Izzat Majeed was raised in a household where good music was an object of reverence. His late father, Mian Abdul Majeed was an avid music fan, and from an early age his son was introduced to the finer details of sub-continental classical music. Mian Abdul Majeed was a student of Ustad Akbar Ali Khan and introduced Izzat to the layers and nuances of Indian film music that continue to guide him in his tastes and sensibilities

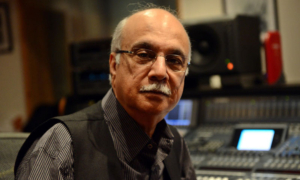

It was a mellow, moonlit evening of Lahore’s glorious spring when Sachal Studios released their album ‘Tarang’. It could not have been at a more fitting venue. Amid the decaying environs of Old Lahore stands the Haveli of Mian Yusaf Salahuddin, refurbished into a little planet of conservation as a courageous effort to protect and rejuvenate Lahore’s cultural soul. Mian Yusuf is the one denizen who has done this good deed for posterity, along with Syed Babar Ali who has conserved his ancestral Mubarak Begum Haveli in Bhaati Gate. Of course, the state has been abject in its failure to conserve Lahore’s majestic heritage.Sachal Studios is the brainchild of international businessman Izzat Majeed and man of letters Mushtaq Soofi, an exceptionally motivated duo. Sachal has infused the local music scene with innovation and energy. It is promoting a hybrid orchestra – once an integral part of the subcontinent’s film music tradition. Since 2003, Majeed, an activist and radical intellectual in a previous avatar, has devoted his time and money to this passion – to create Pakistani melodies in sync with the imperatives of contemporary musical sensibilities.

Started as a labour of love, Sachal Studios has released ‘Tarang’, a collection of music that brings together the best musicians from all over Pakistan, and Humaira Channa’s competent voice. Of late, Channa has been a victim of commercial success and the quality compromises that define Pakistan’s derelict film music. Sachal’s production is a relief; a fresh departure from the usual, and the melodic results are impressive.

At the Old Lahore Haveli, Channa with her family and associates were accorded the respect they deserve. In a similar vein, immensely talented artists, such as the tabla maestro Billoo Khan and Pakistan’s leading sitar player, Ustad Nafees Ahmed Khan also attracted the attention of the star-studded guest list and Lahore’s usual chatterati. It was on a dimly lit terrace of the Haveli that I was introduced to Izzat Majeed, who looked pleased with himself and his Sachal partners as notes from the latest album mixed with the spring air.

Inspired by the Abbey Road Studios in London, Majeed and Soofi have been working for the last six years with Christoph Bracher, a scion of a German musicians’ family, to design and set up Sachal Studios. A state of the art music studio in Lahore is a landmark, for it heralds a new trend of post-production finesse that has hitherto been missing from the Pakistani music production process. A major contribution of Majeed is his introduction of the concept of ‘music-producers’. The norms of the industry have tragically reduced the role of a producer to an investor, from that of someone who drives the quality, provides technical inputs and steers the overall aesthetic of a musical experience.

Majeed related to me how he was raised in a household where good music was an object of reverence. His late father, Mian Abdul Majeed was an avid music fan, and from an early age his son was introduced to the finer details of sub-continental classical music. His father was a student of Ustad Akbar Ali Khan and introduced Majeed to the layers and nuances of Indian film music that continue to guide him in his tastes and sensibilities.

As he reminisced about the lost eras, Majeed told me how Jazz captured his imagination in his youth. “Believe it or not, great performers such as Louis Armstrong visited Lahore, and played fabulous music at the United States Information Services office on Queen’s Road”, he recalled. But he laments the fact that the vacuum that the local music scene is trapped in is gigantic. Ustad Mehdi Hasan does not sing any more, Madame Noor Jehan is dead and the great golden voices are getting lost in the onslaught of new trends in the music industry. He conceded that the pop scene is vibrant, but a bulk of those productions are ‘pure electronic noise’. Majeed is right, because the Pakistani state has demolished, brick by brick, the secular, composite culture of the Indus Valley and replaced it with a crippling ‘ideology’ where no flowers bloom, where no bulbul sings.

This is why Sachal Studios is such an important intervention. It flies in the face of the state’s enforced desertification of culture; it seeks to encourage younger singers like Feriha Pervaiz, Ali Raza and Zaheer Abbas amongst others, to become heirs of the traditions that have historically defined musical consciousness in the popular domain. Izzat Majeed is also a poet in Punjabi and English, and so is Mushtaq Soofi. The two music aficionados have lent their verse to the myriad compositions of Sachal Studios.

Sachal’s efforts to build an orchestra have been rewarding. There is joy and unabashed triumph in Majeed’s tone when he says that in 2003 only 10 violinists were available in Lahore; the number has now increased to 30, providing extraordinary ground to the Sachal orchestra on which it can expand and deepen its range. The glorious sub-continental tradition of employing grand orchestras to enhance melodies, used by legends such as Naushad Ali, Madan Mohan, Khayyam, Shankar Jaikishen and Salil Chaudhry has become extinct except perhaps in the works of the genius, A R Rehman. In Pakistan, Majeed has picked up the tradition of serious film music of yesteryear, and has revitalised it; one hears the endangered violin instead of the plain electronic synthesiser in works produced by Sachal Studios.

But Majeed makes no grand claims. “I am not a crusader; I create music for the pleasure of music itself”, he says. This is an unusual statement in a country where bragging is a national pastime. It is easy to understand why Majeed’s partnership with Mushtaq Soofi has been fruitful. Soofi, a notable Punjabi poet, with vast experience in music production at Pakistan Television (PTV), is as self-effacing as Majeed. I met Soofi at the Sachal Studios premises, where he talked to me about his passion for music, sitting at his desk, chain-smoking, books with subjects ranging from pre-Islamic Persia to sources of the English language lying on his lacquered table. Like Majeed, he has also been immersed in music for the better part of his life. And after a long stint at PTV he has devoted his energies to Sachal. The prospect of pursuing music unencumbered by bureaucratic obstacles has set Soofi free.

Earlier, my visit to Sachal was quite an experience. Amid the ramshackle automobile workshops and Warris Road limits, which are constantly shrinking due to encroachments, stood the refurbished building, not too high yet modern in character. Like its vision, the environs and facilities of the studios were also ground-breaking. The state-of-the-art arrangements and impeccable acoustics have led to high quality results. I recalled Majeed’s words: “Pakistan has lacked embellishment in its music, and contemporary dimensions of the symphonic mode have not even been explored”. As I found out later, Majeed, like any other labourer of love is not concerned with commercial returns and profits on the music he creates.

Soofi recounted the first recording that Sachal undertook in 2003 with the celebrated composer Mian Sheheryar, entitled Saanwla (dark complexioned beloved) with kaafis of Khawaja Ghulam Farid as the highlight. A year later, Sachal released another acclaimed album called Bandish that aimed to popularise classical ragas (roughly the musical scales). Here innovations in the style of the ragas’ presentation were effected to convert complex tunes into simple geets that could be appreciated even by those who were not initiated into the rigorous discipline of Hindustani classical music. Bandish was widely noted for its rich experimentation, as it presented classical and semi-classical notes within the format of a symphony orchestra. Recently, the studio has also completed a recording of Bandish II with a wider variety of singers and composers, and the album is due for release later this year.

Two years ago, Sachal created another gem: – Lahore Ke Rang, Hari Ke Sang -, an Indo-Pakistani collaboration album. This ensemble crossed boundaries as Hariharan, South India’s most famous singer was the lead artist. Lyrics from Amir Khusro, Bulleh Shah, Hasrat Mohani, Majeed Amjad, Nasir Kazmi, and Mushtaq Soofi were used to assemble enchanting music. The album managed to collate Lahore’s liveliness and its various moods with some choice ragas and inspiring beats. The composers’ cluster that Sachal has built over the years provided the melodies for this album. This cluster included several names that are already established in the world of music: Wazir Afzal, Nazar Hussain and Qadir Shaggan among others. The music was later mastered at Abbey Road Studios, London.

‘Lahore Ke Rang’ was a huge success worldwide. Hariharan reportedly remarked on the experience in these words: “It was thoroughly enjoyable, going to Lahore, absorbing the ambience, working with such warm people and immensely loving Lahore, which is a city reminiscent of Delhi, with all its bustle and colour.”

At Yousaf Salahuddin’s Haveli, Sachal’s new work ‘Tarang’ played on, oblivious to the chattering socialites. Humaira Channa, a well-groomed artist, has rendered compositions in both classical and semi-classical modes. My favourite, and many there agreed, was ‘Dheem Tanana’ which replayed the impact of a lesser known ‘Mardang’ instrument. In fact the sound of the instrument was brought to life in this number. I was told that the guru of many a singer, the late Ustad Talib Hussain, played this instrument adroitly to enrich the rhythms of his compositions.

However, a few numbers of this album were not as powerful. Even a grand orchestral arrangement in the re-mix of Salim Raza’s song, ‘Bhool Jaao Gey Tum’, with lyrics by Tanvir Naqvi, could not mask its flatness. But the rendition of ‘Bari Thani Chahraya’ , an original by Tasawur Khanum, with a rich orchestra was a superb melody. Mian Sheheryar’s composition and poetry were elevated in this number by the ‘Boliyan’ style – essentially a folk format of dialogue through music.

Lahore’s spring breeze was soothing and as we sat on the Haveli terrace under a dark sky, the first song of ‘Tarang’, ‘Chait Charhya’ was in perfect harmony with our mood. Mushtaq Soofi’s lyrics and Ustad Nazar Hussain’s composition blended well. The month of ‘Chait’ in desi lore is the season for yearning for love. I’d like to think that there were many at Mian Yusuf’s that night who think with their hearts, and for them, this must have been a special song!

I read the cover of the CD handed to me in the dim light: “The business of music has become the music of business. To escape this, Sachal Studios has endeavoured to create sounds that make us enjoy music and not the passing commerce-driven bandwagon”. How apt, I thought, wondering how powerful the charms of music must be to have enabled these committed music- wallahs to forget about profits.

The aroma of spring flowers that adorned the jharokas and doors of the Haveli were of a piece with another number, ‘Bajariya Sey Gajrey Manga Dey’ – yearning for flower bangles from a lover. Ustad Nazar Hussain and Humaira Channa had done wonders again, supported by an outstanding sitarist. Listening to this song written by the late Hasan Rizvi, I felt as though the 70s had returned, that decade when hope was still alive in Pakistan. This song’s mood reminded me of how good our film music was in that creative decade before the film industry went into decline.

Sachal Studios are reviving an era that has disappeared – a time defined by outstanding film and non-film music between the 1950s and 1980s. In the subcontinent, music has always required patrons and patronage to survive and bloom. Since the advent of colonialism, classical music has been in decline, and the lack of cultural space in post-independence Pakistan has further endangered music forms that took seven centuries to brew and ferment. Forget classical music, we are losing the ghazal and geet variety that was once a hallmark of Pakistan across South Asia and the world. With Sachal Studios, Lahore might just find its rhythm again.

This piece was published by The Friday Times

Raza Rumi blogs at www.razarumi.com and edits Pak Tea House and Lahore Nama e-zines.