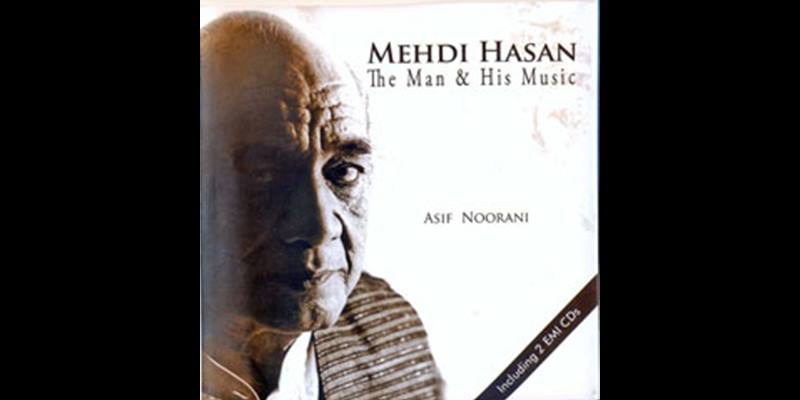

The Man & His Music

Asif Noorani

Liberty Books

Karachi (Pakistan) 2010

Pg 80

Rs 695

Amit Sengupta Delhi

This is a collection of tributes. There is a certain profound admiration for a man with a magical voice weaving lyrics and music which these days can only remain in the realm of a mythical, classical, velvet fantasy. Journalist Asif Noorani from Karachi, has painstakingly collected and edited this neat volume with lovely black and white archival pictures. An eclectic group of writers have penned pithy, innocent revelations on Mehdi Hasan, without heavy pretensions or flowery language, often with a nuanced personal intimacy which transcends the ‘glossy brochure eulogies’ of cross-border legends in the sub-continent – still nursing pre-Partition nostalgia, fragmented, fading memories, and deep, embryonic, unrequited cultural longings.

There is pain and nostalgia which stokes the dark corridors of time after Partition. Mehdi Hasan was born in 1927 in Luna village in Rajasthan. His father, Ustad Azeem Khan, was his mentor; he was also tutored by his uncle Ustad Ismail Khan. Still a teenager, Partition brought tragedies and bloodshed. For him, hardships. He worked as a bicycle and motor mechanic.

Writes broadcaster Raza Ali Abidi: “Come Partition and he migrated to Pakistan with his family in difficult circumstances. …in the early days of the new country classical music had gone into wilderness. No one understood music, let alone appreciate it… In order to make a living he became a motor mechanic… Later he opened his own garage, which kept him so busy that he just couldn’t sing for four years – from 1948 to 1951. However, he did his riyaz (music practice) regularly. He claimed in his interview with me that in Bahawalpur state he had repaired and assembled about 300 to 400 diesel engines. He was not shy of his foray into what many would consider a menial job.”

As a budding singer on radio and stage he initially sang Talat Mahmood’s songs. Two offers to sing in Karachi arrived with bad luck in 1956: the movies bombed. Six years later, he marked an elevated rupture with Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s ghazal, ‘Gulon mein rung bhare’, recorded at the Lahore studios of the Gramophone Company of Pakistan (later EMI).

Indeed, as music archivist Sultan Arshad says, from mid-1960s to late 1970s the best ghazals and romantic songs recorded for Pakistani movies were the ones sung by Mehdi Hasan. But he never quite reconciled with the invasion of pop music, nor succeeded with light numbers. “Hasan’s innings as a playback singer came to an end after he recorded a song composed by Kamal Ahmed for Jeene Do (1995), but the last time the great singer faced the microphone was when he recorded Allama Iqbal’s poem Masjid-e-Qurtaba, composed by old timer Nisar Bazmi. That, sadly, turned out to be Bazmi’s last recording as well.”

As this book was being compiled last year, illness and fragility came to torment Hasan. The legend seemed to be becoming a forgotten note. Ailing seriously, with regular speech therapy and physiotherapy, the right side of his body had been badly affected. He was stalked by financial crisis. Writes Asif Noorani, “He looks tired, very tired, as his wheelchair is pushed into the room at the Aga Khan Hospital, Karachi…”

Murmurs Hasan, “Imagine, all this happening to me in my twilight years…” He asks for a cigarette, the request is declined politely. He settles for a paan…

The ghazal singer was always innovative because he was a trained classical musician. Says Nayyara Noor, as she sings the first line of Mir Taqi Mir’s famous ghazal, ‘Patta patta boota boota’:“There is no exponent of ghazals who can add so many nuances to ghazal singing… Believe me, it’s so difficult to render it and yet Mehdi sahib does it so effortlessly…”

Writes Raza Rumi, senior journalist based in Lahore: “Mehdi’s Hasan’s richness of expression and superb career is a matter of pride for us… I remember my childhood when radio, television, cinema and mehfils were nothing but revered spaces devoted to Khan sahib… However what did the State do? A mammoth entity inhabited by vested interests and anti-culture elements, the State initially showed minimal interest in the treatment of Mehdi Hasan’s prolonged illness to the extent of being cruel… But this has been our tragic tradition. Our greatest artists, singers, poets and intellectuals have suffered at the hands of a conformist society and State captured by puritans, especially since the late 1970s… It is never too late for the intelligentsia of this country to mobilise public pressure on the State machinery so that it learns to respect cultural diversity and the imperative to nurture a creative, healthy and civilised society…”

The music collection that accompanies the book contains many of the magical renditions: Ahmad Faraz’s ‘Shola tha jal bujha hoon’ based on Raga Kirwani, ‘Gulon mein rung bhare’ (Faiz is reported to have said, “Woh ghazal to ab Mehdi Hasan ki ho gai hai.”), Mir Taqi Mir’s ‘Ye dhuan sa kahan se uthta hain‘, ‘Chiraage-e-toor jalao bada andhera hai’ by Sagar Siddiqi, ‘Pyar bhare do sharmeelay nain’, ‘Tere bheege badan ki khushboo se’ and ‘Mujhe dil se na bhulana’. The CDs also feature three Radio Pakistan recordings of the 1960s, a Bulleh Shah Kafi, an Urdu translation of Heer, and athumri in Tilak Kamod, ‘Dukhwa mein kaise kahoon mori sajani’. Plus, the exquisite rendition of ‘Kesarya baalma’, a folk tune from Hasan’s native origins, the barren deserts of Rajasthan where bright colours bloom.

Mehdi Hasan’s five favourites, even while he seems inaudible in the hospital: ‘Zindagi mein to sabhi pyar kiya karte hain’, ‘Gulon mein rung bhare’, ‘Too ne ye phool jo zulphon mein chupa rakha hai’, ‘Mujhe tum nazar se gira to rahe ho’, and ‘Pyar bhare do sharmeelay nain’…