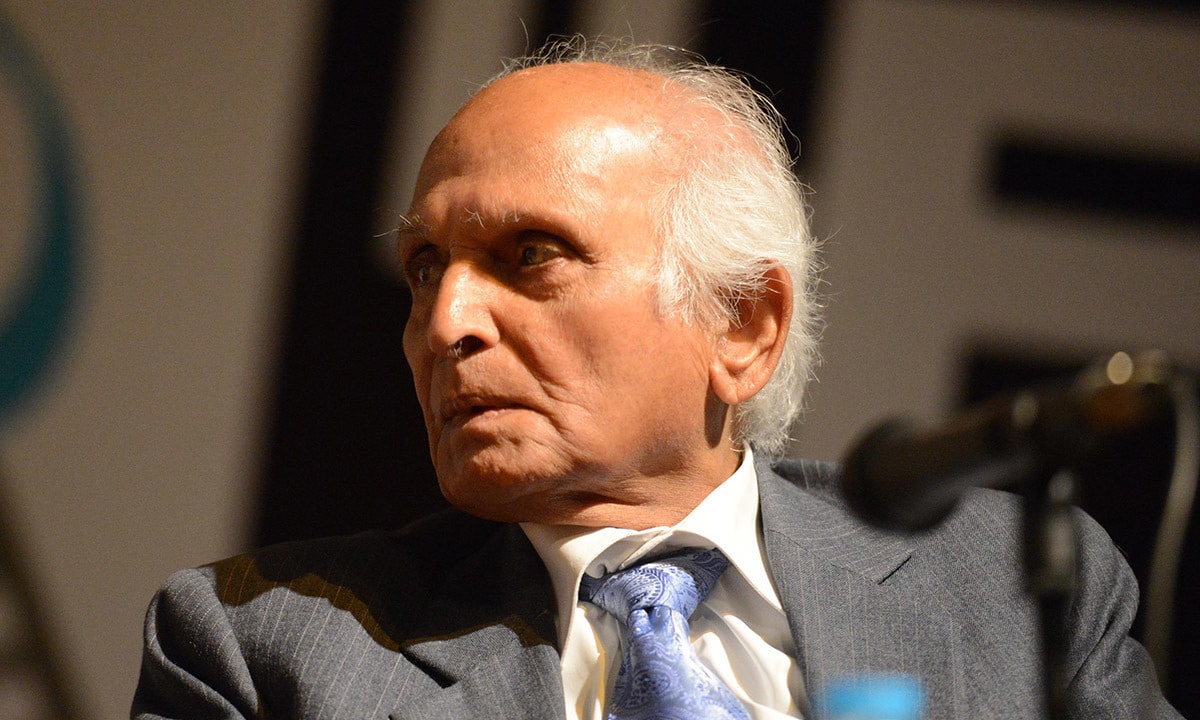

Intizar Hussain’s nomination for the Man Booker International Prize has finally placed him on the map of global literature, something that should have happened long ago. Intizar Sahab is Pakistan’s foremost Urdu prose writer who has retained his excellence in storytelling for decades and has also evolved in the milieu that Pakistan, the country of his choice, provided him.

There are many sides to Hussain: storyteller, journalist, public intellectual and mentor to many a writer. His wide-ranging oeuvre – novels and short stories, columns and memoirs – chronicles the unresolved questions of identity, location and migration. Hussain’s novel ‘Basti‘, epitomizes the conflicts and contradictions of human existence that Intizar Hussain has pursued throughout his long literary career.

Once I asked Intizar Sahab about his experience and, in his typically innocent manner, he said that despite his physical dislocation he never imagined this Hijrat was going to be a permanent separation. In fact, until the 1965 war there was considerable traffic between India and Pakistan. So what was initially a period of trauma and discomfort turned into a permanent state of dislocation.

In the early years of Pakistan, Hussain took the nationalistic line and shared the optimism that was the rage among one school of thought within the small literary community of independent Pakistan. Hussain’s major influence at this time was Muhammad Hasan Askari, the writer and critic who took many ideological somersaults in his long career. Hussain was influenced by Askari to the extent that he found himself on the other side of the ideological divide from the Progressive Writers’ Movement. The latter were more circumspect and cynically cautious about the trajectory of the new Pakistani state. From the 1950s Hussain therefore was bracketed with the rijat pasand (regressive/conservative) writers. This continued until 1971, when Pakistan suffered another trauma in the form of Bangladesh’s secession. The upheavals caused by that event which could neither be admitted nor lamented in public by most West Pakistanis. To publicly admit the Pakistan Army’s assault on East Pakistan would have undermined Pakistani nationalism, after all, or the very ethos of a separate state created in the name of Islam; and its denial was a direct threat to the humanistic vision that was adhered to by most writers and intellectuals. The modernists and progressives never left an opportunity to berate Hussain for his conservative political ideology. However, even his harshest critics conceded his extraordinary storytelling skills and the musical earthiness of his writing, whether he was evoking the shade of the tamarind trees in his native UP or the cosmopolitan mahaul of Lahore’s Mall Road in the 1950s.

The truth is that Hussain didn’t take a clear ideological line in his early career. Instead the characters in his short stories, often migrants or people related to those unique creatures, were haunted by memories and nostalgia. The universe comprised the crude realities of their new homes and environs and a very interiorized process of making sense of existence as a whole. For example, the 1951 story ‘Ek Bin Likhi Razmiya‘ (‘An Unwritten Epic’) brings together various attitudes to the Partition and also shows the debasement of its epic hero who pursues the manipulative allotment of a flour mill in the new state. Intizar’s writings from the 1960s onwards, such as ‘Aakhri Aadmi’ (1967) and later ‘Shehr e Afsos‘ (1973), are darker and more political. The latter collection of short stories has direct references to the excesses committed against Bengalis in 1971.

And then came ‘Basti‘ (1979), which was now been translated by Columbia academic Frances Pritchett. It is a culmination of two decades of Hussain’s experiences as a writer, a migrant and a Pakistani. Zakir, the protagonist of ‘Basti‘, is like Hussain a resident of Rupnagar. He is like the younger Intizar; he moves to Lahore and like the writer embraces the past and present with uncanny ease. Zakir has Karbala and Sravasti on his mind; the pathos he comes to feel in his adopted city, woven as it is through the migrations of centuries, creates a delicate work of art which inspires empathy in readers.

‘Basti‘ also marks a turning point in the history of the Pakistani novel. Until then the big Urdu novels of the time were being authored by Qurratulain Hyder from India. (Interestingly, Hyder was invoking the similarly lost idylls of Lucknow and Dehra Dun.) Hyder once accused Hussain of “selling” migration as a theme in his literary output. She herself had migrated twice from India to Pakistan and once again back to India. The second migration sort of settled her but gave her a new challenge of adjusting in a democratic India where Urdu was declining and a new post-colonial culture was taking shape.

Hussain’s later works ‘Tazkirah’ (1987) and ‘Agey Samundar Hai’ (1995) record the contemporary conditions of a truncated and changed Pakistan. Formally, we find in these works an increased emphasis on mythology and symbolism, an attempt by Hussain to link his world to that of the ancients.

During General Zia’s long dictatorship many writers were forced to adopt metaphors, as the freedom to write openly about repression was limited. Hussain’s style merged with the trends of that era. His contemporary and critic Enver Sajjad wrote his famous ‘Khushion ka Baagh’ during this time – an allegory that records the anguish and turbulence of that era. Hussain’s later stories are replete with symbols from Hindu mythology as well as other cultures, which make him a torchbearer of peculiar civilizational continuities.

And we haven’t even come to Intizar Saheb’s autobiography ‘Justuju Kya Hai?’ (2011). The book is about his early influences and experiences in writing, particularly journalism. Hussain’s columns have not been extensively analyzed but they are great samples of taut and creative journalism. His journalistic style has not impacted his fiction and he has the rare distinction of keeping them as far apart as two parts of one person can be.

It is an irony of our times that Hussain is now among the leading progressives of Pakistan. His moderate and enlightened invocation of the Indian subcontinent’s ancient pluralism and tolerance makes him a foremost voice of moderation. His columns articulate a vision that is blurred in our highly sectarian, myopic and fragmented Pakistan. His fiction concurrently reminds us of our shared past with regional civilizations and, more importantly, our common regional heritage. Now, near the twilight of his career, Hussain’s canvas presents a universalism that stares unblinkingly into the face of jingoistic Indians and Pakistanis.