Pakistan’s economic crisis poses a great challenge for a coalition government struggling to keep the country afloat. The country’s foreign exchange reserves lurk around $3 billion, barely enough to finance 18 days of imports. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is expected to sign off on yet another bailout package for Pakistan. This may provide temporary reprieve for the dollar starved economy, but with external debt piling up fast, and payment obligations of $20 billion to be made by December 2023, it seems that even the IMF tranche would not substantially assuage concerns over Pakistan’s balance of payments.

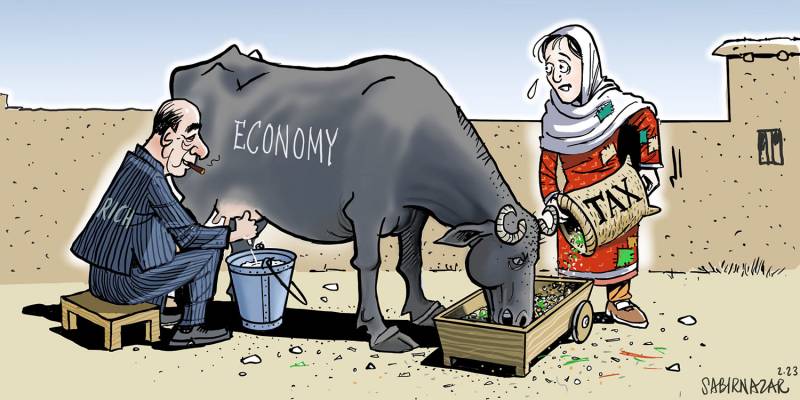

The Parliament has approved a bill levying taxes and excise duties to meet the IMF condition of mobilizing an additional Rs 170 billion of additional tax revenues. The bulk of this revenue will come through the applicable sales tax rate, a type of an indirect tax, which has been increased from 17% to 18%. Concurrently, the government has also implemented a price hike in petroleum products, to contain the flow of runaway circular debt in the energy sector.

Given constraints centered around debt, trade deficits and inflation, what appears to be a balance of payments crisis is in effect a crisis of governance.

The rupee was already devalued to meet the IMF demand of leaving its valuation at the mercy of market forces. The net devaluation in recent months has been more than 30%, and this is proving to be a major driver of inflation which was recorded at 27.3% in January 2023, calculated year-on-year.

The dollar value impacts transportation of goods and services, imports that the manufacturing sector relies upon, and necessities such as cooking oil and tea. Many of Pakistan’s exported goods themselves use imported raw materials and, therefore, even a 1% devaluation has a multiplier effect. The country’s exports, $31 billion in FY 22, are not increasing, while its imports, $80 billion in FY 22, are inelastic, thereby leading it into a perennial shortfall of foreign exchange and pushing it into a literal ‘debt trap’.

With the exit of the United States from Afghanistan, and no immediate security imperative of the West, Pakistan’s elites have been left high and dry, leaving those beneath them even worse-off.

Given constraints centered around debt, trade deficits and inflation, what appears to be a balance of payments crisis is in effect a crisis of governance. Successive governments have failed to invest adequately in developing a skilled, healthy and educated workforce. Instead, they favored powerful groups and entrenched vested interests, and ensured that shady lobbies prospered at the expense of the taxpayer.

Injections of aid from the developed world since the 1950s have helped maintain the status quo. The elites – particularly the military, the political class, large landowners and corporate industrialists – have ruled the country and have resisted reforms focused on restructuring of the taxation system, or investing in education, science and innovation, to create an export-led economy. With the exit of the United States from Afghanistan, and no immediate security imperative of the West, Pakistan’s elites have been left high and dry, leaving those beneath them even worse-off.

A 2021 study by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) cautiously estimated that the privileges and entitlements enjoyed by Pakistan’s elite were worth more than $17 billion per annum. This figure included benefits given out to real estate barons, the pampered industrial sector, and the military’s corporate holdings, among others. The privileges they still enjoy today take the form of tax breaks, cheap input prices, higher output prices, or preferential access to capital, land, services, and even to some local markets. These privileges inevitably make the ‘rules of the game’ irrelevant, turning Pakistan into an unattractive destination for investment or innovation.

The biggest recipient of state-financed privileges is the country’s corporate sector, accruing an estimated $4.7 billion per year. The second and third-biggest recipients of privileges were the country’s richest ‘one percent’ – collectively owning 9% of the country’s total income – and the feudal land-owning class – composed of 1.1% of the total population, but owning 22% of all arable farmland.

The rich landowning feudal class has always maintained a strong presence in Parliament. Most major political parties draw their candidates from a pool of ‘electables’ that usually hail from the feudal landowning elite classes. Control of land, capital, and caste networks are the usual determinants of victory in many democratic contests across Pakistan, especially in the rural areas.

In addition to the state’s financial support through a massive chunk of the budget, and tax breaks for military-affiliated commercial enterprises, privileges for the military also include preferential access to markets and land earmarked for residential or other development. Senior officers serving in the army in particular, and to some extent the air force and navy as well, accumulate immense perks and privileges as they rise up the chain of command. Military personnel also receive residential plots and commercial landholdings as benefits during service, in addition to pensions and cushy corporate jobs after retirement.

As long as Pakistan’s ruling classes are unwilling to give up a portion of their state-financed privileges – tax breaks, subsidies and concessions – the government’s bloated yearly expenditures will not come down, resulting in a perennial budget deficit.

For decades, the civil-military bureaucracy and the politicians who fronted for them have passed the burden of indirect taxes on to the general public.

Truth be told, the IMF is not asking for anything radical; all it asks for is broadening the tax base and reducing the fiscal deficit. In the past, when faced with similar demands, the standard policy response by successive Pakistani governments has been to levy more indirect taxes and pass the burden onto the general public, particularly the poor and the fixed income groups.

A recent news report that shocked many Pakistanis was how the Federal Board of Revenue had unilaterally decided to purchase 155 luxury vehicles, at a cost of over Rs. 1.6 billion, out of a World Bank loan meant to upgrade its outdated information technology system. Provincial governments have placed orders for imported vehicles and even aircraft for bureaucrats and politicians. These are just a few examples in a long list of brazen expenditures that continue to divert public resources.

For decades, the civil-military bureaucracy and the politicians who fronted for them have passed the burden of indirect taxes on to the general public. This strategy is quickly approaching its expiry date, as the political cost of transferring the burden onto the citizenry has become untenable for elected governments. The current ruling coalition is worried that rising inflation will erode its political capital and limit chances in the upcoming elections. And surely it will.

The biggest recipient of state-financed privileges is the country’s corporate sector, accruing an estimated $4.7 billion per year. The second and third-biggest recipients of privileges were the country’s richest ‘one percent’ and the feudal land-owning class.

The antidotes to the current crises are well known: improving and expanding the tax system, mobilization of domestic and foreign investment which has been trapped below 15% of GDP, and fixing the energy sector that is a major source of the ballooning circular debt. Pakistan will have to focus on privatizing loss-making public sector enterprises that accumulated losses of more than Rs. 1 trillion each year. The time has also come to open up the subject of rationalizing the defense expenditure.

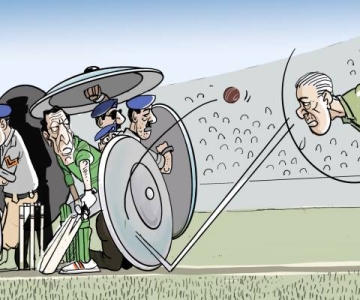

Undertaking reforms and cutting down such wasteful expenditures requires a national policy agenda that has the buy-in of all political stakeholders, including the military. Big political players – the ruling PDM alliance and former PM Imran Khan – are desperate to incarcerate and politically eliminate each other. As the 1990s remind us, such intense political conflict does not lead to stability vital for a policy consensus.

In the short-term, the ongoing intra-elite conflict is making matters worse. Given the rising inflation rates and deprivation, widespread social upheaval will be one of the inevitable consequences.