people.

India blames the Pakistan-based group, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, for carrying out the attacks, accusing Islamabad of not doing enough to pursue its members. The group has denied responsibility.

Democratic progress

If a new Pakistani government is successfully formed from the elections this weekend, it will be the first time in Pakistan’s history that the country has democratically transitioned from one elected administration to another.

One of the reasons for that, analysts say, is that Sharif and his party took a pragmatic approach to being in opposition, despite their differences with the governing PPP and its leader, President Asif Ali Zardari, Bhutto’s widower.

It’s a far cry from the 1990s, when Sharif and Bhutto worked constantly to undermine each other’s governments, resulting in instability and interference from the military.

The 21st-century Sharif, mindful of his overthrow and exile, appears more committed to upholding democratic, civilian government and not providing the military with an excuse to step in, according to Rumi.

“That by itself was a very promising development,” he said.

The trouble with coalitions

The big question, however, is how effective any government that emerges from the elections will be.

Although several opinion polls have put Sharif’s party in front, a great deal of uncertainty remains over how many seats it will end up with in the assembly.

Observers say there’s a strong chance that both parties will fall short of an overall majority, resulting in a scramble to form a coalition with smaller parties.

The most prominent and potentially game-changing of the smaller parties is cricket-star-turned-politician Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), a new player in national elections.

Analysts are finding it hard to predict how many seats PTI candidates might secure, especially after Khan was seriously injured in a fall at a campaign rally this week.

If his party wins enough seats, the former captain of the Pakistani cricket team could find himself the kingmaker in its parliament.

But any coalition government may struggle to formulate strong policies on the critical issues Pakistan faces, even under an established figure like Sharif.

That could leave other institutions with room to exert their influence.

“Theoretically, the prime minister is in charge,” Rumi said. “In practice, the military is more powerful.”