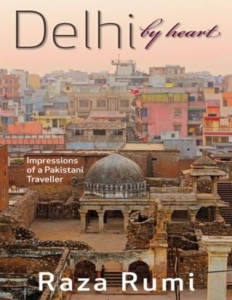

Here is a wonderful review of my book in India’s Frontline magazine

The Pakistani journalist Raza Rumi is both an insider and an outsider as he explores the trail of Sufism to the shrine of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya in Delhi.

By SHUJAAT BUKHARI

DELHI has been explored by scores of authors, both Indian and foreign. A few prominent books such as Delhi: A Novel by Khushwant Singh (1990), Delhi: Adventures in a Megacity by Sam Miller (2008) and City of Djinns by William Dalrymple (2003) immediately come to mind. Being the political nerve centre of South Asia for centuries, Delhi has always had an attraction for foreigners. Its ups and downs, too, have a unique touch of beauty and now that it symbolises the unity in diversity of the world’s largest democracy, it must surely rank high as a destination.

While we are familiar with the traditional representations of Delhi, a new book, Delhi by Heart by the Pakistani journalist Raza Rumi, is creating a stir in literary circles.

A book on Delhi by a Pakistani is intriguing, given the atmosphere of hostility has existed between India and Pakistan for over six decades now. Stereotypes have worked well to keep the citizens of the two countries apart, though until 65 years back, the people and places of India and Pakistan had a lot in common. Which is why, when one opens this 322-page book, it turns out to be exceptionally different because it not only takes a reader through the insights of someone from an enemy country but also helps us to rediscover Delhi and its glorious past.

Raza’s tryst with Delhi begins as an ordinary traveller who faces the usual suspect treatment while entering India, as is the case with any Indian who travels to Pakistan. But to his credit, he does not give up until he gains the friendship of the people in the places he visits in India. His main destination is the shrine and final abode of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya (A.D. 1243), the most revered Sufi saint of the subcontinent, as his quest is to discover more about the throne of Sufism in Delhi. It is this quest that has shaped his random thoughts and plans for his ambitious journey into a book. The flow is natural and the thought processes pull a reader in.

He takes help from his acquaintances and friends to unravel the intricate philosophy of Sufism, which has of late been thrown up as an alternative to Islamist extremism. But he does not confine himself to this quest; he explores the cuisine, social engagements and to some extent other areas in Delhi that have gone through a radical change. He takes us beautifully through the old and rather unkempt narrow lanes that have unfortunately become the symbol of Muslim identity in Delhi. But he does not go into the reasons for the backwardness of these areas.

Women of substance

The author is attracted to the personalities of Hazrat Nizamuddin, Amir Khusrau, Sarmad, Dara Shikoh, Zafar, and Mirza Ghalib and he talks at length about their journeys and endeavours. At the same time, he also devotes a significant part of the book to prominent women of the time. Razia Sultan, the first woman emperor of India, gets a lot of attention in the book. So does Jahanara, who stood with her father and wronged brother against Aurangzeb, and Zebunnisa, Aurangzeb’s daughter, who took her own decision to move on, rebelling against her father.

The remarkable work done by these women in the areas of social service, arts and mysticism is explored in detail in the book. By paying tribute to these women of substance, Raza is also trying to show that the Indo-Muslim culture was not necessarily male-dominated.

Having been brought up in Lahore, a city that maintains its links with Delhi even today, Raza connects with the culture and social moorings that these two cities share. Despite the many ups and downs that both the cities have witnessed in the past, they owe their uniqueness to the shared architecture gifted to them by the Mughals. He unravels the many layers of the city and successfully reconnects the richness of the Urdu language with mystic Islam and the unavoidable link it has established with Hindustani classical music. The ways in which Bollywood has benefited from this richness have surely something to do with the magnificent past of Delhi, which was once one of the two important centres of Urdu.

What makes the book a good read is that Raza connects the past with the present and makes his own inquiries into the city through vibrant conversations, anecdotes, lessons of history and the contribution made by great people.

He is not a disappointed other, but does his job as an honest writer and journalist to put Delhi in perspective. Even as Mir Taqi Mir, the great Urdu poet, who, in a way, symbolises the existence of Delhi, is disappointed at the city being desolate and barren, this brilliant work gives us hope.