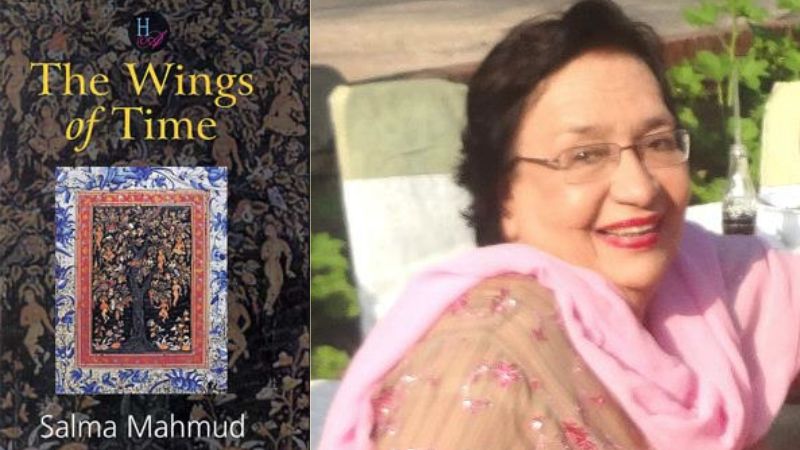

Salma Mahmud’s new book is not a just a readable memoir, it sets a standard for fine writing.

Perhaps the most memorable time of my career as a media walla is to have worked with Salma Mahmud as a fellow editor and writer. Her writings for TFT have been noted far and wide, eliciting feedback from celebrities to obscure readers across the globe. While she was completing a series on her great ‘Uncles’ (friends of her eminent father M D Taseer), I suggested that these memoirs be turned into a book. After initially feigning scorn at the idea, she relented; and now we have Salma Mahmud’s ‘The Wings of Time’ – a book that is pleasurable for its sparse yet lyrical writing and valuable for the histories it puts together. These reflections and anecdotes would not appear in Pakistan’s official and highbrow historiography as the intent of the book is different. It is a recollection and a reclaiming, with lots of indulgence and warmth.

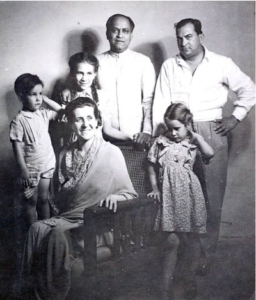

Salma Mahmud, or Salma-ji, as I call her, is the eldest child of Dr M D Taseer, the noted poet and critic, the first Indian to obtain a PhD in English from Cambridge University. Her other sibling, the late Salmaan Taseer, also made his mark in Pakistan as a brave defender of human rights and offered his life while fighting bigotry against the powerless of the country. Salma was born in Baramula, Kashmir, and was later educated in Lahore where she attended the Kinnaird College before pursuing a Masters degree at the University of Edinburgh. Mahmud is considered a seasoned teacher of the English language and literature and her facility with words made her an ideal editor at TFT. During her career, she has also translated several pieces of Urdu fiction into English and written extensively on literature, history and art.

As a quintessential daddy’s girl, Mahmud’s reverence for her father is evident throughout the book. At the same time, she doesn’t lose sight of the political and cultural context in which Dr Taseer lived and worked. She narrates the story of his times with exceptional honesty; illustrating the “the irreplaceable literary milieu in which he lived.” Indeed, the period of 1930-1950 witnessed immense turbulence but also gave birth to various literary and cultural movements. As the book and its rather deftly veiled melancholy mood tells us, the “milieu has vanished forever”. Mahmud chronicles this sadness and celebrates the histories of “a bevy of brilliant intellectuals who filled the existential void that existed within” Taseer due to his “aloneness”.

Mahmud’s mother, Christabel George, whom Taseer met at Cambridge, descended from a talented Huguenot family on her maternal side. She was the poet’s companion until his death in 1950. Her role in bringing up the three children was not less than heroic and Mahmud is rightly proud of her familial heritage: the complete package of literary taste, fondness for books and ideas and of course humaneness.

The first part of the book, titled Prologue, has four chapters that provide a fine account of the luminaries whom Mahmud met as a child and continued to know and appreciate as she grew up. The sketches of her ‘uncles’ are unparalleled. For instance, we find out how writer and educationist Pitras [AS] Bukhari single-handedly saved UNICEF “from being closed down by the US government in 1952, when he made a spirited defence of the organization during a UN committee meeting.” Bokhari was our representative at the UN immediately after the creation of the new state. Mahmud writes that after hearing Bukahri’s defence, “Eleanor Roosevelt was so impressed by his eloquence that she declared the United States had decided to let UNICEF remain.” Having written about Pitras here and there, I felt completely ignorant as I found out from Mahmud that on Pitras’s grave in Westchester, this couplet by Robert Frost, written personally by the poet for Bukhari, is engraved upon the headstone:

Nature within the inmost self divides

To trouble men with having to take sides.

The narrative is beautiful; it reads like a breezy work of fiction. The great poet Iqbal comes to life here as a human being (contrary to the deification that Pakistan has bestowed upon him to justify a pseudo-Islamist identity) and his association with Sufi Ghulam Mustafa Tabassum, a poet less remembered, is also recounted. Sufi was an exclusive part of Iqbal’s inner circle and was “allowed to take an occasional puff from Iqbal’s hukka.” Faiz was also mentored by Sufi and it is little known that the early works of Faiz were corrected by Sufi (also known as ‘islaah’ by a Master) and he deeply influenced the traditionalist-modern hybrid idiom that is the hallrmark of Faiz’s work. Sufi’s poetry is lost and is unavailable. Such are the ironies of literary movements.

Iqbal was very close to Taseer, and Mahmud writes of an “emotional relationship” between the two. Iqbal spoke of Taseer “as one of the young writers in Urdu from whom he expected great achievements”. Mahmud also tells us that her parents’ marriage contract, the nikah nama, was drafted by Iqbal: “he was Qazi at their marriage, incorporated the best Islamic values, in which he gave the right of divorce” to Christabel (Bilquis), Mahmud’s mother.

Dr Taseer’s association with and eventual disengagement from the Progressive Writers’ Movement is also narrated in the book. We learn how in London of 1935 Dr Mulk Raj Anand, future communist revolutionaries Jyoti Ghosh and Pramod Sengupta, Syed Sajjad Zahir and M D Taseer congregated at the Nanking Restaurant on Denmark Street in Soho “to draft the manifesto for the Progressive Writers’ Association.” As Mahmud says, Taseer later in life “distanced himself most forcefully from the Association’s activities.” In a later chapter, she explains how Dr Taseer not unlike several other ‘liberal’ writers came “to believe that their concepts were working against the very foundations of the fledgling state, regardless of any consequences.” This was a tragic departure after the creation of Pakistan as the state with such support was able to construct a national security paradigm. It is a bitter lesson that repression of the Left in the early years of Pakistan led to a series of events which have resulted in today’s mess. But that is another story. This book steers clear of such controversies and attempts to remain neutral in its tone.

Mahmud is adept at recollecting the ambiance of the cities that she lived in. Lahore, Delhi and Srinagar emerge as stories in their fullest form. Consider this, for instance: “New Delhi in the pre and post World War II era was a beautiful and elegant city. Most of its public buildings had been designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, but a large part of its residential areas were built by Sir Sobha Singh, father of Khushwant Singh the eminent journalist. The wide tree-lined avenues of the city and its colonial bungalows were flanked by Lodhi Gardens Estate, of which Lodhi Road was a part, and where Daddy was allotted a spacious four bedroom bungalow, number 58, and it was here that a splendid dinner for E.M. Forster was held in 1946. Those who attended included A.S.Bukhari, and also Majeed Malik, a dear friend from the Lahore days. It was here that the great novelist very affectionately asked me to call him Uncle Morgan, thereby entering the ranks of my many uncles. His full name was Edward Morgan Forster.”

In that quick paragraph, so much has been encapsulated; and this is the strength of “The Wings of Time”. It avoids verbosity and unnecessary details to keep the writing taut. The book then delves into family histories, elaborates who Christabel Taseer and her sister Alys Faiz were. Mahmud also looks into her family tree and there are some charming descriptions. For example, this elegant passage:

“Perhaps I ingested these stories before I was born. A fanciful thought, but after all there were many intriguing events connected with the story of Christabel and Taseer during the fifteen years of their idyllic relationship. And so the tale went on, from the day my mother set sail in late September 1936 on the Anchor Line S.S. Circassia from Tilbury Docks bound for faraway Bombay via Suez. There was a group of anxious and concerned padres on board who considered it their religious duty to urge her to reconsider her radical decision every time the ship stopped at a port from Marseilles onwards. ‘Go back home!’ they advised her, but my mother’s eyes were firmly set on the exciting and eventful days that lay ahead.”

The description of how Alys and Faiz got together gets a similar, though not as romantic, treatment: “Soon after Aunty Alys had settled in, the advent of World War II prevented her from returning to London, and so it was fated that she and Faiz the poet should fall in love and get married in 1941. The ceremony took place in Srinagar, where Daddy was by then Principal of a new educational institution. Sheikh Abdullah, then called Sher-e-Kashmir, was the Qazi at this ceremony, which was performed in the annexe of Maharaja Hari Singh’s marble palace, which had been allotted to us for some months”. The acute sense of history and intricate understanding of art, architecture and politics makes the book all the more readable.

The detailed exploration of Mahmud’s Huguenot maternal ancestors (who took refuge from religious persecution in France) in England is a brilliant story. Her Crucefix ancestors and family tree has been painstakingly reconstructed in the book. This meeting of civilisations and cultures in the lives of the Taseers makes them rather unique in the mono-culture-ridden Lahore of post-1947.

The events of 1947 were traumatic for the characters of this book. Dr Taseer survived three years of the new country and his death left the family in a new phase of survival and adjustment. The most touching account of these times is best exemplified by the passage in Chapter 11 when Dr Taseer receives a “most heartbreakingly poignant package from a riot-torn Lahore.” Mahmud’s description is evocative: “It was a tightly wrapped bundle of cloth with a fragile twisted thread at its heart, a home-made rakhi woven by Nirmala, the sister of family friend Premnath Kohli…That August, when Raksha Bandhan came, and the rivers of the Punjab were running red with blood, the Kohli family were trapped in their inner city home, but Nirmala did not forget her Rakhi brother, and smuggled out her package to Srinagar…” These stories of human bonds beyond religious identities are the richest as well as the most tragic element of our history.

After Taseer’s death the formidable Christabel decided to stay in Lahore, a city “that Daddy had always loved so much, and bring up his children as Pakistanis.” Mahmud tells us of the tribulations her mother underwent in supporting the family “as best she could, ensuring that her children were well-educated.” Mahmud rightly says that Christabel’s “courage in the face of adversity” must be remembered. But Mahmud’s wit is present even in the somber descriptions: “Never forget that she [Christabel] was a Huguenot by descent, and this race includes Sir Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, among many other notables, as well as two ferocious Caribbean pirates, one of whom was nicknamed The Exterminating Angel.”

Mahmud’s book ought to be read and disseminated through multimedia tools for the benefit of younger Pakistanis who unfortunately have been raised on a diet of lies and doctored histories. She recently quipped: “Today, when I teach an English class, I am confronted by students who proudly state that they hate reading and have never read a book in all their lives. At most they will have read The Alchemist, which I have sworn never to read.”

These cathartic and original memoirs are a significant addition to English writing from Pakistan. The text also sets a redoubtable benchmark for other Pakistani writers who have adopted this ‘global’ language for self-expression.