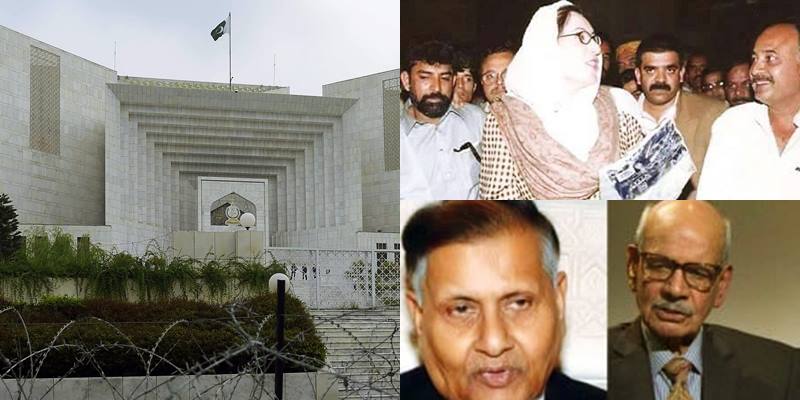

“We cannot have an army or intelligence agencies that constantly destabilise governments. We cannot have rogue elements incessantly violating their oath and plunging the nation into crises” – Benazir Bhutto (Herald, 2000)

Evidently, the state of Pakistan is rotten when its former Chief of the Army Staff, who does not stop touting himself as a true patriot, prima facie, violated the constitutional oath he undertook. It is not just Mirza Aslam Beg whose nefarious involvement in politics has been the subject of discussion in the courts and TV channels but countless others in Pakistan who have been upto similar transgressions and getting away with them.

After the death of Gen Ziaul Haq in 1988, military rule only changed its clothes. It survived and flourished for a decade until the Emperor threw off his civilian façade and took over in 1999 through a proper coup d’etat citing the same old excuse of saving the country. The history of 1988-1999 is yet to be written for it has remained hostage to the obfuscations of a political class created by the army itself and its loyalist intellectuals who rule the media and are found in Pakistan’s moribund academia as well.

The recent political glasnost in Pakistan – thanks to the lawyers’ mobilisation and the refusal of two major political parties to repeat their mistakes – is a new chapter in our history. Whether this is an illusion or a temporary triumphant moment, remains to be seen. The Supreme Court has, after a criminal delay of sixteen years taken up the Asghar Khan petition. The ‘free’ and independent Supreme Court did not take up this pending case until there was sufficient public pressure in the recent months. The judges have been remarking that they are representing ‘people’s will’ and perhaps this is why they are now establishing that they are truly independent and not taking cues from their erstwhile senior partner the military-intelligence complex. This is a welcome development and, if taken to its logical conclusion, might reset the way power dynamics have been structured in Pakistan.

After 1988 elections, it was clear that the junta, despite losing its greatest Machiavellian leader, Zia, was in no mood to transfer power to a civilian government. The story of Benazir Bhutto’s first ill-fated government (1988-1990) has been well documented by her advisor Iqbal Akhund in his book entitled, Trial and Error: The Advent and Eclipse of Benazir Bhutto (OUP Pakistan, 2000). The book, among other things, reveals the severe limits of Bhutto’s powers and outlines how she had little control over core governance areas such as security and economic policies.

During this time, there were two serious attempts to oust her: first, through a vote of no-confidence where the rogue intelligence officials doled out money to engineer the outcomes. The name of one Osama Bin laden was also cited as a potential financier of this effort. Bhutto’s government also indulged in horse trading given that was the ‘set’ game in town. In a hard-hitting interview given to monthly Herald (in 2000), Bhutto recounts the years in these words:

“..in December 1988, within a week of my forming the government, Brigadier Imtiaz, working at the ISI Internal, began contacting political parties to overthrow my government. My political adviser at the time, General Babar, moved to have him replaced. The army refused initially, though later, Brigadier Imtiaz was removed from the ISI Internal, not from the army itself…We collected proof, in 1989, of ISI elements visiting MNAs for a no-confidence move. We made audio tapes. The head of the MI entered my office and saw the photograph of the man who had been approaching my MNAs. He panicked, took the photograph and the tape and then sent me a report saying the man in question was deranged. In 1990, when the ISI launched a similar effort, we made a videotape called Operation Jackal. A serving army officer, Brigadier Imtiaz, technically not in the ISI but substantively still there, was taped saying: “the army does not want her, the president does not want her, the Americans don’t want her”. He was seeking the support of parliamentarians to oust the government. I gave that tape, substantive proof of treason, to General Beg. He filibustered.”

The second attempt was through a failed coup. The storyline was simple. Bhutto, as a people’s representative could not be trusted and she was a security risk for the deep state which wanted the continuation of jihad even after the demise of the Soviet Union. The priorities of the civilian governments could come into conflict with this sooner than later. It is not surprising that Pakistan’s most progressive scheme, budgetary constraints notwithstanding, of hiring and fielding village level lady health workers was initiated during these turbulent twenty months of Bhutto’s reign. This programme has continued ever since and its beneficial impact has been noted globally.

However, after her 1990 ouster, Bhutto had to be kept away from power. So the military chief Gen Aslam Beg, as details have re-emerged, played a direct and proactive role in ensuring that her right wing opponents (not too averse to the jihad paradigm) were returned to power.

Apparently, Rs14 crore were distributed by the ISI chief General Asad Durrani to opposition politicians. This is a small amount as more details trickle in and some estimate that the total quantum of funds used for political engineering may reach Rs1.4 billion. General (Retd) Naseerullah Babar, the Interior Minister in the PPP’s second government, collected the record and Air Marshal (Retd) Asghar Khan initiated this case.

The key man arm-twisted was Younis Habib, a banker who has now confessed that he was asked to raise Rs350 million by the former president Ghulam Ishaq Khan and the army chief before the 1990 general elections. Out of the Rs345 million ‘raised’, Rs140 million was paid through Gen Aslam Beg.

The Constitution in Pakistan is clear. It was even as unambiguous when Gen Beg was at the helm of affairs in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The oath of members of armed forces as enshrined in the Constitution’s Third Schedule reads as under:

“I….do solemnly swear that I will bear true faith and allegiance to Pakistan and uphold the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan which embodies the will of the people, that I will not engage myself in any political activities whatsoever and that I will honestly and faithfully serve Pakistan in the Pakistan Army (or Navy or Air Force) as required by and under the law.”

How many times was this oath violated? First, Gen Beg is on record to have sent a message to the Supreme Court in 1988 not to restore Prime Minister Junejo’s government. The message was sent through none other than the longest-serving chairman Senate Wasim Sajjad who ‘advised’ the Court. Later, a contempt petition against the ex-COAS was brought before the Court, but the Supreme Court was reluctant to proceed against Beg. It was widely believed though with no hardcore evidence that the GHQ had saved its former military chief. Honour comes with traditions.

Not content with this victory, Gen Beg and his team indulged in pure politics and that too with an ideological bravado. As Khaled Ahmed has written recently, “Aslam Beg was essentially an adventurer and a soldier of fortune shaped by Pakistan’s revisionist doctrine of defence who could not win against India playing according to rules of professionalism.” Thus, the affinity with local and global jihadis was at the back of sabotaging democratic process and hurting the way Pakistani state functions.

This diarchy of governance continues. The de facto powers to govern and take decisions still reside with a small coterie of unelected generals, bureaucrats, big business and a handful of pliant politicians. Now that the Supreme Court is asserting its space within Pakistani state structure, it is welcome as long as it establishes civilian ascendancy. The de jure arrangements are clear. A Parliament, the repository of people’s will and its elected cabinet has the legitimate right to govern and take executive decisions. Any other formulation will only continue the dysfunctional governance.

Pakistan’s assertive Supreme Court faces the most challenging choices today. By opening up the Asghar Khan case, it has enhanced the possibilities for correcting our course. But its justice must be ‘complete’ – as enshrined in the Constitution. At the very least, the army officials who violated their oath and politicians who squandered public funds must be brought to justice. Anything less than this would disappoint all of us who are hoping that the judges will not let history repeat itself.

Bhutto’s haunting words – “rogue elements incessantly violating their oath and plunging the nation into crises” -make even more sense nowadays after the agencies’ tricks such as memo affair have backfired. The paralysis of governance for months ultimately affected the ordinary citizen whose priorities such as security, employment and basic services are yet to be fully addressed by a dysfunctional state.

First published in The News on Sunday 18 March 2012