The resurgence of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and its relentless attacks on the Pakistani state come at a time when the country faces the worst economic and political crises in its recent history. During the past three months, the TTP and its affiliates have carried out more than 150 attacks, leaving hundreds dead and exposing the ill-prepared state agencies tasked with counter terrorism. An IMF delegation is in Pakistan working out the modalities of the next bailout that will temporarily rescue the sinking economy, with little or no prospect for the structural changes that are necessary to avoid an economic collapse.

The Peshawar suicide attack on Monday left more than 100 dead, and targeted a mosque frequented by police personnel. The scale of this attack is a brutal reminder of Pakistan’s own war on terror that was valiantly fought by the army, the paramilitary forces and, above all, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa police during the past decade. Unfortunately, beyond kinetic measures and army operations, no headway was made to root out the sources of militancy and extremism. In fact, policies such as the National Action Plan (NAP), National Internal Security Policy (NISP), and more recently, the security policy crafted under the Imran-Bajwa hybrid regime are all but documents gathering dust in the labyrinths of the Pakistani bureaucracy. The net impact of these policy documents is zero, because the key stakeholders were never committed to them in the first place.

What could be more cruel for the hapless Pakistani public than the celebrations that took place, albeit awkwardly, on 15th August 2021 when the Taliban captured Kabul. Former prime minister Imran Khan is on record congratulating the Afghan people and declaring that the Taliban – a violent, retrogressive force – had “broken the shackles of slavery.” Adding insult to injury, former ISI chief General (Rtd) Faiz Hameed was spotted in Kabul Serena Hotel having a cup of celebratory tea and uttering words that haven’t aged well; “don’t worry, everything will be alright.” Far from it. The flawed, bogus doctrine of “strategic depth” has completely backfired. For the much cherished and protected “strategic assets” have turned out to be liabilities, for the lack a better word. In 2023, no ‘operation’ against the militants can be successful without crossing the Durand Line and entering into an inter-state dispute. Never have Pakistan’s choices been so dire. Barely a month before the jubilations of August 2021, the military high command had actually admitted in a briefing to the Pakistani Parliament that the fiction of “good Taliban, bad Taliban” was just that: fiction, and nothing more. It seems that such proclamations could not undo the three-decade-long myopic Afghanistan policy.

Barely a month before the jubilations of August 2021, the military high command had actually admitted in a briefing to the Pakistani Parliament that the fiction of “good Taliban, bad Taliban” was just that: fiction, and nothing more.

An entire generation of officials and the general public, especially young Pakistanis, were brainwashed into lauding the Taliban as the ‘only option’ Pakistan had to maintain its influence over its western neighbour, and to counter the ‘evil’ designs of India. All evidence to the contrary, out of the box suggestions were viewed with derision and suspicion, leading to the cul-de-sac that Pakistan finds itself in.

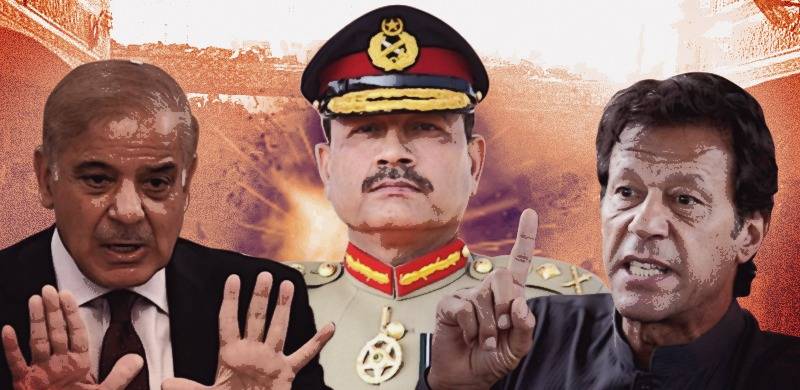

The natural order of things necessitates a policy shift, and that will happen, given the untenable status quo. But the country is deeply polarized and, with Imran Khan’s divisive politics, there is little chance of achieving a consensus on a different policy on the Taliban. Khan has his axe to grind with both the ruling coalition and the military establishment, for he considers them responsible for his ouster from office in April 2022. But he also feels empowered with public opinion on his side, and a huge social media machine at his beck and call, which has even rattled those who wield real power in Pakistan. Bringing him back on the ‘same page’ will be next to impossible without meeting his demand of early elections. Herein lies the catch: an early election does not work for either the ruling coalition or the establishment, especially given the need to restart the ventilator that is keeping the economy alive. Moreover, key allies of Pakistan are reportedly reluctant to work with Khan, and the establishment is likely to be deeply concerned about this reality. Therefore, the coming months are going to be even more divisive and uncertain, for there is no easy way out of this logjam.

Never has Pakistan needed domestic consensus over security, economic policies, and leadership that could steer the country out of the current crises.

With the appointment of a caretaker chief minister in the Punjab whom Khan considers ‘hostile’, the arrest of PTI spokesperson Fawad Chaudhry, and the mounting legal challenges for the PTI Chairman, it seems that the judicial route to contain him is on the cards. The Election Commission has already disqualified Khan, and further unfavorable verdicts appear to be in store, leading to a formal undoing of the project that was set into motion in October 2011 when the then-ISI chief actively facilitated the popular ‘mainstreaming’ of the messianic image of Imran Khan. However, this is going to be far from easy, as Khan has expanded his support base and captured the imagination of middle classes that comprise state institutions, sections of the media and intelligentsia. Today he is genuinely popular; and the economic hardship faced by working and middle classes are benefitting his cause.

There is an urgent need for a renewed charter of democracy and sooner or later Imran Khan will have to revise his inflexible posturing and do what politicians have to do: negotiate, bargain and move on.

Never has Pakistan needed domestic consensus over security, economic policies, and leadership that could steer the country out of the current crises. With a beleaguered fragile government facing public opprobrium over rising inflation due to IMF conditionality, and a disruptive Khan, the vacuum is even more acute. It is therefore imperative for the political class to rise up to this challenge. But they cannot do that without the the military taking a backseat and letting civilians take the country forward. There is an urgent need for a renewed charter of democracy, and sooner or later Imran Khan will have to revise his inflexible posturing and do what politicians have to do: negotiate, bargain and move on.

An option under consideration is the postponement of elections and an extended caretaker technocratic set up taking charge. This will only deepen the current crises leading to systemic shocks that the country and its people can ill-afford.