Pakistan has crossed a major milestone last week by achieving a historic consensus on the 18th Amendment with 105 clauses, additions and deletions to the Constitution. The distortions inserted by the military rule have been done away with. Political elites this time, however, have gone a step further and improved the state of provincial autonomy. Perhaps this is where a civilian negotiation and democratic politics of compromise has been most effective. Who would have thought a few years ago that this was achievable? There were many skeptics who thought that the amendments might not be approved. However, the ‘corrupt’ and ‘incompetent’ politicians have proved everyone wrong.

Leaving aside the discourse of corruption, the NRO, and a vociferous media campaign against the President, the achievements in the last one-year by all political parties have been tremendous. The Awami National Party, after its initial truce with the militants, has stayed the course and resisted Talibanisation by giving full support to the army operations against the militants. The PPP and PML-N, despite their rhetoric and political point-scoring, have worked together on the national finance commission award (NFC) and now on the implementation of the Charter of Democracy (CoD) that has become the basis for the amendments to become a reality.

The nay-sayers of democracy and the political process forget one fundamental fact: a federal structure cannot work without a robust political process. A start has been made through the recent successes after a decade of ‘controlled democracy’. However, despite the march towards the democratic ideal, there are clear and present dangers that democracy is as fragile as ever.

The reasons are not difficult to state: the political class that is adept at wrangling and the unelected institutions of the state whose quest for power is an ever-present reality. The second factor is the dwindling state of the economy that shows little or faint signs of recovery. This would spell disaster for any civilian government regardless of which party is enjoying power at the centre. Finally, the transition required at the federal and provincial levels of governance will also be a challenge bringing out the issues of state capacity into the limelight.

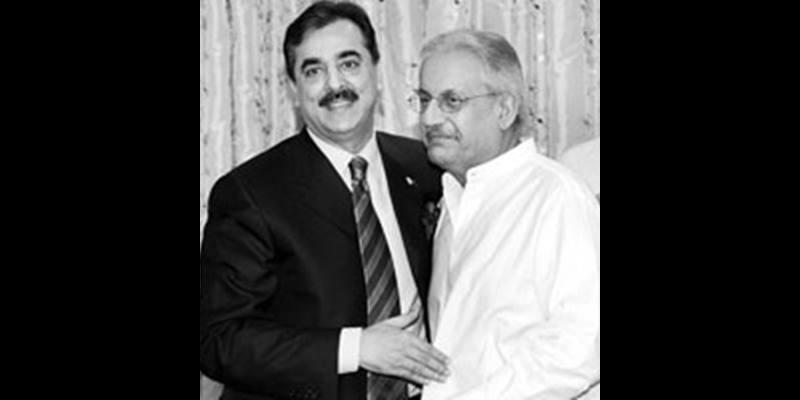

Some credit should go to the otherwise-discredited president. Mr Zardari has relinquished powers to appoint or sack prime ministers, service chiefs and judges. He has agreed to the abolition of limits restricting prime ministers to two terms, clearing the way for Nawaz Sharif, the opposition leader, to become prime minister yet again. And he has given the chief justice a veto over the appointment of fellow judges.

Political elites

There is no denying that history has been made. It is rare to find a politician who gives up powers of his own accord. The incumbent President who had no credibility to begin with, thanks to years of witch-hunts, media trials, and transgressions has proved all his critics wrong. His role and powers have been reduced to that of a figurehead.

But the relentless campaign against him continues unabated. This does not augur well for the future of democratic process. It is a truism that no political party wants a general election. The public position of the parties is clear on that front. Yet, the mounting campaign against the President who happens to be the leader of the largest political party implies that the consequences of his exit from the office stripped of all powers will lead to further instability. An in-house change that comes out of exigencies of power politics will also set a wrong precedent that the two main parties have worked to avoid at all costs.

Unelected institutions

The key power wielders in Pakistan are now the two institutions of the state, the army and the judiciary. The latter has acquired power on the basis of a populist movement and its decisions thus far have taken cognizance of public mood. Whether it was to set the price of sugar to the reopening of the Swiss cases against the President, there seems to a clear tilt towards the popular as opposed to the technically legal.

The army has also recovered from the setbacks caused by the Musharraf era. First, it has shown great resolve against the militants in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and the FATA and has earned public approval. In addition, the belligerence of Indian leadership has also made the army central to debate on Pakistan’s survival. Most importantly, the West, especially the USA, has also formally recognised the army as the counterpart negotiator. The latter views Pakistan army as central to its Afghanistan strategy even at the expense of the full authority of the civilian government.

Several analysts, however, maintain that the swing of the power pendulum towards the army and the judiciary is a danger to the future of civilian governance, which was achieved after prolonged struggles on the Pakistani streets.

A particular matter of concern is the issue of presidential immunity, which has been brought into public light through the judgments of the Supreme Court. Whereas Article 248 of the Constitution is quite unambiguous on this issue, there are strong indications that the court is in a mood to reinterpret the article and submit the judicial process to a populist clamouring for accountability and anti-corruption.

Policy initiatives over the last year have shifted from the federal cabinet and the parliament to the GHQ and the courts. Whether it is policy regarding India, war against terrorism, prices of essential commodities, promotions within the civil service or appointments of judges, the elected government has a very limited role to play and has had no choice but to submit to the decisions of the two powerful institutions of the state.

State capacity

The 18th Amendment calls for a major shifting of powers and functions from the centre to the provincial governments. Questions have already been raised on the limited capacity of the provincial governments to adjust to newer realities and whether they are prepared to assume enhanced responsibilities – from regulatory mechanisms to policy-making, curriculum-development or even legislation. What will happen to the mammoth federal bureaucracy and how would it manoeuvre to preserve its vested interest is a question to be reckoned with. In addition, the provincial governments have already rolled back the comprehensive local government reform initiated by General Musharraf, leaving a huge governance vacuum at the local level. Rights, entitlements and services are mediated and negotiated at the lowest level of governance. The citizenry is soon going to find it pushed to a corner when the local state is in a process of transition, while the provincial government is too busy acquiring and consolidating newfound powers. In the short-term, there is going to be administrative chaos, if not anarchy at all four provincial capitals. If we add the usual power struggles between the centre and the provinces, this process is going to be messy and, dare one say, conflictual.

Missing amendments

As noted above, the political consensus achieved thus far is phenomenal by all accounts. However, the reforms committee and the parliament have ignored two issues. First, the status of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) has been left untouched. What were the reasons for not addressing this war zone and global hotspot by the maverick political elites of Pakistan? If they were scared of the national security apparatus, they could have engaged with the GHQ, as they generally do at the drop of a hat. Second, the Islamic provisions unlawfully inserted by General Ziaul Haq are very much there, keeping Zia’s ghost alive and kicking, even though his name has been deleted from the basic document. For instance, the condition of the Prime Minister being a Muslim is completely unjustifiable. Given that Pakistan is a Muslim-majority country, why should such a provision be retained in the basic governance document? This is just a simple case of pandering to the mullah lobby and the process since 1948 remains unchanged.

The ailing economy

The larger issue remains: how will the improved constitutional structure lead to economic progress, more jobs and opportunities for the millions living below or a little above the poverty line? The growth rate is struggling to increase a little over the population increase per annum. The 25 percent inflation rate is the highest ever witnessed by Pakistanis: and all estimates and forecasts suggest that the prices of food are going to further increase. The ongoing energy crisis has depleted what little industrial capacity there was, and the political squabbling over the type of power plants means that any solution to this crisis would be controversial and used for political gains. This is perhaps an area where the political elites need to reconvene and think beyond their immediate power-interests. Pakistan is in a desperate need for structural reform. Only 2 percent of the population pays taxes and there is little or no collection under the head of agricultural income tax. Similarly, the economic policy-making process is completely in the hand of the international financial institutions and generalist bureaucrats at the top. Unless the major political parties agree on an economic reform agenda and fully implement it, we will remain a debt-trapped, cash-starved and failing economy. The current signs are not promising: there is deep suspicion about the economic management at the centre and there is a lack of bipartisan consensus. In this situation, the democratic experiment reignited in 2008 faces a major challenge. Perhaps this is the biggest threat to the survival of democracy in the country. The fundamental cause of the lack of economic performance is political instability that may not go away so easily. Therefore, another reforms commission is required to deliberate and come up with a package that includes protection of citizen rights and confronting the economic oligarchies by strengthening the competition commission of Pakistan.

In conclusion, we have come a long way from the dark years of military dictatorship but we are still not poised to enjoy political stability, democratic governance and economic progress. Geo-strategic compulsions, over-powerful institutions of the state and dismal economic conditions may just dilute the effect of the recent constitutional amendment passed by the Parliament. Finally, state capacity to deliver on all these fronts is weak and under severe challenges, and it is time the Raza Rabbani committee is followed by several commissions to implement the reform in the political and economic domains. Otherwise, we will continue to be trapped in the cursed cycle of history.